In 1919, following the devastation of the First World War, a movement arose to aid in the rehabilitation of society through design, architecture and general aesthetic practices. The guiding principle was to remove the distinction between fine arts and crafts, thereby infusing everyday life with good taste and beauty. It was called Bauhaus, and the world never looked the same again.

Well, Germany wasn’t the only place where these ideas took hold. At a titillating event this week in Midtown Manhattan, I learned about The Studio Yearbook of Decorative Art 1919, the bibliographic artifact of a Bauhaus-style initiative for the English countryside. The Studio Yearbook was the source material for this month’s Necromancers of the Public Domain, a quirky theatrical experiment from the Theater of the Apes company. Each month, the Apes, founded by married couple Ayun Halliday and Greg Kotis, “pluck a long forgotten volume from the shelves of the New York Society Library and resurrect it as a low budget variety show.” Previous picks have included Hints and Observations for Those Investigating the Phenomena of Spiritualism (1918) by W.J. Crawford Physical Training for Women by Japanese Methods (1904) by the un-Japanese non-woman H. Irving Hancock.

Participants and friends of the company are invited to peruse the month’s selection and put together an act inspired by the book as a whole, a section of it, a theme, or even just a sentence. One performer, the fearless Katharine Heller, developed an entire piece inspired by a single thumbnail illustration. Ayun Halliday, who also hosted, presented a fun collaborative work of internet art. Inspired by the exuberantly dismissive Tumblr Fuck Your Noguchi Coffee Table, she projected images from The Studio Yearbook with captions like “Fuck your utterly fabulous curtain material.” She ended her act with crowd-sourced material, asking friends to submit their most obnoxious bits of home-design with self-deprecating captions: “Fuck my husband’s Emmy” and “Fuck mon Le Corbusier chaise lounge.”

Illustration from The Studio Year Book of Decorative Art 1919, caption by Ayun Halliday.

The tyranny of elegance was a theme throughout the evening. Ellia Bisker with Heather Cole, wearing dresses shaped like houses but somehow still flattering, sang about the “right to be surrounded by class and good taste,” an aspiration that involves chucking souvenirs and tacky heirlooms. “Pick a color scheme,” they crooned, “and execute it mercilessly.” Bisker and Cole managed to be sarcastic without being cynical about the ethos of confronting destruction and squalor with beauty. This is an easy notion to mock, but it’s important to appreciate the fact that The Studio Yearbook was addressed primarily to the working-class and veterans returning from the war and relying on government relief. Melody Allegra Berger was delightful singing and fiddling, but I was let down by the derisive attitude in the refrain of her song, “I wanna live in a tiny cottage/Built by Big Brother just for me.” I doubt I was the only person in the audience who pays $1,000 to rent a single room, and who wishes our government provided housing that was not only affordable but beautiful.

For me, the most satisfying act of the night was Greg Kotis’ short play, in which he played a landlord with a cottage to rent and David Carl, returning to the stage after an earlier musical performance, as a possible tenant. The play was funny and meta-dramatic; the actors’ dialogue provided the sound effects as well as crucial information, like “I am speaking with an accent! This is England!” With lines like “I have shell-shock. Later it will be called battle fatigue and then PTSD,” it cheekily winked at historical retrospection, but, unlike some of the other acts, took none of it for granted. That’s because the play, though hilarious, had a real emotional core. Both characters were veterans, ravaged, like the landscape, by the war. As it nears its tragic denouement, the landlord says “Building cottages, it’s a nice gesture, but…” to which the potential tenant replies, “It’s a start.”

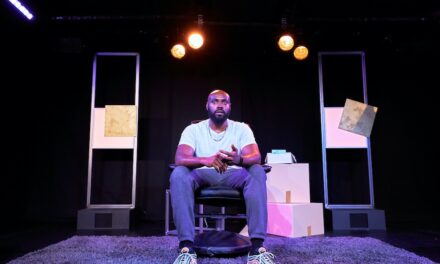

David Carl and Greg Kotis. Photo by Felicity Mckenna.

Admittedly, my critiques of some of the other performers’ cynicism are of limited efficacy, because each necromancing is a one-night-only show. Also – a bias: I spent the previous week at an academic conference devoted entirely to the history of 1919, so maybe I was a little too prickly for jokes about relief efforts. (It’s a weird feeling when you want to shout, “Too soon!” at jokes about something that’s literally 100 years old.) That being said, I respond best to earnestness. The Studio Yearbook performance took place the same day the Notre Dame Cathedral was ravaged by a fire. They couldn’t help that of course, but to scoff at the idea that beautiful spaces can, as the Yearbook has it, “contribute to the well-being of a community,” seemed a bit, well, tacky. That’s why Kotis’ play was my favorite. It took seriously the Yearbook’s intervention.

Ayun Halliday, known around here as the Chief Primatologist. Photo by Felicity Mckenna.

Like The Studio Yearbook, The Tank has a radical mission: removing the economic barriers to performance. They provide free rehearsal and performance space, plus publicity, and they keep ticket prices affordable, which is truly rare in New York. Necromancers of the Public Domain, too, is all about celebrating the accessible, and I love the form that celebration takes. At the end of the performance, Ayun announced it was time to “return the book to the vortex,” i.e. the library. These values are more than just decoration; they’re the very core of culture.

Necromancers of the Public Domain have their next two shows already organized. On May 13th, performers will riff on Childhood by Alice Meynell (1913) and June 17th is devoted to Laurette Taylor’s The Greatest of These (1918). Have a look and get inspired, not by an obsolete model of what once was, but as a vision of what could yet be.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.