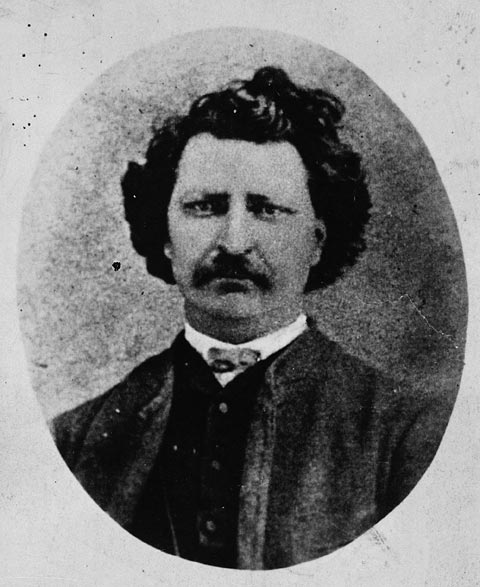

Taking my seat at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts, to watch the 2017 debut of the Canadian Opera Company’s Louis Riel, I snap a photo with my camera. Immediately an usher appears to tell me that I can’t take photos because the set design is copyrighted. I’m surprised by this, as the image used is derived from a public domain photo of Riel, something that many Métis rightfully regard as part of our historical tradition.

Louis D. Riel, photograph taken between 1879 and 1885. Library and Archives Canada

I’m also annoyed that five minutes before this Nisga’a artists—represented by the Git Hayetsk and Kwhlii Gibaygum Dancers—told opera-goers on the theft of one of their songs by the opera’s composer, a lament song from the House of Sgat’iin. After contacting the COC, they had worked to educate the audience and the COC on the composer’s theft of one of their sacred songs using Cree words in place of Nisga’a ones and renamed the Kuyas Aria (read their critique in the opera’s program here).

The irony, of course, was that while the opera appropriated Indigenous songs and stories, my photo for Instagram was somehow violating the intellectual property of one of the many non-Native people who had decided to remix Indigenous culture, history, and imagery for the production. It is as if everything that once belonged to us now belongs to “everyone,” and that in the name of art all is open to appropriation—and eventual ownership—by Canadians.

All of this is a microcosm of the larger issue with this opera: the seeming disregard of cultural ownership and societal integrity of Indigenous peoples. The appropriation of a Métis political epic to tell a story about Canada to Canadians: songs and stories, removed from their original context, tell affirming stories about Canada without regard for Indigenous investments in our own histories.

Louis Riel is a key nation-builder for the Métis people, he is part of an important national tradition that involves resisting the claims of outsiders who would claim our lands and govern us. Riel led two armed movements against Canadian imperialism. The first led to the creation of the new Province of Manitoba in 1870, a development that was intended to facilitate the Métis Nation’s entrance into Confederation, a process undermined by British and Canadian soldiers. In 1885 he led the second agitation, which led to the mobilization of Canada’s army and the invasion of a Métis community at Batoche. Riel was hung for treason by Canadian authorities that same year. He’s a household name in Canada and every Canadian child learns about him in public school, if not earlier.

However, the story of Riel and his “rebellions” have been repeatedly used to reimagine—and ultimately sanitize—the story of Canada’s origins. In fact, the overwhelming majority of writing on Riel is by non-Indigenous authors. Ultimately, the opera as well as countless written works on Riel, (like the Nisga’a lament song), is treated as a story without an owner, available for use by Canadians for their own purposes.

The opera itself is a product of its times, originally written for the Canadian Centennial of 1967, it embodies a radical sixties vision of both Riel and Canada, a time in which Canada’s conservative social values were replaced by more progressive sentiments. Louis Riel is a classic tragedy of a man who struggles with both internal and external demons, and while these are initially under his control, in true operatic style, they inevitably unravel destroying all that he cares about, making him witness to all possible indignities before his ultimate demise.

Photo: Michael Cooper

The story is powerful and as many point out, opera is not where you go for history. But as a work that has been repeatedly mounted at key nation-building moments for Canada, it’s definitely already a politicized work that claims to present us with a nationalist Canadian history. It’s no mistake that it has been performed for Canada’s centennial in 1967, Vancouver’s Olympics in 2010, and now in 2017 to celebrate Canada150.

In the 1960s, the period in which Louis Riel was originally written, the Canadian view of Riel was undergoing a radical change. In English Canada, he transitioned from an insane pariah leading semi-civilized half-breeds in an attempt to break up Canada, becoming instead a relatable cultural hero that stood for all the best progressive values quickly becoming central to Canada’s changing national identity—multiculturalism, bilingualism, an equal place for the West in Confederation.

That Canada executed Riel while expropriating Métis lands was rarely considered in this mythmaking that linked Riel with Canada. It overrode a history of resisting Canadian expansionism in favor of ongoing Indigenous independence, the centerpiece of Riel’s political vision. Therefore, Riel’s reinvention as a Canadian icon does not prioritize political justice for the Métis Nation or other Indigenous peoples, but instead a more palatable story about the development of progressive Canadian values, which were changing dramatically during the 1960s.

Emerging from its sleepy loyalist-inspired Toryism, the 60s ushered in an era of new progressive values for Canada, Riel emerged as the new mythic repository of these new values. He symbolizes this new vision for Canada, one that was “Indigenous” to the country but also have European influences—something reflected in popular conceptions of what it means to be Métis. Riel became symbolic of Canada, or even Canada personified.

