In this conversation, Cuban-American interdisciplinary artist and writer Coco Fusco talks about her new book Dangerous Moves: Performance and Politics in Cuba (2015), which analyzes performance art and political engagement in post-revolutionary Cuba. Fusco discusses how performance art can be defined; why performance art has long been marginalized in Cuban society; and how the specific history of performance art in Cuba might resonate with other schools of performance or regions in which performance has been enacted today.

Stephanie Bailey: Your new book Dangerous Moves: Performance and Politics in Cuba (2015) explores how performance has been the most important medium for challenging state control of the arts and testing the limits of public expression in Cuban civil society. I wonder if you could talk about how you came to produce this book and what intentions you had when devising it?

Coco Fusco: My relationship with the Cuban art community in Havana began in the 1980s when I first traveled to the island upon being originally invited by Flavio Garciandia, Ricardo Rodriguez Brey, and José Bedia. I was very interested in the art scene and in the aesthetic and political vision of these artists who wanted to transform their culture and broaden the expressive possibilities of art. I have followed the art scene over three decades and witnessed many stages of its evolution. The artists of the 1980s generation are widely considered to have transformed the visual arts landscape in Cuba after a period in the 1970s in which social realism prevailed. The 1980s is considered the beginning of the visual arts renaissance. In the early 1990s, a wave of censorship and the end of Soviet financial aid to Cuba led to an economic decline – these were the principal factors that led to a shift towards more formalist object-oriented art making. Work from the 1990s was not so confrontational in content or method. In more recent years a steady stream of young Cuban artists, whose practices combine conceptual sophistication, minimal means, and a touch of localism in content, circulates in international exhibiting arenas.

On the island, the range of art practices is more varied, but the edgier, more politically-oriented and less marketable work takes place outside of official state venues. When I was nominated for the Absolut Award in 2013 and had to turn in a proposal for a book that I could complete in a year, I knew that I had to write about Cuban art because I care about it and also because I had already done enough research to be able to start writing quickly. I felt that performance was an important field that had not been given enough attention, so I decided to concentrate on that medium.

SB: In your preface, you note that performance practices in Cuba exist outside the realm of fine art and “receive little attention from the country’s cultural apparatus and from international art critics.” Why do you think that is?

CF: Performance art in Cuba is not easily marketable and has often been considered politically controversial, hence it is not promoted as much as painting, photography, installation, and sculpture.

SB: So the project of Dangerous Moves is to construct a history that had not yet been historicized?

CF: Yes. I note in the book that the political project, implicit and explicit in much performance produced as art, had also not been addressed.

SB: Why is that? This is, of course, a global question given the fact that so much focus has been placed on performance, particularly in museological contexts, in the last decades.

CF: The reasons for the marginalization of performance in the Cuban context is not exactly the same as why the performance was not taken up by museums in the USA or in Europe. Contemporary art’s absorption into museums is a relatively recent development. In the 1960s and 70s, little contemporary art of any kind was shown or bought by museums. The performance was something done by experimental artists who had little relationship to the art market. It was not until the 1990s that art museums started to deal with non-traditional forms in a more systematic way, in part because there was not much more modern art left to buy and also because new generations of art historians and curators have focused their research on the contemporary. I would also argue that the acceptability of non-object art forms like performance relates to a general social context in which information and packaged “experience” become valuable to the global economy. People are willing to buy experience and go to museums to have experiences these days.

In the Cuban context, performance is not only marginalized because it is not marketable but also because it is considered volatile and politically dangerous. Unlike stable materialized forms that can be seen and approved prior to the exhibition, performance is usually invisible and unpredictable.

SB: How would you define performance art today? And when looking at performance in Cuba, what criteria did you apply?

CF: I don’t have my own definition of performance art. Artists working in performance get to do or not do almost anything and call it performance. As long as artists claim events, actions, and lived conditions as performance and audiences accept the proposition, performance art “happens.”

In the book, I look at performance across a range of sites: art, activism, music, religion, tourism, and official mandated civic engagement. That broader purview allows me to make the connections between performance art and politics more clear. That method corresponds to the way that performativity (not performance art) is treated in performance studies (rather than art history). Performance studies is concerned with the study of performance across a range of fields and social practices, from sports and rituals to legal procedures and political activism. The field draws on methodologies from the study of theatre, anthropology, literary theory, and legal studies.

I look at the relationship between performance and politics. Some of the performance I treat is not conceived of as art – it is understood as a religious practice, civic engagement, or activism. Some of the performance art I deal with in the book draws on social codes of conduct and body language that comes from the political arena or the practices of religion, so having a methodology that allows me to analyze performance in and outside of art is very useful.

