Anna Karenina at the Moscow Operetta Theatre is an original musical adaptation of Leo Tolstoy’s iconic novel, brought to the stage by producers Vladimir Tartakovsky and Alexei Bolonin with a libretto by acclaimed Russian poet and playwright Yuliy Kim. The production is bold–but misses the mark.

Most importantly for foreign Tolstoy’s international aficionados, Russian language skills are not a prerequisite for enjoying the show. Although performed in Russian, English language programmes with synopses of each scene are sold, ensuring that international audience members are not left scratching their heads. The ensemble scenes, particularly the Skating Rink in Act I, are visual feasts conjured by trained figure skaters and ballet dancers. Choreographer Irina Korneeva innovatively blends classical and modern styles, giving the show a distinctive and memorable aesthetic, while costume designer Vyacheslav Okunev provides the glittering sartorial sumptuousness that we expect of Imperial Russia.

Anna Karenina Musical at Moscow Operetta Theatre. Photo from the original article.

Tolstoy’s novel is almost 1,000 pages long so it is only natural that it had to undergo substantial trimming in order to fit a two-hour musical format. As expected, much of the author’s philosophical musings are omitted. Levin pondering the injustices of serfdom, and his ambivalent attitude towards his ailing brother’s mistress, is nowhere in sight. On the whole, these cuts are understandable and adequately simplify Tolstoy’s sprawling narrative for the stage. However, there are times when one is left wishing that some of the original complexity remained. The novel’s famous opening scene in which Dolly discovers that her husband, Anna’s brother Stiva, has been unfaithful is omitted entirely. The poignant contrast between Stiva’s socially accepted infidelity and Anna’s disgrace is, thus, lost.

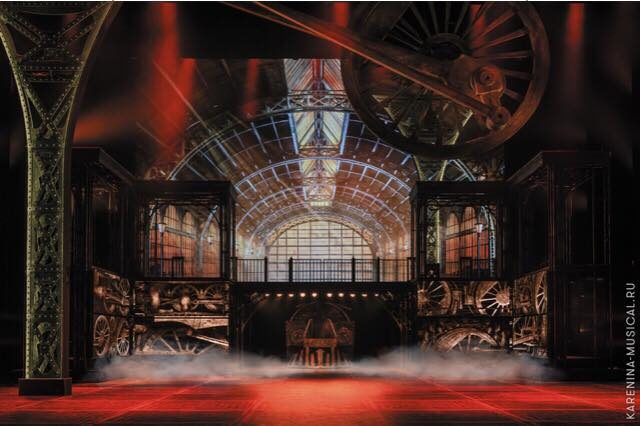

Anna Karenina’s creators have imported a format familiar to Anglo-Saxon audiences in which the protagonist is shadowed by a “Narrator” figure who seemingly controls the action while offering scathing or ominous commentary upon it. The form was popularised by Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar (1970) and Evita (1978) in which Judas and Che take on this role. In Tartakovsky and Bolonin’s production, it is the Station Master. Anna Karenina’s creators may have borrowed a character type, but they do so with skill. The invented Station Master figure lends a thrilling and sinister edge to what could have been a rather banal and romantic adaptation, staying true to the tragic omens that Tolstoy scatters throughout the novel.

Anna Karenina Musical at Moscow Operetta Theatre. Photo from the original article.

Say “Musical Theatre,” and one is likely to think of New York or London–not Moscow. That the art form does not have deep roots in Russia is clearly evident in Anna Karenina. Broadway and West End Musicals are multimillion-dollar industries with seamless productions and spectacular sets. The set of Anna Karenina is dominated by four mobile podiums and a large backdrop onto which interiors and landscapes are projected. The podiums worked well given the relatively small stage, but the projections were poorly designed, lacking intricacy or naturalism.

The hallmark of a good Musical is whether the audience leaves humming the songs. Think Memory from Lloyd Webber’s Cats or You Will Never Walk Alone from Rodger and Hammerstein’s Carousel. Sadly, Anna Karenina’s composer Roman Ignatyev does not offer any such gems. There are glimmers of potential in the Station Master’s pulsating, minor-key, theme which opens and closes the show. Most of the music, however, lacks originality. Save for the operatic-style aria in Act II, all of the songs are reminiscent of 1980s pop ballads. Kitty’s mournful number after she is rejected by Vronsky–the main lyric of which is Home–is the worst offender. The actors–all highly trained and experienced–deliver them with gusto and strong vocals, but their skill is not enough to cover the absence of musical innovation.

Anna Karenina has become the first Russian musical to be produced under a license abroad and has won the accolade of “Most Popular Show of 2018” from Ticketland.ru. It is clearly not without potential and marks another daring step towards the creation of a native Russian Musical Theatre Scene. Will Moscow ever have its own Great White Way? Although flawed, the glimmer of potential in Anna Karenina suggests it might.

This article was originally published on Russian Art and Culture on December 9, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emily Couch.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.