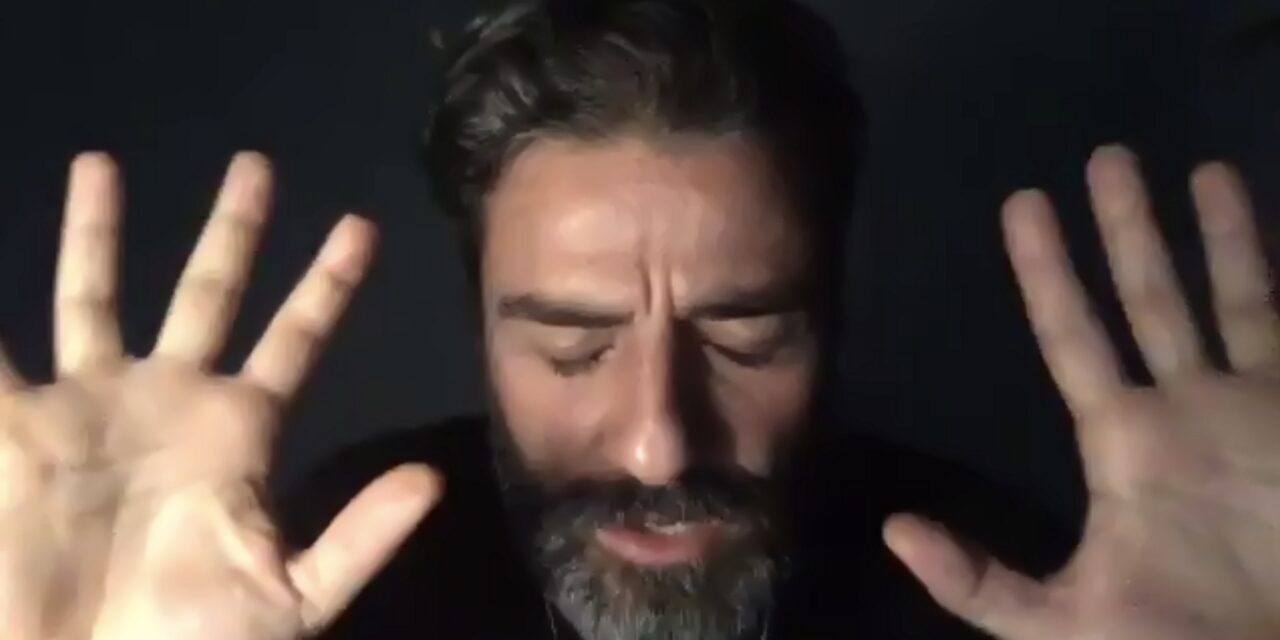

The frame lingered some seconds too long on Frances McDormand, playing Jocasta, just long enough to glimpse her listening mournfully, painfully, to Oscar Isaac, playing Oedipus. On a stage, it would have been the stuff of theater magic, the mark of a sublime actor of McDormand’s caliber fully inhabiting her role. But Zoom is no stage: “We lose the ability to affirm each other,” is how Bryan Doerries, director of Theater of War Productions’ The Oedipus Project, described the tool’s most vexing constraint. For the one-time Zoom event, which began with a live reading of Oedipus Rex, the group made use of a spare visual logic: only one frame visible at a time, hiding the rest of the cast until their turn came to speak. Had it not been for a janky transition from one speaker to the next, that moment might have been lost to the audience entirely.

For a medium like Zoom to mature, it needs to venture into territory theater and television cannot reach. Its interactive potential, for example, has so far been under-explored. Watching along at home, with an Old Fashioned in hand and my family playing board games in the next room, my attention was fickle at best. Distracted, “pants-optional” viewership might be enough for comedy — a notable few have succeeded — but is a hard sell for the full-bodied demands of tragedy. One way to pull it off, it turns out, is to run the show more like a video conference, less like a live stream. The performance was only the first of three distinct acts to the evening, followed by a panel discussion. During the final audience discussion portion, the ‘Raise Hand’ feature of Zoom was enabled, and any viewer, if called on, could be elevated to the same prominence as the actors onscreen. I was drawn to the possibility that I might participate. Video conferencing is nothing if not egalitarian, cramming everyone’s bad haircuts, eccentric lighting, and poor styling choices into the same dreadful grid (the Brady Bunch meme is forever ruined) — as well as utterly novel to both theater and television. Bringing the audience into the frame activates their attention differently, in a way unique to this medium. I put on lipstick, just in case.