SB: In the book, you outline two dominant views in the literature for interpreting performance art in Cuba. The first line is “largely anthropological and focuses on the vernacular performativity that abounds in Cuban popular culture in street carnivals, cabaret culture, and syncretic religious processions. Artists working in this vein are understood as ‘engaging in quasi-anthropological studies of vernacular Cuban cultures, appropriating and refining their aesthetic elements to produce works that allude to folklore without being folkloric,’ with an interest ‘generally understood to be restorative, part of a longer history of vindicating the cultural practices of formerly marginalized social groups in Cuba.”

The other line relates to Cuban art pedagogy and avant-garde practices, the first wave of which emerged in Cuba in the 1970s and early 1980s, when many artists of the Cuban art renaissance drawn to performance became professors at Havana’s University of the Arts and “quickly incorporated the practical, historical and theoretical study of performance into the curriculum,” such as René Francisco, Lázaro Saavedra and Ruslán Torres, who formed art collectives with their students in the 1990s such as Galería DUPP (Desde una pedagogía pragmatica – From a Practical Pedagogy), Enema and DIP (Departamento de intevenciones públicas – the Department of Public Interventions), in which “performance became a central means of creative expression and sociological exploration.”

How did you position the narrative of Dangerous Moves in relation to these two trajectories?

CF: I was trying to delineate another line of inquiry, one that focuses on the relationship between performance and politics and that accounts for artists who have used performance to make political statements, who treat political conduct and political rhetoric and sculptural material, and activists whose tactics are self-consciously dramatic.

SB: Could you talk about the process of researching Dangerous Moves; were there any specific practices that acted as starting points or lynchpins for your research into performance art in Cuba?

CF: In the book, I draw on a variety of methods of research. I have visited exhibitions of Cuban art in Cuba, the USA, Mexico, Brazil, and Europe. For example, I have been to various Havana Biennials, national salons, visited state-run galleries and attended public presentations at the University of the Arts. I have visited numerous artists’ studios for 30 years, visiting artists during every trip to Cuba and also visiting Cuban artists in Miami, New York, Spain, and Mexico. I have also attended many events at independent galleries – some provisional and some ongoing – in Cuba in artists’ homes. I have an extensive collection of writings on Cuban art in English and Spanish. I also follow Cuban blogs and YouTube channels where artists and musicians and activists post their videos. As I was developing the argument in my book, I interviewed several artists about their works as well. I did also consult some scholars who work on contemporary Cuban culture. The organizational structure emerged from the interviews.

SB: What were the challenges in producing a publication that pays homage to an entire genre in Cuban art history, and the processes through which you brought your material together into the final form of the book?

CF: The main challenge was time and space. The Absolut Art Award stipulates that I must turn in a manuscript in one year. The publishing contract limited the amount I could write about the subject. I had to figure out a way to make a coherent argument within those restrictions. Fortunately, performance doesn’t have such a long history in Cuba. I could not have written about the entire genre of painting, for example, within the framework that was set out for me by the award. But I also did not write about the entire genre of performance – I focused on performances that engage with political issues and state power.

