As the darkness creeps in, the already crowded plaza in front of the National Taichung Theater attracts some unexpectedly haunting visitors. Ghosts from different eras of Taiwanese history begin to flow into the noisy crowd, creating an eerie but serene atmosphere. These are some faded but not forgotten figures, including Dutch businessmen, English missionaries, native tribal Taiwanese, Japanese geishas, among others, representing the collective memories of this traumatized and more-than-once-colonized island. The wanderers, in between life and death, are summoned. A bunch of Fu, yellow letters of ritual symbols that often relate to Taoism, are attached to the main entrance of the theater. Next, Zhong Kui (who is like a Chinese ghostbuster) appears heroically with his fellow assistants. He strides towards the main entrance, accompanied by drums while drawing Fu in the air and spitting water from his mouth (洒淨, namely water purification). The goal is to ritualize the space and time and prepare for the ceremony that is about to follow. The Fu on the entrance is then cut, and Zhong Kui enters the theater with all the ghosts and the audience following behind.

Pure. Water. is a series of performances, dances, installations, and community-based events curated by Chiu Kun-Liang, a writer and professor, who specializes in traditional theatre arts and rites in Taiwan, to celebrate the inauguration of the National Taichung Theater (NTT) in August 2016. The building was designed by the esteemed Japanese architect Toyo Ito, and it features an expansive, intertwined and curved structural design. It is an architectural wonder that attracted vast attention, both international and local, even before its completion. Now it is a vital and buzzing venue in Taiwan, harboring local and international operas and performances.

Pure. Water. was inspired by traditional ritual practices in Taiwan, fueled by both Taoism and Buddhism, and contemporary theater and dance aesthetics. August is, coincidentally, the “Ghost Month” in the Chinese lunar year, and many rites take place in temples and homes during the Chungyuan Festival. It is believed that the “gate” to the other side of the world will be open during this particular time, and that the dead wanderers will walk among living beings. It is a time when people show their respect for their ancestors by performing a variety of rituals to satisfy and pacify the ghosts and politely asking them to return to where they belong. A feast is an essential part of the ceremony, where hungry ghosts can munch on some delicious ‘earthly’ food unavailable to their world.

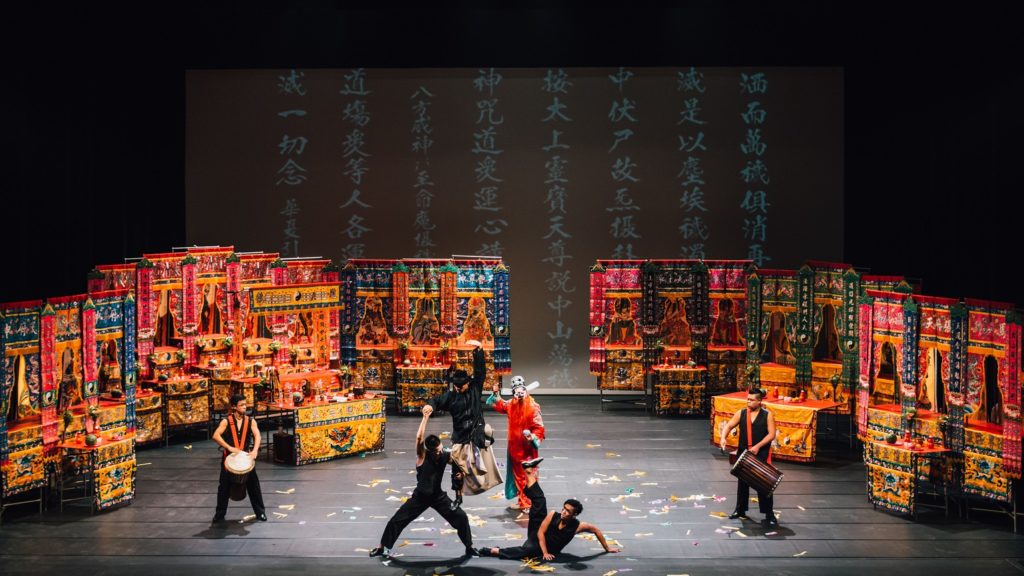

The main concept of Pure.Water. is “醮祭”—Jiao Rite—a ritual practice that comes with a variety of forms and purposes such as the celebration of new temples. A month before the series began, the theater built a long, tall pole with a lantern on top (豎燈篙—which literally means erecting the pole light). The purpose of it in Jiao Rite is to attract and invite ghosts from every direction. Seven traditional ritual spaces scattered around the theater, such as the “Han-Lin Temple (翰林院)” (where ghosts rest during the festival), were reconstructed and reinterpreted using modern metal materials by the architect Jiang Yue-Jing. The main Jiao platform was erected for multiple purposes, blurring the line between tradition and innovation, ritual and theatre. As Chiu explains, “It is a ritual space, a performative stage, a place where we interact with audiences.” The invitation the lantern light sends out is not just for ghosts, but for a wide range of audiences and local communities. The gate is not just between life and death, but is the epitome of opening up the dialogue and interaction between high-end opera and performing arts, and grassroots, diverse cultures rooted in the soil and water of the island.

After Zhong Ku ushers the audiences into the house, an immersive, ritualistic dance performance (choreographed by Hou XiaoMai) takes over. The dancers (featuring all the ghosts) move throughout the building and hallways, in between the main opera house and other, smaller theaters. It is like an intimate tour to help the public get to know the theater through the lens of Taiwanese traditions and history enacted and interpreted by dancers’ bodies and souls, twisting the time and space. A visceral, profound way to demonstrate how a theater takes responsibility for continuing the old and new and bridging the past and now.

The audiences then convene at the main opera house, witnessing the main rite “Chilly Forest Feast (寒林宴).” After a fire dance (fire and water are the two most important elements in a Jiao Rite), two fellows of Zhong Ku appear on the stage and in the auditorium, performing a theatricalized, physicalized version of “洒淨” (spitting water from their mouths to purify and neutralize the space and spirits). The curator takes advantage of the rich theatricality embedded in Taiwanese ritual practices, distilling its symbols and meanings to reflect on the perpetual values of theatre-making. Then, the back door of the theater opens—audiences in the theater and audiences outside face each other, forming an amphitheater. The dancers usher audiences in the theater to walk outside. Xuanzang, a Buddhism canonical figure, appears and performs the ritual gestures of pacification and purification, completing the performance of Chilly Forest Feast. The whole series concludes with a “mannequin drama (跳嘉禮)” performed by real shamans.

Pure. Water. is a milestone in Taiwanese theatre history that celebrates cultural diversity and roots in an epic but equally genuine and heartwarming approach. It doesn’t just re-appropriate traditions and religions for some superficial symbols and slapstick effects. On the contrary, it shows a deep respect for the spiritual side of the daily lives of Taiwanese, and a heartfelt commitment to reach out to all the communities across the nation. It also embodies what Jean Genet believed in: “The work of art is not destined for the subsequent generations. It is offered to the innumerable mass of the dead.”

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kai-Chieh Tu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.