Ken Loach’s 2016 film I, Daniel Blake is a scathing indictment of the British benefits system. The film follows 59-year-old widower Daniel Blake who suffers a heart attack and becomes unable to work. Despite medical evidence and GP support, Blake is told that he is not eligible to receive state benefits.

The film powerfully shows how the knotty bureaucracy of the benefits system robs claimants of their humanity and reduces them to a number. The story has been powerfully adapted and updated for the stage by the film’s star Dave Johns to show how the cost of living crisis has worsened what was already bad in 2016.

As Johns says: “The story is still as relevant as it was in 2016; maybe even more so now … [Daniel’s] story could be anyone’s.”

The character of Daniel Blake is fictional. However, the stage production features real speeches, factual interviews, and social media posts. This molding of fact and fiction humanizes a group of people who are so often robbed of their dignity in the headlines and in politics.

Staging reality

When serving as secretary of state for work and pensions in 2016, Damian Green MP branded the film version of I, Daniel Blake “a work of fiction”. The play responds powerfully to this dismissal by projecting the words “THIS IS NOT FICTION” across the stage. The production forcefully shows that people really have to live like this.

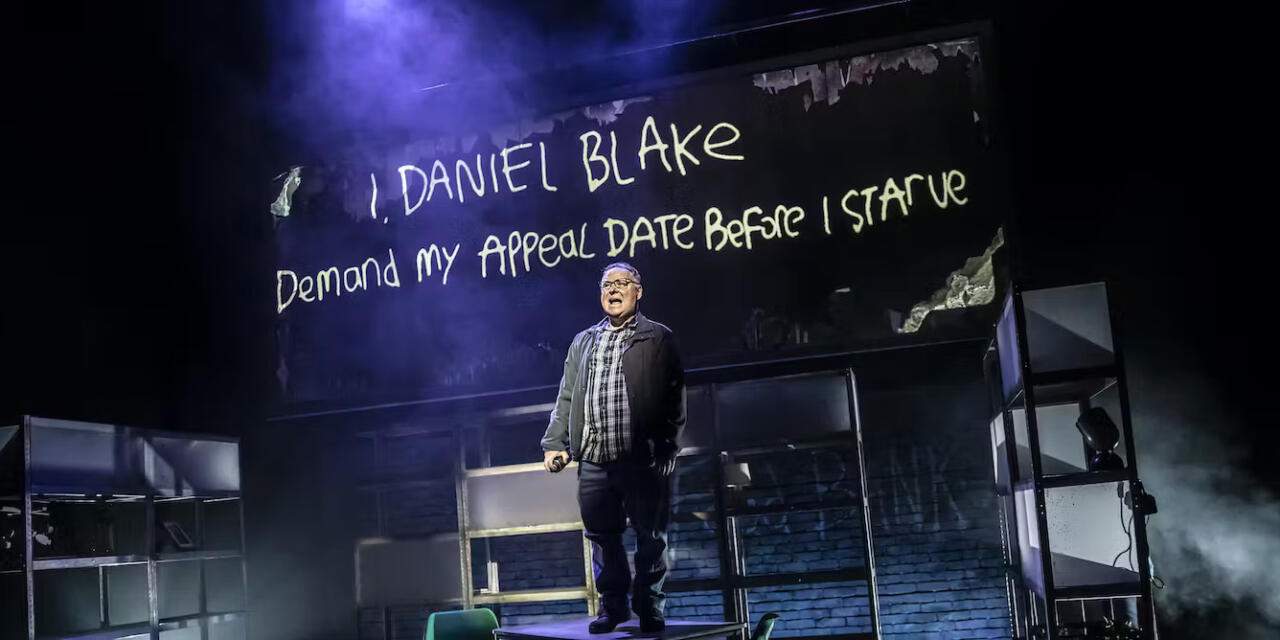

As Daniel Blake puts it in a spray-painted message on the wall of his Jobcentre, “I, Daniel Blake, demand my appeal date before I starve.” The poverty rate for families on universal credit stands at 54%. This explodes the myth that benefits claimants are “scroungers,” with a breezy lifestyle funded by the working UK taxpayer.

The use of real political snippets demonstrates the gap between the UK government’s policy objectives to boost wages and get more people back in work and their detrimental effect on real lives.

According to a 2022 report from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 14.5 million people in the UK live in poverty. The 2023 report warns that because benefit payments have failed to sufficiently increase in alignment with rising inflation, the UK’s poorest households have become even more vulnerable.

Crucially, the play destabilizes the notion that the UK welfare system can act as a “safety net” should any of us fall on hard times.

Blake (David Nellist) has never sought state support before and his failure to be awarded sufficient points at his work capability assessment comes as a shock. As well as depicting the pinballing nature of the benefits system (at both the claiming and appeal stages) as Blake is sent from one interview to another, the production implicitly satirizes an approach that reduces the complexity of human lives to a set of points-based descriptors.

Audiences see how anyone completing a work capability assessment must explain how their illness or disability affects their completion of a list of set activities. The more difficult you find that activity, the more points you might get.

Political theater

Alongside the fictional Daniel Blake’s story are the words and stories of real individuals, which is a technique central to documentary or “verbatim theater”. These are projected behind the actors to make it clear that this story is grounded in the lived experiences of many.

Documentary theater often tells real stories. Here, however, they have decided to tell the story of the benefits system through a fictional character.

The phenomenon of “infrahumanization,” Coined by the psychologist Jacques-Philippe Leyens, occurs when certain groups in society (such as benefit claimants) can be seen as less than, or “below” human.

The words of real people are projected throughout the performance behind the actors to make it clear that the story is grounded in real experiences. Pamela Raith Photography

The American philosopher Martha Nussbaum argues that fictional representations can cut through the biases people hold in public discourse. These stories become vital to ensuring we live in a just and democratic society.

By weaving the fabric of non-fiction through a personable, ordinary character, I, Daniel Blake draws visceral attention to the human cost of such precarious living.

This production humanizes the people behind the headlines. It spotlights the hurdles that the most vulnerable citizens face in realizing their basic right to human dignity in the UK’s benefits system.

In this way, I, Daniel Blake demonstrates how theater can campaign for social justice and hold the government to account. Johns hopes that it will make people angry, generate discussion and keep the cost of living crisis on the news agenda.

The play will complete its initial Newcastle run before embarking on a nine-venue UK tour. Wherever it travels, I, Daniel Blake’s unique combination of black humor and sobering facts will seek to reclaim the personal narratives of those on the breadline. Crucially, it is only by doing so that it can pave the way for reform.

This article was originally published by The Conversation (https://theconversation.com/us). Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sarah-Jane Coyle.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.