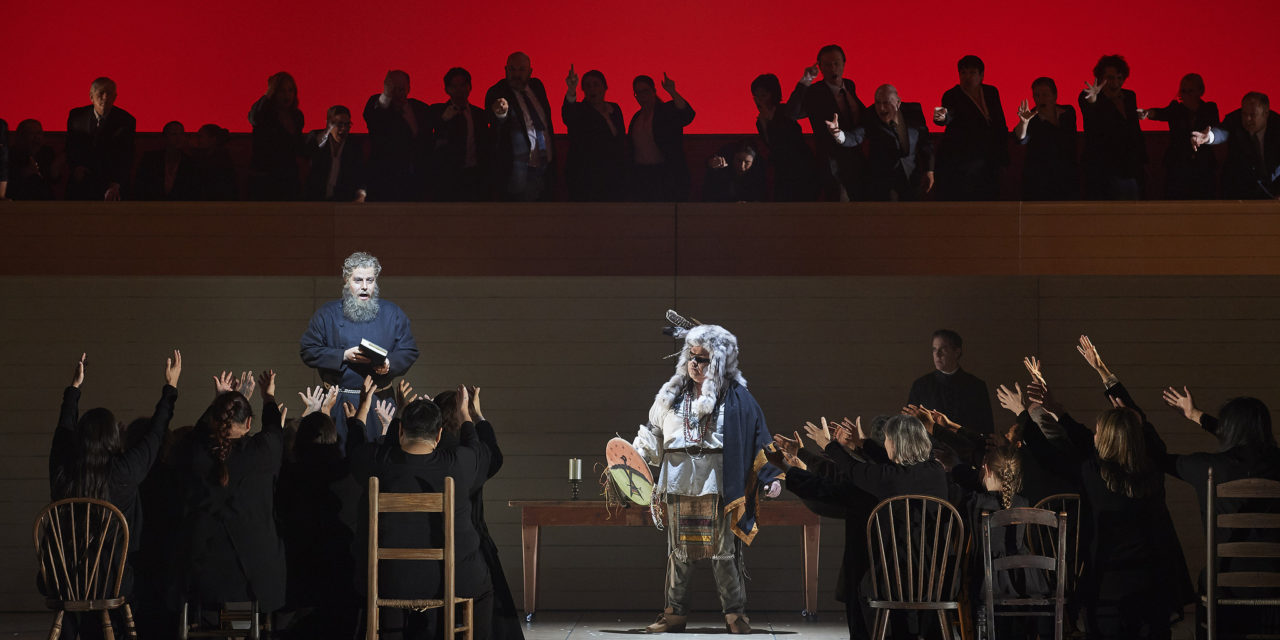

The opera portrays Riel as a tortured soul, identifiable to many Canadians who in the 1960s possessed a value system at odds with the powerful political institutions of their day. Riel is the leader of a cause ahead of its time, wrestling with powerful conservative forces in Eastern Canada, he envisions a new society that will transform the old—that this society would be Métis seems to be lost in much of this mythmaking—but the struggle remains relatable, as the Riel of 2017 battles the scotch-drinking 1% in their board rooms high above the rest of us, just as he battled his political opponents in the 19th century.

These conservative power brokers are represented by a scheming Sir John A. Macdonald, who, wearing a loud, red, Don Cherry-style plaid suit, struts around as an overconfident boorish man, talking over his ally Georges Cartier (in a similarly-styled blue plaid suit), talking down to Donald Smith in an HBC blanket themed suit, and an easily fooled Archbishop Taché. These four men meet repeatedly debating matters of great import, and as the opera unfolds it becomes apparent that they are the real forces of history, not the titular Riel. Riel is left to react to their decisions. His destiny is to lose nobly, but in doing so will sacrifice himself to inspire a better, more cosmopolitan Canada.

The Métis in the opera are comparatively silent. Indeed, outside of the Riel family—Louis, his sister Sarah and mother Julie—few Métis speak. The Métis in the opera are uncharacteristically silent, much different from actual Métis politics. Riel’s lieutenants, Ambroise Lepine and Gabriel Dumont get some dialogue, but it’s mostly incidental. Métis have some stage presence when they occasionally emerge out of the background but are mostly there as props.

The 2017 production attempts to overcome the lack of Indigenous voice, succeeding in increased presence of Indigenous bodies, but ultimately fails to address the foundational issue of Indigenous voicelessness. To ensure some degree Indigenous presence, a “Land Assembly” was added for the 2017 production. Comprised exclusively of Indigenous actors, the Assembly is present in almost every scene to keep silent witness of the unfolding plot.

Their physical presence is moving—indeed powerful—but except for a little narration, the Land Assembly is silent throughout. While the Assembly’s performance is itself powerful and the actors themselves project an immense physical presence on the stage, that Indigenous people are yet again silent in almost all regards while white people trample over top of them, does little to challenge the underlying narrative of this work.

Contrasted to the silent Land Assembly is a loud “Parliamentary Chorus,” a group of Canadians that spends much of the performance seated above the Land Assembly and Métis (but never lording over Macdonald & Co). They have a voice, a very loud one, and at times shout down Métis characters, particularly at Riel’s trial, when he both literally and figuratively is drowned out by a white, suit-wearing chorus. In determining the power to speak and be heard, the opera reproduces an old trope, that Indigenous people are noble, voiceless, romantic, and ultimately doomed to lose.

The way Indigenous silence is portrayed in this work—ironically about Indigenous resistance—only succeeds to projecting a voicelessness backwards in time to re-imagine a weakened Indigenous world in which few spoke up about their oppression. Even with the COC’s attempts to remedy some of the issues with Indigenous voice, the limitations of the original work leave us with silent and stoic Indigenous presence.

Adam Gaudry, Ph.D. is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Native Studies and Department of Political Science at the University of Alberta. His research focuses on Métis politics, history, and identity, and often writes about how these things are portrayed in Canadian arts and culture.

Originally published on adamgaudry.wordpress.com. Republished with kind permission of the author.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Adam Gaudry.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.