Emiliia Dementsova reports from Moscow with a review of Konstantin Bogomolov’s The Magic Mountain at the Stanislavsky Electrotheatre.

The Magic Mountain, if it is indeed a theatre show, as is implied by its port of registration (the playhouse, that is), into which the entrance ticket, the playbill, the posters, and the media reviews do their best to persuade us, then it is a theatre show that is desperately struggling against all these attributes. It is an act of presence: effected by the author, the director, the audience, and the actors (or, since it is all about the mountains, the route guides) to help us about the text… It cannot but bring to mind Marina Abramović’s The Artist Is Present, and not only because the director made use of his own writings to stage this show, nor because the performance as an art form runs strong in this production, but also because the “audience response” hasn’t changed all that much since her time…

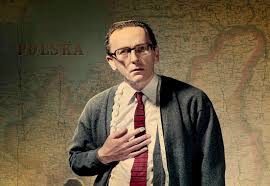

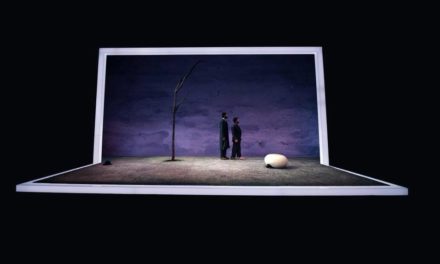

The triangle being the best balanced of all geometrical figures, the structure of the show features three dominants: Konstantin Bogomolov, Elena Morozova, and the space created by Larisa Lomakina. The space is truncated, bracketed by two black planks on the sides, by the blinders. On entering the house the members of the audience spot in the aperture the director, who is sitting in a corner. The space in which he is placed is a sort of limbo, or a charnel-house, built of squares as if touched with rust. The transformations that the scene of action is to undergo as the show unfolds are to take place in the minds of the audience. At times the walls will seem to be showing postmortem lividity, or suddenly, outlines of paintings long destroyed by rot, devastated by time will show through.

The Magic Mountain at the Stanislavsky Electrotheatre, directed by Konstantin Bogomolov, photo by Olimpia Orlova

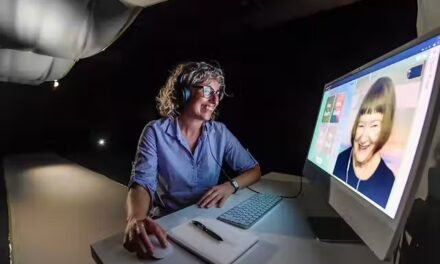

Full view is an impossibility—from the first row, or from the last, or from the sides, or from the seats in the middle. One would think that the screen placed to the left of the stage might help one see that which is blocked from view; but no, the view it offers is also limited by the same black planks. The camera is covering the show not from the inside of its space, but from the outside, from a point that is much like the audience’s point of view, thus importing the minimum of information. Later the camera will start roving slowly over the walls, at times capturing close-ups of the actors’ faces. But the faces turn out blurred. The simultaneous screening fails to allow the living to gaze on the dying.

The members of the audience hardly have time to take their seats, when they are exposed to the sound of coughing—this becomes the continuous aural symbol of the show. Normally it is the prerogative of the audience to cough occasionally during a show. But the circumstances of The Magic Mountain appropriate this right. The dots of this elliptical coughing punctuate the whole of the show—coming as muffled, agonizing, feverish, sobbing, stifling, pressing life out of the body, painfully strained or soundless. From sympathy to irritation: the coughing gnaws away not at the actress alone, but at the audience too, who switch to interpreting this sound effect as a nuisance. The audience starts to echo the on-stage goings-on in a “coughing match” of sorts, attempting to parody the scenic effect. The match is accompanied by tittering, giggles, and whispers. There is also the automatic imitation reflex to consider: when everybody around is coughing, even those who have no intention of interfering with the sound arrangements of the show feel an itch to clear their throats.

The noncompliance of objectives brings about the audience’s frustration: the audience proposes, but the director disposes. Incomprehension, exposure to the unaccustomed breed’s aggression. The darkness enveloping the audience, the dissolution of individuals into the crowd, the fact that conventionally members of the audience are anonymous to the actors on stage, the feeling of belonging to the majority, act as a trigger for some members of the audience, making them bolder, bumptious, behaving in ways they wouldn’t dream of behaving in broad daylight. Normally people admire an actor if he “knows how to sustain a pause,” but they find no excuses for a show that keeps up wordlessly, in silence. Especially since some habitually evaluate a show by the number of plot developments per unit of time, and they expect thrilling turns, action, as something due, something that the price they have paid for the ticket ought to be automatically converted into. Some members of the audience seem to find it hard to bear the privacy of just sitting in the darkness and silence of the playhouse, with nothing to drown your own thoughts, contesting to catch your eye.

The text of the novel is never rendered literally, yet the show is not meant to be a deceitful trick played on the audience; it is indeed a show based on Mann’s novel. Bogomolov has reflected The Magic Mountain in the mirror of the stage by means of other texts, as well as sounds, music, visual imagery, the geometry of space. Bogomolov offers the audience the very essence of the novel, with its “water” constituent evaporated, as well as everything else that connected it to a specific time, place, actions, and characters. Bogomolov does not alter the text, nor does he betray it or fail to stay faithful to it. It sounds paradoxical, yet a show that contains no pieces of the author’s text whatsoever may become the truest representation of it on stage. Here we have a novel—that never suffered castration, that avoided the procrustean bed of adaptation for the stage, as well as translation (necessarily damaging) from the tongue of belles lettres to that of the audience—presented as a phenomenal experience, with the audience being immersed in it literally. Some see it as a provocative gesture, others as an “interpretation driven to its utmost boundaries.” Even reading the text of the novel aloud would have been less true, since it would come contaminated with alien intonations, failing to render the principle by which the text is structured, the pauses, the rhythm…

The Magic Mountain at the Stanislavsky Electrotheatre, directed by Konstantin Bogomolov, photo by Olimpia Orlova

This is a show that “by death has trampled death.” The point is not that conversations about death without grievous reverence and with joking at its expense help overcome our fear of it. Neither the director’s theory of canceling death, which has worked in practice once again nor, consequently, the category of development in art, are the point. The beginning, the middle, and the finale of such a show ought to be of equal value, of equal interest, despite the traditional forms that normally rely on a striking opening and finale, divided by a range of middling scenes. This show about death—that is, about the inevitable tragic finale—doesn’t break the routine. Except that it rejects the very category of the finale. Here they just walk on death. Only in art is this sort of soaring between the beginning and the ending possible. The show lacks both the former and the latter, both death and the mirror image precursor of it, birth. The life of a show is short as it is (an evening-long), but it may take in the whole of eternity.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Emiliia Dementsova.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.