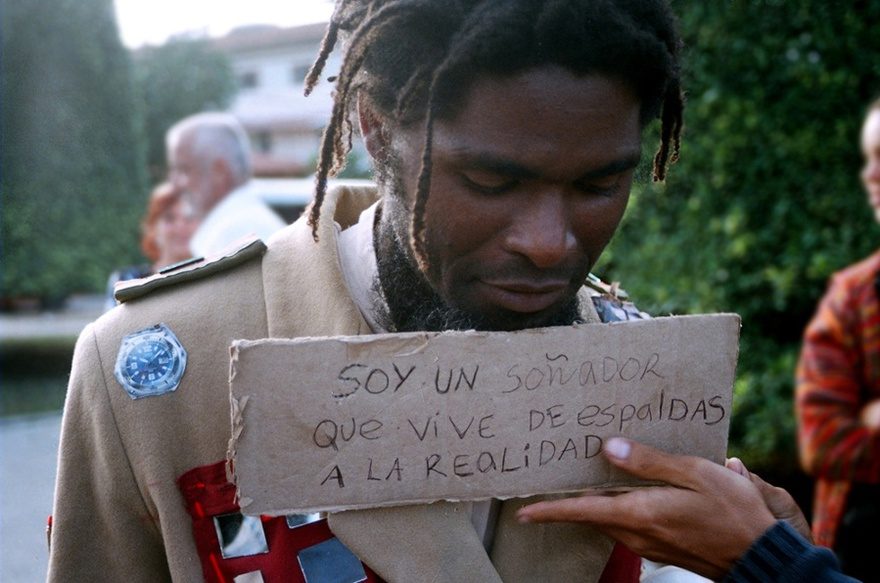

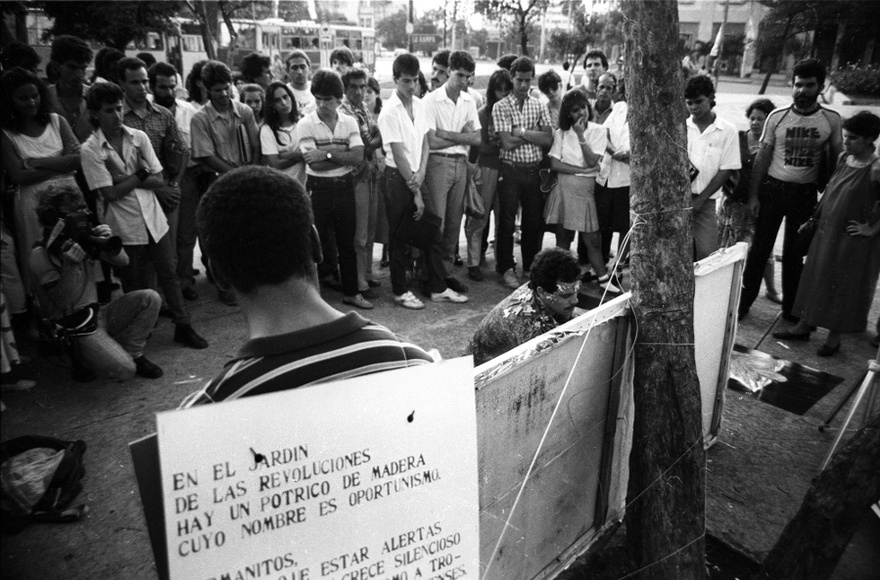

I start my book with a reading of an infamous performance by Angel Delgado in 1990 in which he defecated on a Communist Party newspaper. Although his performance took place in a gallery at an opening it was unsolicited. He was imprisoned for six months. In the second chapter, I take a close look at several works that deal with surveillance and policing in Cuba using different strategies: works by the Department of Public Interventions (DIP Collective), Humberto Diaz, Yeny Casanueva and Alejandro González, and musician Gorki Aguila. I also discuss the case of Juan Sí González, the first Cuban artist from the 1980s who sought to take art to the streets of Havana, creating events that were unauthorized and very loosely scripted encounters. I see him as the first practitioner of relational aesthetics in Cuba.

SB: In terms of producing a history of performance art in Cuba, you mention the fact that performance is “the art form that most consistently engages in, and reflects upon, the social construction of the body and the codes of public conduct, [and] offers a more complex treatment of the politics of movement in Cuban public space.” Your intention, you write, is to consider “the dynamic relationship between corporeal expression and state authority in light of Michel Foucault’s notion of biopower.” To this end, how might Dangerous Moves, while exploring a very specific history, resonate with other schools of performance, or regions in which performance has been enacted today?

CF: I think there are parallels that could be drawn to the situation of artists in other countries in which culture is managed by a centralized state apparatus. I am thinking here of the situation in post-war eastern Europe before the fall of the Berlin Wall and also in China.

SB: Could you elaborate on this?

CF: I don’t think I can answer your question without writing another book! I am also not an expert on the art of the regions either. The issue is just too complicated. Suffice it to say for now that artists working in eastern Europe before the collapse of state socialism were dealing with similar political contexts and similarly centralized state authority in the realm of culture. In the case of China, there were many artists in the 1980s who used performance to critique state power, to call for liberalization, and also to comment on the emergence of capitalist economic practices.

SB: Taking into account the fact that your practice has been described as one that examines “the relationship between the abject body in performance and the greater body politic of a state,” I wonder if you might comment on the wider observations you have made in this study to the relationship between the performing body and the state when it comes to thinking about your practice as a whole?

CF: Having had an ongoing dialogue with Cuban artists over 30 years has definitely informed my practice, but not just my performances – these conversations have helped me to understand my cultural identity and my creative endeavor. I learned a lot about state power, about how artists negotiate with power, about how art forms that don’t appear to be political can be read politically, and how artists understand what they do. Cuban artists are astute observers of their social reality and they are not idealists. I have always found their critical perspectives to be more sophisticated than that of most American artists. The conversation about politics and art in the USA is limited and naive. It’s all about an abstract idea of freedom or about how bad political art is, or about how art is supposed to change the world in a New York minute. So I listened and learned from the Cubans.

SB: Could you give an example that might illustrate this difference between political art in the USA and in Cuba?

CF: I don’t want to be reductive here. It is not as if there is one way to make political art here or there, and there is no one artist that represents the American or the Cuban way of making art or dealing with politics. I also don’t want to privilege one artist over others – that is what the art press in the USA constantly tries to do and I don’t agree with that approach at all. For me, the important difference is that Cubans are socialized in a highly politicized culture and in an economically fragile country in which they represent an elite. One of the results of that condition is that their ability to analyze cultural politics and the workings of state power is more refined and more sophisticated. They operate with a sense of realpolitik that many Americans lack. Americans’ cultural isolation, economic privilege, and naive belief in their “freedom” as artists and as citizens of the so-called free world makes it much harder to engage in analysis of cultural politics.

