What is it about Alexander Calder’s mobiles that make them so ineffably charming? Is it the clever combination of bold, purist abstraction and airy whimsy? Or perhaps the understated genius of incorporating movement into an otherwise by-definition stable form? It may just be the fact that they’re so gosh darn familiar to us by now – who didn’t make a mobile at some point in elementary school?

The Hypermobility exhibit on the top floor of the Whitney, on view until October 23rd, brings many of Calder’s rare pieces together in one place, with the added bonus of the sculptures being “activated” at certain times during the day. Refreshingly, the space is less like a museum and more like a gallery: a single, manageable-sized room with legible labels and not too much explanatory text, everything drenched in sunlight due to the building’s beautiful glass-heavy design – a direct contrast to its former, blocky building on the Upper East Side, now called the Met Breuer. The new design is undeniably fun (at least in the summer), since you can navigate the floors of the building through outside staircases, and it’s likely you’ll encounter more people photographing the view than the art – indeed, the city itself feels like it’s an exhibit from the vantage point of the Whitney.

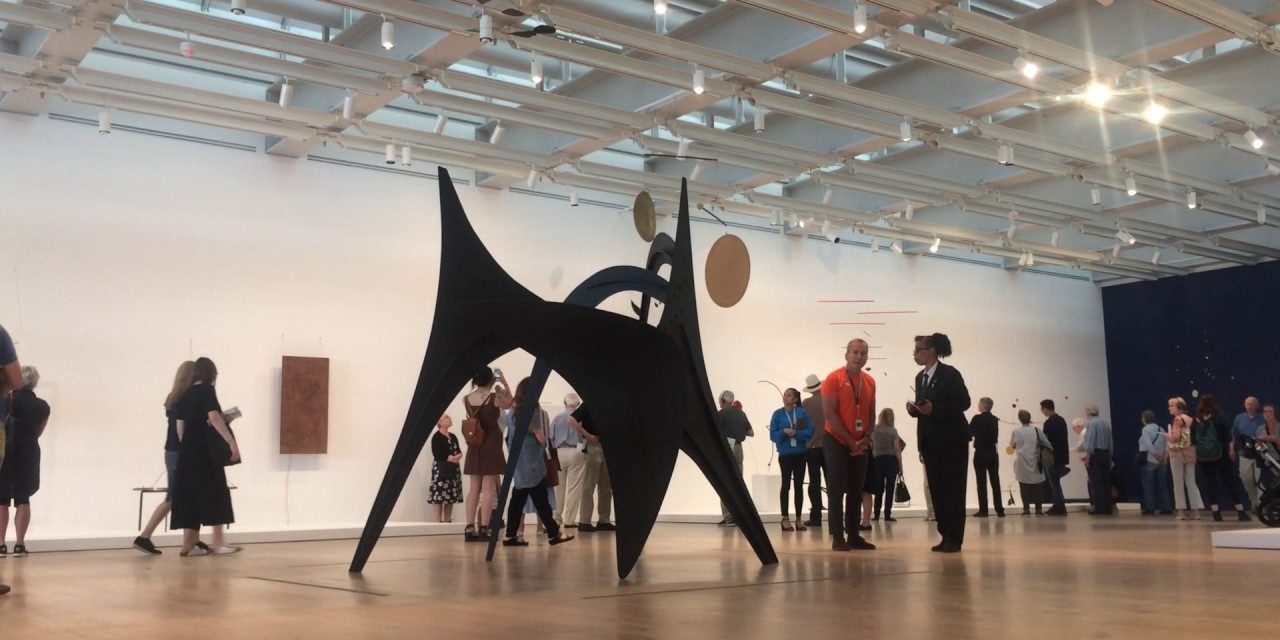

Upon venturing to the top floor, be it by staircase or elevator, the viewer is greeted by the large spider-like sculpture in the center of the room, The Arches, which gives a visual anchor to space, and also links to a similar piece on view on the terrace one floor below. It seems quite Calderian (to coin a phrase) that three of his sculptures hang from the ceiling, their paint-palette shapes gliding in their endless wind chime dance through mid-air – they may be the three strongest pieces of the show, in fact. Certainly, the large gong and mallet that float tantalizingly towards each other, never quite striking strong enough to make a sound, is a visceral study in toying with viewers’ anticipation.

Isn’t that the essence of these works, the tantalizing sense of anticipation? There is unquestionable temptation to reach out and touch the sculptures, or perhaps simply blow on them to get them going. The museum is obviously aware of this since they’ve chosen to incorporate the scheduled “activations.” After a bit of wandering, I returned for the scheduled time; the room was full and teeming with anticipation, even impatience. The docent arrived with a long staff which he used to lightly poke a few choice sculptures – the first poke setting off an almost comical wave of oohs and aahs amongst the crowd – it felt like a messiah was among us, the crowd following him to each sculpture he activated. In a skeptical, secular world, art objects celebrating temptation are our religious icons.

I was disappointed he only set in motion four pieces, and only one of them motorized. I asked a friendly-looking docent about it, and she informed me they only do four random pieces at a time, for preservation’s sake, and then offered me an iPad with videos of the others in motion (these can also be accessed on Whitney’s website). The disappointment I felt was a part of the experience of Calder – since, really, what do we expect them to do? They dangle in a purgatorial space between endless anticipation and disappointment, of satisfaction and dissatisfaction – much like life, really. It’s a testament to Calder’s craft that one cannot help but picture the entire room in motion as an immersive, joyful ballet of bobbing and twirling sculpture – but I suppose for that there’s always the theatre.

Calder: Hypermobility is at the Whitney Museum of American Art, 99 Gansevoort St. in New York City until October 23rd.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by John Tilley.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.