The WaxFactory’s new production Lulu XX is many steps away from originality. The heart of the play is Lulu, a figure created by the German playwright Frank Wedekind for his plays Earth Spirit (1895) and Pandora’s Box (1904). WaxFactory co-founders Ivan Talijancic and Erika Latta drew on this source material in 1999 when they presented their first formal collaboration, Lulu. The current iteration, which puts Wedekind’s work in a blender with sources as disparate as Nietzsche and Eartha Kitt, seeks to reexamine womanhood as a construct and, I suppose, as an experience. Unfortunately, Lulu never quite comes to life as anything more than a receptacle. The fact that this same critique can be leveled at Wedekind’s almost 125-year-old work makes one wonder what Talijancic and Latta are trying to accomplish with this show.

The good: Erika Latta gives a strong and spirited performance as Lulu. Two stagehands, credited as “stage magicians,” appear onstage to aid her with props, but this is essentially a one-woman show, and Latta carries it with powerful energy. Her physical strength is astonishing as she dominates a drastically raked stage in Louboutins so high, it hurts to look at them. When she stalks upstage, she looks as colossal and commanding as an Amazon. The design is also quite impressive, including Miodrag Guberinic’s costuming and the multimedia projections for which WaxFactory is known. The stage is flanked by three white walls which screen footage to signal shifts among the nine vignettes that make up the show. The displays range from animation to city scenes to film clips (from G.W. Pabst’s adaptation of Pandora’s Box, I think) and scenes of Latta in other contexts. The integration of live performance with filmed media was smooth and effective.

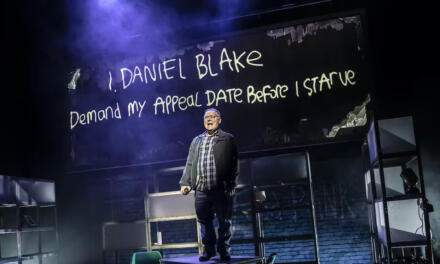

Photo by Tasja Keetman

The less good: some of the lighting was nothing short of aggressive. During a sequence in which Latta is repeatedly photographed, the flash effect was relentless. Presumably, this was symbolic of the destructive power of the male gaze, but I had to close my eyes, causing me to miss most of the scene, and they still hurt for a long time after. The script was also very uneven. Again, we can chalk this up to symbolic representation. Wedekind’s Lulu is essentially defined by other people’s use of her, and she becomes the sum total of her experiences without a stable core identity. She’s a kind of Frankenwoman. In German expressionist theater, we may say this accounts for her mystique. But this much meaning has been squeezed out of Lulu for long enough. Can she have a self already?

Photo by Tasja Keetman

The larger issue is that the play seems inadequate to its own ambitions. According to the show notes available on the WaxFactory website, this production “challenges the idolatry and misogyny of the male gaze in artistic representation of women, exposing its conflicting tendencies. Inspired by the momentum of feminist protest, we revisit the unapologetic heroine, asking new questions about agency, representation, and violence in the contemporary world.” But actually, the show is dated. Feminist discourse and debates around agency, but more importantly power, have advanced a great deal in the past twenty years. The titular XX refers to that time period, but it also evokes ratings of sex in media. The fact is, this Lulu, twenty years older than her predecessor, has no agency. Watching her cycle through archetypes – a femme fatale, a sex kitten, a murder victim – is a rehashing of old stereotypes and a waste of Latta’s considerable talent. Maybe Lulu could work for the #MeToo 21st century, but she needs to be transformed not into a conglomeration of different texts and multimedia inputs, but into a person.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.