Beliefs of racial purity and superiority were at the heart of the conflict that brought about the Second World War. It was at this time that Paul Robeson, Uta Hagen and her husband José Ferrer toured the American North with a production of Othello directed by Margaret Webster. This very tour inspired Nicholas Wright’s 8 Hotels, brought to the stage of Chichester’s Minerva Theatre by Richard Eyre.

It’s an uneasy feeling to watch a play fuelled by racial politics in a space populated almost exclusively with white audiences, at a time when a nation’s fate is being driven by prejudice towards migration. Wright’s narrative doesn’t offer much comfort in this respect, recounting Robeson’s ordeals in airports and hotels as a black-skinned traveler. Then there’s the characters’ anxiety over public reactions to his onstage romance with a white female. How the times have changed we’d like to think, yet this window into the past lets in air that somehow has a familiar waft.

But life in the 1940s, as Wright would see it, mirrors art – and the dalliances between actors closely resemble those of their Shakespearean counterparts. Uta (Emma Paetz) is a mismatched Desdemona, her marriage with José’s (Ben Cura) Iago crumbling while her affair with Paul (Tory Kittles) becomes increasingly apparent, also to Peggy (Pandora Colin), who stands outside this love triangle. Still, there are other women in the lives of men too, bringing about melodramatic spectacles of jealousy and betrayal. In this, the play may be read as a comment on the sexual politics of the period. As if the characters’ sexualities were screaming for the sixties to come early. How the times have changed, we’d like to think, yet the steady resurgence of far-right movements reveals longings for these times to return.

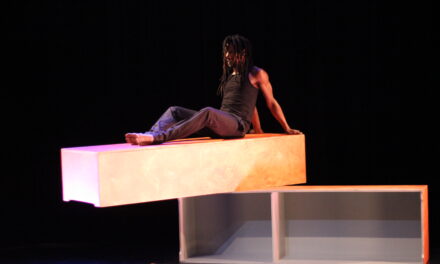

Rob Howell’s set draws on aesthetics of American budget hotels, allowing for smooth transitions between locations with simple changes of bed linens. Minerva’s thrust stage gives an all the more intimate, voyeuristic feel to the experience of spectatorship, particularly so when Kittles stands nude and later struggles to conceal his manhood in boxers that prove too short. The fourth wall stands firm when disgruntled punters start to leave their seats, though Eyre’s direction makes light of its presence, having actors open hotel windows by approaching the proscenium arch and miming the gesture to a pre-recorded sound of sliding frames.

Kittles’ Paul Robeson is a perfect mask of pride and dignity, which suppresses his emotionality for fear of being perceived as a savage. Ben Cura’s José steers clear of one-dimensional villainy, playing his environment strategically like a game of chess. Emma Paetz as Uta remains strong-willed in her battle for feminine domestic freedoms, rhyming with Paul’s plight in political activism. Amongst them all Pandora Colin’s ample portrayal of her character doesn’t give much space to explore the passingly mentioned strife of a female theatre-maker, serving more as a binding agent for the stories of others.

Each of the eight hotel scenes is accompanied by a monologue that explains the action and the nature of the characters’ relationships, which are themselves revealed through nuanced dialogue; I can’t help but feel that I would have managed fine had I been trusted to draw my conclusions. Under Eyre’s careful direction, each beat speaks volumes, and the widely commented scene of a chess match between Robeson and Ferrer is a masterstroke in building tension between clashing egos. Still, Wright admits to taking liberties with the real-life story of this affair, and these seem particularly palpable in the scene where Paul stifles Uta; the narrative allows the relationship to continue, yet a later encounter shows Uta to be terrified of her now former lover. In this the direction seems equally unintuitive, having the actress sitting on the bed next to her oppressor, signaling their past affinity, then jumping to bolt the door the moment he leaves.

It’s difficult not to draw parallels between Paul Robeson and Ira Aldridge. It’s through the efforts of these American actors in challenging casting conventions of their times that white actors in “blackface” are nowadays unacceptable. And their stints in playing Othello were both at the center of plays produced in Britain in the passing decade.

Robeson, in a way, was more “fortunate” than Aldridge; the former was granted the opportunity to play the Moor to Broadway audiences and to subsequently tour the part across the States. The latter, a century earlier, was forced to leave the U.S. to do so, and after having also been rejected by Covent Garden patrons, he toured Europe to considerably greater acclaim. Reportedly London audiences rejected his portrayal of the Moor, perceiving it as an act of revealing his primal, violent nature.

Aldridge died touring. He was buried in Łódź, Poland – where I was born. I remained virtually ignorant of his story until my university years, but it wasn’t until Lolita Chakrabarti’s Red Velvet that I realized its significance. I was then making a living from waiting tables at the Royal Shakespeare Company’s theatre restaurant and came down to London for a matinee performance on November 7, 2012. Kilburn’s Tricycle auditorium was filled with a diverse audience and the minutes before the performance were marked with sounds of rustling newspapers, their headlines announcing Barack Obama’s triumphant re-election. Adrian Lester’s towering portrayal of Aldridge resonated with the political climate of the day. Fast forward seven years and those feelings of hope and progress are replaced with deep mistrust.

It’s in grasping the destructive nature of fear that this production succeeds. Paul Robeson is portrayed as a poor actor, yet his impeccable manners and crisp appearance show him as acting ostensibly sophisticated and civilized. He is ceaselessly performing a persona that counters the very prejudices that sent his predecessor across borders. This deliberateness is poignantly marked in scenes where Uta attempts to coach her partner to tap into his anger to elevate his stagecraft, or when José realizes that Paul sets off to see Uta by leaving their shared hotel room without putting on a tie. This endeavor leaves Robeson scarred. When poised with a dilemma on whether to sacrifice appearances to save a man’s life, he is incapable of making the hard choice. The actor and activist carries on crestfallen, feeling unable to live up to his ideals. The point is, he carries on.

I wouldn’t be opposed to seeing 8 Hotels carry on beyond its brief run in Chichester. With productions such as National Theatre’s Small Island, the body of work created at the Young Vic under Kwame Kwei-Armah, or Sydney Theatre Company’s Secret River, it forms a mighty chorus that can help reshape audiences. Which, in turn, can help reshape something more.

8 Hotels

Written by Nicholas Wright

Directed by Richard Eyre

With Tory Kittles (Paul Robeson), Emma Paetz (Uta Hagen), Ben Cura (José Ferrer) and Pandora Colin (Margaret Webster)

Stage design by Rob Howell

Lighting Design by Peter Mumford

Sound Designed by John Leonard

Video Designed by Andrzej Goulding

Minerva Theatre, Chichester, 1 – 24 August 2019

Seen on August 14, 2019

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Konrad Zielinski.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.