What transpired during The Oedipus Project was hardly about reciting an ancient Greek text on Zoom. “Ninety-nine percent of what we do is about curating audiences with skin in the game,” Doerries said: “What tragedy does,” then, “is it returns very predictable results.” For more than a decade, Theater of War Productions has perfected their live events over thousands of performances, enlisting tragedies from the classical canon, its actors pushing into the highest emotional register possible for each role, aiming, as Doerries explained, for impact: “can we hit an audience hard enough to perturb it?” They are known for performing in places where they have an opportunity to rearrange the hierarchies of how culture is received: in homeless shelters, inside jails, before servicemen who have seen war firsthand. By privileging proximity to suffering, they give people who are otherwise unlikely to step into a theater access to their own emotions. “It’s a psychotropic tool,” Doerries said: “Short of giving one thousand Marines MDMA, you’re not going to get them to open up the way we do.” The real performance is the ensuing conversation—and success, as Doerries sees it, is in upending social convention enough so “the lowest ranking person, the person who felt he or she didn’t have a right to be speaking, is the one speaking.” This signature approach adapts remarkably well to the video conference format.

Not a plague play per se, Oedipus Rex nevertheless touches on urgent themes of the moment: pestilence and crisis of leadership. It was a canny choice for framing a conversation around crisis at the pandemic’s epicenter, with New York City leaders invited to comment during the panel discussion part of the event. Covered in protective equipment — “I am an apparition” — Anthony Almojera, an EMS technician, recalled the daily ordeal of entering the homes of those hanging between life and death, each new space a story told in furniture and tchotchkes: “You see a life full,” while at the same moment “you see them as their life is leaving them.” Unscripted, unrehearsed, his words had the moving power of a poet and everyman—as did the ensuing audience discussion. It was unlike any conversation I have ever experienced. The initial ritual of reading through the play, distant in time, place, and cultural context, had given everyone — actors, panelists, audience — a heightened syntax for describing their own, lived experience: “Have a foot in both worlds, that’s what we’re asking the audience to do,” Doerries said. Within the world of the story, Oedipus Rex enacts a public gathering: his crimes of parricide and incest already in the past, Oedipus discovers his guilt in front of a group of onlookers, the chorus of citizens of Thebes, becoming, by their gaze, ashamed. Watching online, that public gaze, so critical to the turn Oedipus must make from guilt to shame, is missing. Alone in our rooms, cocktails in hand, Oedipus remains merely guilty. By a purely mechanical device, Zoom offers a unique opportunity to bring the audience into the frame, so that we see the audience listening. Theater of War Productions’ inspired use of this feature provided access to a new kind of collective gaze, a way of affirming and being affirmed in the moment.

George Steiner declared tragedy dead, arguing in the 1960s that tragedy’s central function, to inspire fear and pity, is only pertinent to a society that believes humankind to be at the mercy of larger forces — those forces invariably being divine. In the modern world, we understand human suffering is man-made, the result of war, systemic inequality, genocide. We no longer fear gods, but each other. Steiner was not wrong to insist that a broader social context is crucial to the mechanics of tragedy — it is just that he died too soon, in February of this year. One month later, the world would come to a standstill because of a novel virus — as poorly understood and indifferent to human suffering as any god, wreaking havoc in our human affairs. There is an argument to be made for tragic forms becoming resonant anew now — via video conference if necessary — if that is the best means at hand for some form of public gathering. The work of teasing out this unlikely medium’s unique poetics is also the work of trying to make sense of our new collective suffering.

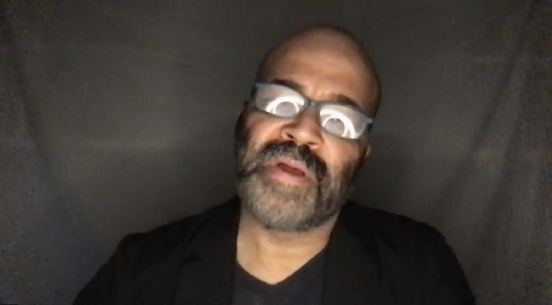

Image courtesy of Theater of War Productions.

The Oedipus Project by Theater Of War Productions. Premiered May 7, 2020, on Zoom. Cast: Frances McDormand, Oscar Isaac, Jeffrey Wright, John Turturro, Frankie Faison, David Strathairn, Marjolaine Goldsmith, Glenn Davis, and Public Advocate Jumaane Williams. Panelists: Jo-Ann Yoo, Paulette Soltani, Dr. Rob Gore, Anthony Almojera. Directed and facilitated by Bryan Doerries.

Kat Mustatea is a playwright and technologist. Her TED talk, about algorithms and puppets, is available here.

This article was originally published on EdgeCut, and has been re-posted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kat Mustatea.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.