Whatever preconceptions you have about documentary theatre, set them aside when you step inside Teatr.doc in Moscow. Periodically subject to police raids, bomb threats, evictions, and visits by counterterrorism officers, this tiny independent theatre lives life on the edge. Just a matter of days ago, for example, the theatre was stormed by a group of a dozen Russian nationalists, who disrupted a performance of a play about gay life in Russia, and started a brawl that ended in the arrest of a spectator on charges of hooliganism. This follows other occasions in recent years when plays have been interrupted by Russian Orthodox extremists, accompanied by state TV camera crews. As dangerous or brave as it may seem to outsiders, Teatr.doc has been making hard-hitting documentary plays about the many problems that define life in contemporary Russia for nearly two decades. It has for years now been effectively the only truly independent theatre in the Russian capital, preferring to live a threadbare, unstable existence on the margins of cultural life rather than take money from the state and thereby compromise its artistic freedom.

This policy has not come without its own problems, however. The theatre has come under increasing pressure over the past decade, being forced to move premises three times in the past five years alone, having spent the previous twelve years before that in the same place — to those in the know, the legendary basement on Trekhprudnyi Lane, where it was founded in 2002 by Mikhail Ugarov and Elena Gremina, among others.

Ugarov and Gremina were the driving force behind the theatre for sixteen years before they both tragically and suddenly passed away in spring 2018. Their battles with the authorities have become the stuff of local theatre legend, and it was feared that the theatre would disappear with them as their opponents in local government saw a golden opportunity to be rid of this old thorn in their side once and for all. Fortunately, that didn’t happen, as theatre-makers of the new generation that Gremina and Ugarov had been nurturing under the roof of Teatr.doc were forced to come of age and take the reins of the theatre in its moment of existential crisis. One of those who stepped up to the task and now plays a leading role in the work of the theatre in the post–Gremina and Ugarov era is the young Chechen-Siberian director Zarema Zaudinova.

