In this time of superdiversity, with different cultures and strata of the population living alongside each other, how to make a performance that is potentially open to everybody? This inherently impossible question lies at the heart of Mount Tackle, a project by choreographer Heike Langsdorf. With this project, Langsdorf continues a movement that started from working in the public space (i.e. Postcards from the future, with the collective C&H), going beyond the threshold between public and semi-public space (i.e. Sitting with the body 24/7), to arrive at the theatre space. Throughout this journey, she collected insights and experience, taking them from the ‘outside’ into the theatre, in order to open it up from the inside.

This criterion of being ‘potentially open to everybody’ is not about creating a mainstream, easily consumable product. On the contrary, it involves an inquiry into what it means to transform the theatre into a radical, public space. What limits haunt the theatrical apparatus? Which cultural conventions are so deeply ingrained that the experienced theatre-goer and theatre-maker no longer notice them, but which nevertheless present an insurmountable obstacle to people with diverse socio-economic backgrounds? This question extends beyond the boundaries of the actual performance and implies the whole context, from the theatre building, over communication, to audience development. Let’s follow Langsdorf’s trajectory and think along from the outside to the inside, in an attempt to grasp this mountain.

Our path starts with the way Langsdorf and her collaborators communicate about the performance. Instead of using conceptual images or traditional theatre photography, a comic book style series of drawings (by Raquel Santana De Morais) depicts possible situations during the performance. Multi-language flyers and a brief, specific announcement on the website tell us what to expect: there are three parts, the audience can move around and “touch what is there or leave things alone” and after one hour of performance people are free to go in and out. These announcements do not include concepts, references to specific stories or themes and do not explain ‘what the performance about’; in short, they contain nothing that could steer the experience and interpretation beforehand. The same goes for the trailer (a short movie by Mathieu Hendrickx), which reflects possible sensorial experiences. This is the first example of a recurrent strategy in Mount Tackle, namely combining the concrete and the vague, in an attempt to create openness towards both new and existing audiences.

A newly discovered world

Upon entering the theatre, it soon becomes clear that theatre as a space with a separate stage and gallery has been rethought. The stage flows into the gallery and vice versa. Quite literally so: the scenography (in collaboration with Ief Spincemaille) has the stage spilling over into the seating area, as do the lighting and sound at specific moments. The audience can freely move around and is even invited to do so throughout the performance. Nevertheless, the stage area with the actual mountain remains the center of this newly created space. Perhaps environment is a better term to describe this situation; Langsdorf herself talks about conditions in which things can happen. The openness towards a diverse audience is translated into an open environment which, however, is not arbitrary, but rather allows each spectator to decide what to focus on and how to relate to the performative elements and the other spectators. Turning theatre into a public space implies a responsibility for your own position too.

The space of Mount Tackle is a theatre made public, but simultaneously a world in itself. This world initially resembles an installation. Almost completely built out of salvaged materials (small and not so small stuff, assemblages of colors, fabrics, books and bags), this world is reminiscent of a refugee camp, a landfill or a post-disaster area, but also of an ecological society or a colorful playground. Despite the more negative associations this space evokes, it isn’t sad or estranging, on the contrary: it definitely intrigues. It is the world with its own logic; a logic that only starts to make sense at certain times, only to be blurred again shortly after. The atypical, ungraspable collections fascinate and feel like something new: an alternative, full of potential. This is not a lost world, but a newly discovered world where we, the audience, are invited to play a co-constitutive role, already just be being there.

In Mount Tackle, children start to play and immediately invent their own world, while also engaging with the (more adult) audience members who walk around, explore the space, drink some coffee or eat a biscuit. Those who still feel a bit awkward at first are free to watch from the ‘safe,’ traditional position of the tribune, until they consciously decide to get up and take a closer look. This results in a continuous dynamics of approaching, zooming out and focusing on yourself or paying attention to others and the group to which you inevitably belong.

Open concentration

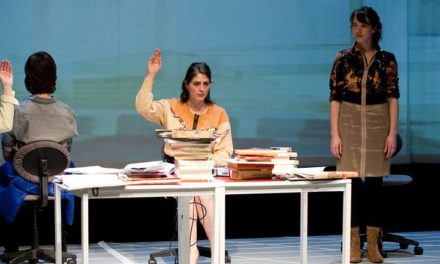

In this open environment, the audience’s attention is nevertheless subtly directed through several theatrical means. At a certain moment, small performative actions by Lilia Mestre start to develop: walking around, carrying stuff from one place to another, spreading hay or a duet with Langsdorf consisting of placing objects. These little performative gestures balance on the verge of invisibility. They also walk the tightrope between meaningfulness and meaninglessness. The principle of productive vagueness used in the communication is central to Mount Tackle’s performative core as well. Scenography, sound, light and performative acts offer numerous suggestions, without generating a unifying narrative.

