The Tailor Of Inverness, a Dogstar production which premiered at Chats Palace in Hackney last week, tells the story of Mateusz Zajac, a Polish tailor from the former Eastern Polish region of Galicia. First performed at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2008, the play’s told by Zajac’s son Matthew, the writer and the actor, who follows his father’s journey across Europe, from Poland, through Ukraine, Russia, Uzbekistan, Iraq, Syria, Italy and Germany to Inverness, Scotland, where he settles. Those familiar with the history of Europe in the early twentieth century will know it as a story of horror and tears just in itself. But this is more: around this central narrative, the writer Zajac invites us to share a very private story with him.

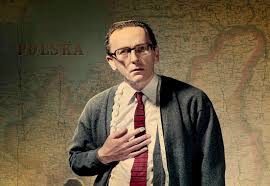

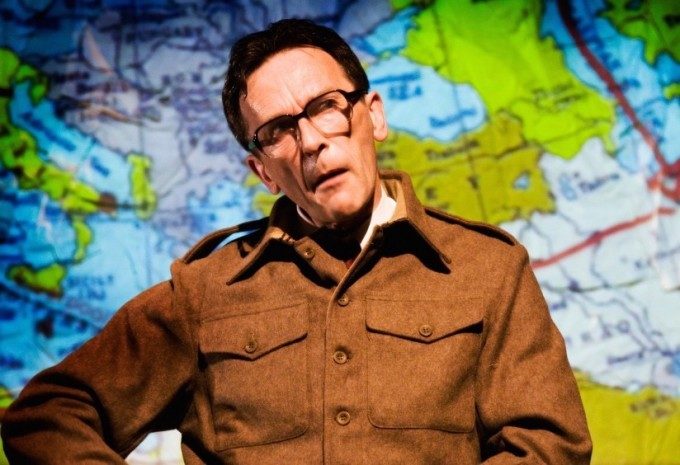

You realize very early on this isn’t just a historical account of his father’s journey. The tailor lifts a coat off the rack onstage and tells the audience “This is for my son.” Well, the play is for young Matthew too, and for his father Mateusz, and for their family, and we’re privileged to be a part of it. It’s a story about real people, an intimate look into the real Zajac family. We learn about his father’s character, the jokes he used to make, and about his past: never easy, and at times horrifying. Meanwhile, the writer tells us something of himself, of his relationship with his father and family as he takes us on his journey of discovery. There’s something deeply affecting in seeing a son play the part of his dead father, then playing himself and Mateusz in a dialogue with each other. You can’t help feeling the emotion that must have gone into writing this play while wondering if the actor is feeling it as strongly as his character appears to.

Zajac plays his father in an amusing, even masterful hybrid Polish-Scottish accent that has to be heard to be believed. Sometimes Mateusz has conversations with his son Matthew, and the dialogue, done by one man who flips between his own Scottish and his father’s blended accent, is a marvel. Nor does the play lack humor: the earnest tailor is a cheeky and loveable fellow, and like all Poles, a real ladies’ man. With each woman he describes, he bounds across the stage and adorns a mannequin with a pink scarf, flicking it playfully this way and that.

Zajac shows us clips from the camera footage he took when he went to former Galicia, then Poland, now Western Ukraine, for the very first time to discover where his father was from. We actually see the wind which Zajac saw for the first time through his camera, the wind which blew the corn in the fields of former Galicia. We meet the old women in headscarves who remember old Zajac, who recognize his son Matthew because he “looks just like his grandfather”. This is momentous for Zajac, and as an audience, we can’t quite believe he’s letting us share it with him. Then Zajac gives us an uncomfortable revelation: something he himself never knew about his family. Now everyone knows and everyone shares in Matthew’s shock.

The play is worth seeing, if only for Zajac’s performance. Apart from a very amiable violinist who plays Polish folk songs in one corner of the stage, Zajac is the entire play. How someone can experience so much pain, joy, sadness, and anger in the space of an hour and a half are beyond comprehension, but he does it, and he gets you to feel it too. His energy and scarily expressive face are exhausting to watch, but this is not a play you’d come to for relaxation. The narrative moves quickly, and Zajac leaps backward and forwards in time, through subjects, people, countries, accents, and languages. The absolute focus is key if you want to keep up.

What’s most striking about the play is its originality: whether or not you know the history behind it, The Tailor Of Inverness is surprising all the way through. It’s not light viewing, but the tailor is cheerful and kind in spite of the trials he has had to contend with – which is in itself a lesson for us all

This article originally appeared in Central and Eastern European London Review on March 28th, 2016 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Olenka Hamilton.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.