SB: To this end, what might artists and scholars from other regions learn from Cuban performance art histories?

CF: That really depends on what one is looking for. There has been a good deal of performance scholarship about experimental artists in Latin America from the 1970s that responded to state repression: artists who used the mail systems to circumvent the control of the circulation of their work and artists who took their work to the streets to comment on state violence and so on. The focus of that scholarship is largely on artists who worked in military dictatorships that existed in Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, and Brazil. Cuba represents a different scenario, a different political culture, and one that purports to be leftist and revolutionary. However, Cuba shares some of the characteristics of right-wing dictatorships – there is an authoritarian state that polices public space and public behavior; power over culture is centralized, and access to foreign influence through media and culture is also tightly controlled. Perhaps the case study of Cuba is useful for those who are looking at culture in other third world nationalist states with similar forms of governance.

SB: In the book, there is a prevailing sense of tension in the performances you describe: a sense of boundaries being mediated, inhabited, or challenged – as in The Drama of Becoming Another: Paranoia by DIP in 2002. The project was staged on Obispo Street is a long pedestrian walkway in Old Havana to “determine what subjective and objective responses might be triggered by producing a semblance of suspicious activity.” The artists passed an aluminum briefcase between each other at 30-minute intervals as they walked down the street, insinuating an illicit exchange. Though the project did not provoke a reaction, you quote one of the participants, María Victoria Portelles, who describes “an extreme paranoia in the minds of the performers, who feared that the police might read their feigned illicit activity as true criminality.” Public statements about the work claim that it “sought to induce the heightened emotional state that ‘we experience when we internalize the apparatus of power.'”

This reminded me so much of Sondos Shabayek’s recent essay for Ibraaz on the issue of censorship and self-censorship in relation to the BuSSy Project in Egypt, of which she is a director, which touches on the way performance art places real bodies in dialogue with structures of state power. I wonder if you might comment on the relationship between performance and censorship, from the critical perspective of Cuba? To your mind, how are issues of censorship mediated, tolerated, negotiated, and challenged in Cuban performance practices, and how do such issues shape the way performance has developed and is developing in Cuba?

CF: I would have to recapitulate the entire book in a brief answer here to respond to your question! Many of the performances I talk about in the book were censored. Engaging in political confrontation as an artist is not usually acceptable in Cuba. There are elements of the penal code that refer to anti-socialist behavior, public scandal, and showing contempt for authority that are sometimes applied to artists. I try to explain how and why censorship happens in Cuban art – because artworks can be stopped by different entities for different reasons. A performance in a public venue that has not been authorized could be stopped by police if it is happening on the street, or by gallery or museum staff if it is occurring inside. A performance that is considered an affront to leadership can be stopped on the basis of content by cultural bureaucrats or Communist Party officials. A performance that is considered a threat to national security because of inflammatory content or simply because it promotes a rebellious attitude might be investigated by state security.

It does not make sense to separate how performance has been affected by the authoritarian state in Cuba from how culture and public expression, in general, have been affected. Everyone in Cuba knows there are limits as to what one can do in public. Art is sometimes treated as something of a protected space, where a small elite can say and do what others cannot. But there are limits and also the decision of what is acceptable is not the artist’s to make. That is up to those who act in the interests of the state.

Coco Fusco is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, and the Andrew Banks Endowed Professor of Art at the University of Florida. She is a recipient of a 2014 Cintas Fellowship, a 2013 Guggenheim Fellowship, a 2013 Absolut Art Writing Award, a 2013 Fulbright Fellowship, a 2012 US Artists Fellowship, and a 2003 Herb Alpert Award in the Arts. Fusco’s performances and videos have been presented in the 56th Venice Biennale, two Whitney Biennials (2008 and 1993), BAM’s Next Wave Festival, the Sydney Biennale, The Johannesburg Biennial, The Kwangju Biennale, The Shanghai Biennale, InSite O5, Mercosul, Transmediale, The London International Theatre Festival, VideoBrasil and Performa05. Her works have also been shown at the Tate Liverpool, The Museum of Modern Art, The Walker Art Center and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Barcelona. She is represented by Alexander Gray Associates in New York.

Fusco is the author of English is Broken Here: Notes on Cultural Fusion in the Americas (1995); The Bodies that Were Not Ours and Other Writings (2001), and A Field Guide for Female Interrogators (2008). She is also the editor of Corpus Delecti: Performance Art of the Americas (1999), and Only Skin Deep: Changing Visions of the American Self (2003). Her new book entitled Dangerous Moves: Performance and Politics in Cuba was issued by Tate Publications in London.

This article was first published on www.ibraaz.org. Reposted with permission of the publisher. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Stephanie Bailey.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.