The initial situation of ‘open concentration’ during the first performative actions gradually evolves into a more focused and detailed set of gestures. The light design (in collaboration with Michaël Janssens & Ief Spincemaille) follows the same trajectory: the introductory, open light, which is important to create the Mount Tackle environment that bridges the gap between stage and tribune, subsequently starts to zoom in on the performers’ increasingly small actions, hence guiding the audience’s attention. These actions involve objects, fabrics and other materials that are part of the set of onstage collections. The materiality of this ‘stuff’ is explored through its tactility and sonority.

A part of the ‘crowd’ gathers around these performances; others already initiate interesting actions for themselves, drawing their own crowd. Others are too far to see. The sound is their only connection to the events. Often, an action or the way a particular object is used appears to have a narrative function, only to continue for too long, thereby becoming a thing in itself. This ‘thing’, then, is often a sound quality, captured and amplified directly by sound artist David Helbich, who allows the audience to imagine what it cannot see.

In addition to light and performance, the sound is a central element in Mount Tackle, traveling along the same trajectory from outside to inside. In the first phase of the performance, the sound from outside seems to continue inside, reminding the audience of the hum of cars, airplanes, trams and buses or even construction work – in short, the noise of our busy, traffic-jammed cities. When the second, performative phase announces itself by way of the collapse of the mountain, a silence falls. Then a different sound arises. Little details like air currents, a footstep, giggles, or the sound of a toy are all registered by hypersensitive microphones. This environment invites us to listen. Numbed by the daily noise in our streets, our sensitivity to the musicality of the small, the subtle and the accidental has been diminished.

Listening is the red thread throughout this second phase. If we remember the tower of Babel, which collapsed when people could no longer understand each other, creating the condition and the demand to listen (in absence of any visual input) seems a reaction to this globalized miscommunication. However, whereas the collapse of Babel’s tower was a catastrophe, the collapse of the mountain in Mount Tackle offers a new beginning. In this environment, listening is more important than understanding. And perhaps this not only applies to the theatre, but to the world beyond its walls as well.

This performance does not consider participation as an inclusive project. Rather, it offers the possibility to become part of an environment, to find your place and role in a world that is open to your presence. Perhaps even more important, it creates an atmosphere in which not understanding is acceptable for the audience and even becomes a liberating experience. Mount Tackle doesn’t need the audience’s participation per se. The crux is precisely that, adding something of your own or being attentive to a gesture, a walk, a little game or a conversation can enrich your own experience as a spectator, just like it could do in everyday life. This is no soft ‘we are the world’ situation, but rather a complex task: not waiting to be told what to do, but taking initiative, in whatever way possible and using only your own happiness as a measure of success.

Patches

After this movement of zooming in – which actually started the minute the audience members decided to attend the performance, and which reaches its most intimate moment in the pitch black and during a high-sensitive sound ‘concert’ at the end of the second phase – there is a radical shift to a third development. The lights open up again, the concentration is lifted and we are now in what is perhaps an even more public place. Several other audience members turn out to be performers and start to execute actions. This time, their logic is not hidden: they are clearly cleaning, rearranging the space. This is a different kind of openness, one that allows everyone to freely participate and hang around, creating a relaxed, pleasant vibe. It seems like everyone needed the concentration to build up, then needed to let it go and unleash the tension, in order to feel the desire to actually ‘do’ something.

New islands of stuff appear, now clearly grouped by some characteristic: car parts, clothes, small objects, blankets, … everything is arranged in a more or less readable mode. After the deconstruction of the space, there is now a new ‘order’, one we can read and inhabit with confidence. Sounds remain present and are more richly amplified. They simply ‘are what they are’, no longer suggesting any narrative event. Someone is playing different kinds of pop tunes on his phone. Did our ears need the ‘training’ of the previous hour to enjoy this and to feel comfortable now?

Mount Tackle presents no linear performance, but rather a patchwork of situations. Some patches are created by Langsdorf & co, but others arise through the actions of the audience members and their positioning. Patches of focus, patches of stuff and junk (no garbage!) emerge and dissolve throughout the first two sections of the performance. The final part actively creates a patched order on stage.

Scholar Anna Löwenhaupt Tsing proposes patching as the conceptual alternative for linearity and a western-centered perspective on the world. After all, patching opens up new associations, liberated from causality, chronology and rationalist categories. The public space that unfolds in Mount Tackle, rethinks the ‘public’ as a patchwork of common things, gestures, and people. In this sense, patching is a way out of the traditional theater, where something is offered to a seated audience, or where participation is clearly delineated and prearranged. In this sense, diversity could be seen as a patchwork as well: there is no complete overview, there are no fixed categories to make things manageable and completely understandable. Perhaps what is told to the audience upon entering the theater suggests the perfect motto for a patched way of being in the world: there is no ideal spot, so we invite you to try different perspectives.

Kristof van Baarle is working at Ghent University on a doctorate on posthumanism in the performing arts. He acts as a dramaturge for Kris Verdonck – A Two Dogs Company and also collaborated on Heike Langdorf’s Mount Tackle

Originally Published on www.open-frames.net. Republished with kind permission of the author.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kristof Van Baarle.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.