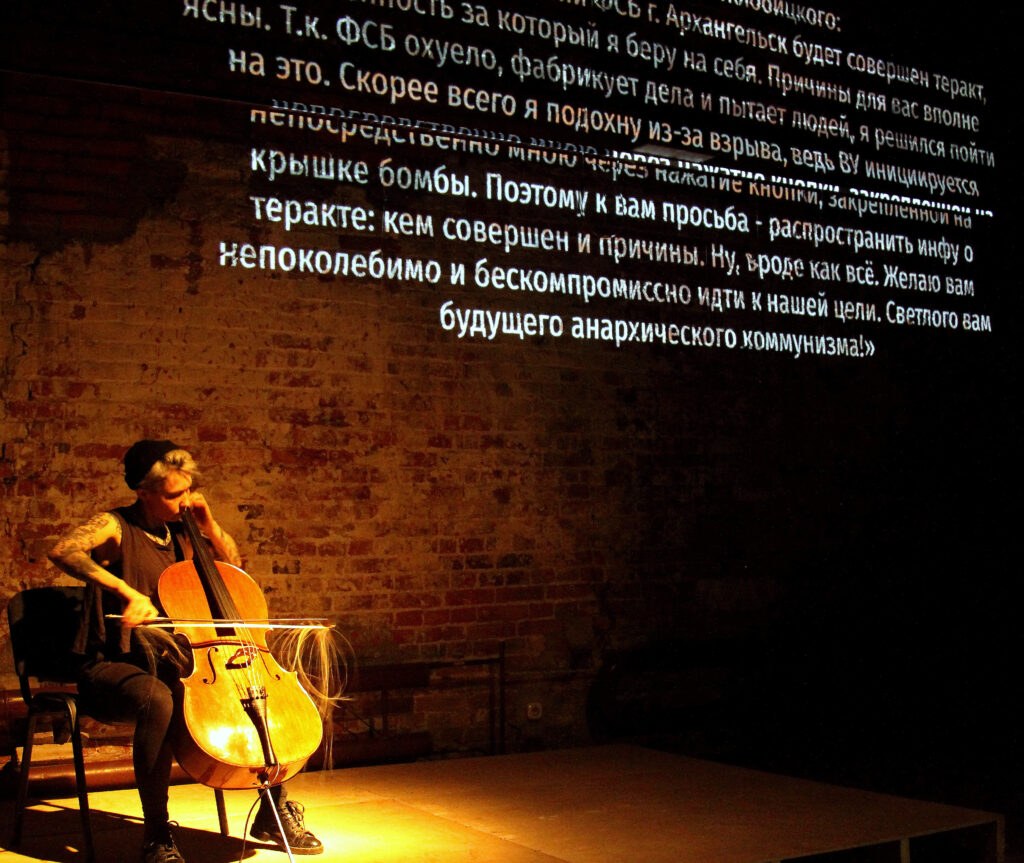

At 29 years old, Zaudinova has been involved in one capacity or another with many of Teatr.doc’s best documentary plays over the past few years, taking on increasingly more responsibility in a relatively short space of time. Her first full production after the unexpected loss of her teachers and mentors Gremina and Ugarov has been a hit in Europe, although it has only been performed a handful of times in its native country. Uncompromisingly named Torture (Pytki), it deals with the scandal and systematic cover-up of the brutal torturing of suspects held in police custody during a 2018 trial in Penza, a city some 600 kilometers to the east of Moscow. The ten victims in the case were repeatedly tortured with electric current (among other methods) into giving false confessions of conspiracy to commit terrorism, and these confessions were then used to sentence them in court to between 10 and 20 years imprisonment. Torture, which premiered at the Sakharov Center in Moscow on December 2018, has since been on a European tour, taking in Berlin, Prague, and Tel Aviv, as well as offering a stand-out performance at the Royal Court in London.

As with many Teatr.doc productions over the past decade, the play has not been without its share of difficulties. The first time it was due to be performed, at a festival in St Petersburg in May 2018, the venue received a call from the FSB (the modern-day KGB) and was told that if the event were allowed to go ahead, the venue would be shut down. On that occasion, the organizers were able to find a new venue at short notice, and the event went ahead anyway. Nonetheless, the message was clear: state-funded platforms are not permitted to stage such work. The organizers thought that performing abroad would lead to fewer problems. However, two days before the play was due to be performed in London, they found out that two of their performers had been denied UK visas. This was on account of the fact that they had criminal records for involvement in anti-government protests in 2012. After the script was hastily rearranged on the flight over to London, an altered version of the play was performed to a full house at the Royal Court in March, to great acclaim from those who were there to witness it. People were reported nearly fainting, and there were gasps, sighs, and stunned silence in turn, as the relentless power of the play bludgeoned the unsuspecting London audience into a state of shock. For the Russian performers, it was just another day in the office — as they explained, this is the everyday reality of Russia at the present time. Most regrettably, not a single review appeared of this show in any British newspaper or on any major media platform. Reporting was limited to word of mouth and social media. Why it did not receive any press is unclear, but for the Teatr.doc crew, for whom media blackouts and blanket silence at home are the normal state of affairs, it was nothing out of the usual.

When I arranged to meet Zaudinova in Moscow to chat about her work, we ended up conducting the interview on a park bench, to be able to speak with maximal freedom. In one of the early versions of Torture, there is a verbatim scene in which Zaudinova discusses the figures in the Penza case with two human rights activists. During the course of the conversation, they casually observe the revolving carousel of agents from various state security services swarm around them, so it is not without grounds that we go for a stroll to find somewhere suitable to talk. At one point she becomes suspicious and breaks off the conversation to point out to me what these agents look like, as a man in shiny, black, pointed-toe shoes, with a large, black leather shoulder bag talks aggressively into a mobile phone. Not that any of this bothers Zaudinova, however. When I ask her why she made this play, she answers in a typically direct fashion, “to not lose our fucking minds.” She explains the feeling of necessity to at least do something about the situation that she and others see in front of them, however dire things get or however great the personal and professional risk. She elaborates:

In March [2018] there were due to be, and there were, presidential elections. And Putin was everywhere. Like you walk out of your house, and there’s Putin. Where I was living at the time, I would come out of the subway and there was always an advert for pizza there. I raise my head, and suddenly there’s Putin! Putin was absolutely everywhere. Putin as a diagnosis – everywhere. It was like, “Make your choice.” It wasn’t only Putin; the Russian tricolor was everywhere too, and “Make your choice.” One day we were sitting there like, “Fuck, we are voting for torture.” By and large, the elections were just a vote for torture. So in response we thought up the slogan, “No elections, torture instead.”

That seems like a fairly apt summary of Zaudinova’s project, which is in part to raise awareness of the issues, not just to shock audiences who come to see the performance. Teatr.doc often holds open-floor discussions with the audience after the show, and these discussions can sometimes go on for longer than the performance itself. One reason for this practice seems to be that in the absence of mainstream reporting on these stories, people generally lack an outlet through which to make themselves heard and to try to make sense of these fragmented leaks of information. On the issue of censorship in Russia, which has over the course of Putin’s two decades in power become increasingly tough, Zaudinova says:

The worst is self-censorship when you do something and have to ask yourself, “Will they arrest me for this or not? What will happen? Maybe it’s best to just stay silent.” Basically, when you ask yourself the question, “Well maybe it’s better to stay silent,” that means that you have to speak about that thing. Art doesn’t exist on safe ground. This isn’t about politics, this is about that liminal state, transgression, however you want to name it. As soon as you start to live on safe ground, for yourself, for yourself as a citizen of a country, for yourself as a person, for yourself as a friend, you cease to exist as an artist.

In making plays about themes that routinely land people in prison on short and long sentences, Zaudinova is one of the few contemporary artists who can genuinely claim to practice what she preaches.

Zaudinova’s fearlessness in the face of an increasingly violent authoritarian state makes those close to her worried for her safety. On this subject, she turns the question on its head and puns, “I’ve got nothing to lose except my own freedom.” It’s a “damned if you do, damned if you don’t” situation when it comes to radical documentary making in contemporary Russia. For Zaudinova, the only way to hold on to her freedom is to make the theatre that she feels needs to be made and seen, regardless of the consequences for her personally. In her view, the issue is about the function of an artist: “When artists complain about it [self-censorship], it’s so lame. Come on, guys, what are you actually for if not to overcome barriers and break them down?” The director explained to me in an anecdote what she perceives as the root of the problem in Russian culture today. She was standing outside of a Moscow airport with a German theatre director who commented on how many signs there were around the city forbidding things: “I came to the conclusion that in Russia, the Bible starts with the line, ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was Forbid.’ With music.”

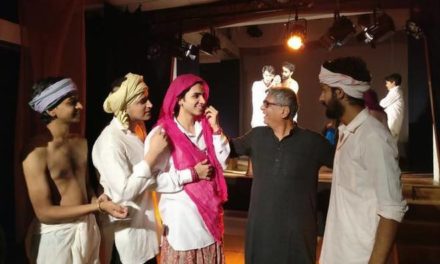

Zarema Zaudinova’s Torture at Moscow’s Teatr.doc. Photo by Vasiliy Petrov.

This kind of irreverence is for Zaudinova a necessity of the new circumstances in the post–Ugarov and Gremina era. Some people charge her with being too radical, but, she retorts:

In this repulsive new time we’re living in, you say that two times two is four and it’s considered outspoken. You say very simple things, and it’s considered a great achievement. You’re like, “Torture is torture,” and the response is, “Bloody hell, that’s real heroism.” Are you insane? Ugarov used to say that all we are doing is asserting the norm. We are just talking about normality here. Only in Russia does a person who speaks about norms become automatically a revolutionary. You’re like, “Torturing is not permissible.” Fuuuuck, she’s so radical! Are you serious? They’re the ones who are radical, not me.

Zaudinova makes it very clear that she has no time for “art for art’s sake” or empty aesthetics. That’s not to say though that her work is purely political. There is a strong philosophical current underlying her artistic practice. For her, theatre is “a method, an instrument with which to get through to Being, because you don’t know how to live. It’s a never-ending process because as soon as you know how to live, you are finished.” Her view of theatre, then, would seem to be a practical approach to ontological investigation. She sees her practice of documentary theatre as a manifestation of this endeavor: “What interests me in documentary theatre, but equally in literature or anywhere else, are the points where consciousness caves in on itself. … When the spectator is sitting and thinking, ‘What the fuck?’” This is the reaction that Zaudinova hopes to get out of her audience in every work she makes.

As for why she turns to the documentary theatre over other forms for the achievement of her artistic aims, she sums up,

I like documentary most of all because firstly you can’t fuck with it, and secondly because reality is much more interesting than any fantasy, absolutely any. That is, the reality in Russia at least. You can’t make this shit up. You can’t think up that the FSB would come out after torturing a guy in custody with electric current and publicly claim that the burn marks on his body were just bed bug bites. What the fuck?! Whose brain could come up with that idea? Only in Russia. It’s probably a professional deformation when you are captivated by fucked-up stuff. That’s why documents interest me. When you’re in the metro, going up the escalator at rush hour, and there’s a vast number of people coming down past you — you’re going up, they’re coming down — and each person has a huge life. And in actual fact, each life is the most interesting play or film, because they are living through and experiencing unbelievable things. You know, when you just switch on your inner dramatist, the world becomes incredible.

***

Torture is playing for free at Teatr.doc in Moscow on September 21. For more information, visit the theatre website (in Russian): www.teatrdoc.ru

For more information about the Penza Case, see article: https://meduza.io/en/feature/2018/06/20/i-caved-almost-immediately

A dedicated website with the most up-to-date information and where direct donations can be made to help the victims of the Penza Case in their ongoing trial can be found at: https://rupression.com/en/

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alex Trustrum Thomas.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.