A transpersonal and transcultural desire to dance together

EXÓTICA is a journey that sets off even before the show proper starts. In my rush through its arcades, the Royal Saint-Hubert Galleries become a zoetrope of chocolate shops, gift boutiques, and chic restaurants–a parade of taste tourism that mindlessly reiterates the colonial accumulation and display of riches. In that sense, the premiere of Chilean-Mexican-Austrian based artist Amanda Piña’s latest piece at the Théâtre Royal des Galeries feels site-responsive. EXÓTICA beckons its audiences to examine the productions and consumptions of coloniality as it manifests between the dancing and spectating bodies across ethnic and sexual asymmetries. I enter the foyer covered with red velvet and mirrors, with the soundscape of tropical forests layered beneath the noise of the crowd. I can’t resist the feeling of being moved by some tingle that our predicament has deprived us of more and more: Fascination.

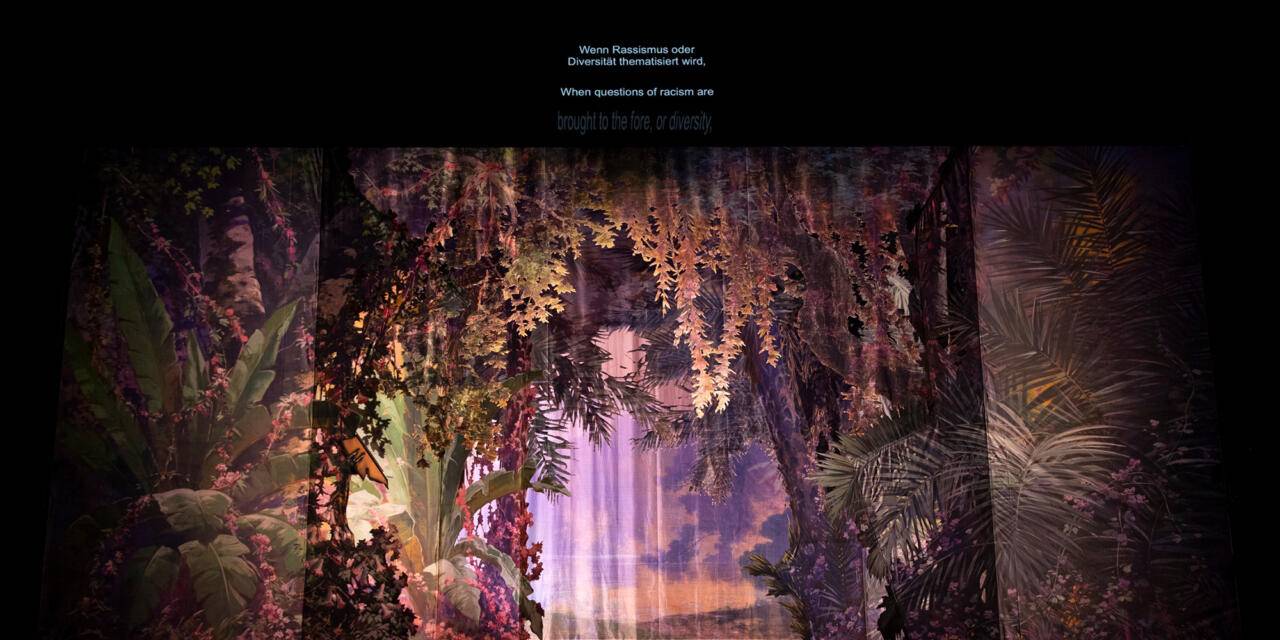

Piña rests EXÓTICA over multiple, interrelated dilemmas: We are presented with meticulous research on the notations and images of the fin de siècle dances by French-Indian choreographer Nyota Inyoka, Senegalese François Féral Benga, Kurdish-Ottoman Leyla Bederkhan, and Mexican Clemencia Piña “La Sarabia,” as presented and recorded on European stages. Standing tall under the centennial sylvan décor by Albert Dubosq, Piña underlines that this is a compossession—not a re-enactment for education purposes, but a re-enchantment that demands the audience to be present and spiritually engaged. On the one hand she wants to inject her audience with criticality about the intercultural legacies of dance history. She does this through her opening speech that indicates how the Western canon burned the evidence of its anxiety of influence. On the other hand, she wishes to revitalize the power of these motions as a form of decolonial reparation. She holds her audience accountable for the weight of that history in the present moment, while also inviting them to be intimate with their own ancestors.

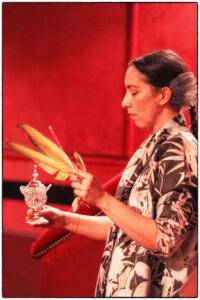

Piña gives reflective voices to her collaborators as well and enables them to dwell in their own ‘double consciousness.’ Border-crossing artists as they are, Venuri Perera, André Bared Kabangu Bakambay, iSaAc Espinoza Hidrobo, and Ángela Muñoz Martínez intersperse their personal admirations and debates around each dance pioneer they channel.1 In particular, the first letter addressed to Inyoka sets the tone in these otherworldly conversations. Sri Lankan artist Perera negotiates her unease with the identification of Inyoka as an “Indian dancer,” and questions the authenticity of Inyoka’s movements that in fact bear no classical code. At the same time, Perera reveals her tearful commiseration with Inyoka’s legacy, and appreciates such a courageous self-making to navigate a nascent international art-entertainment market that profited from difference without a real effort to comprehend it.

“At the core of the white gaze, I intuit a guilt-ridden love that exceeds the calculative logic of devouring and dismissing novelty. I suspect that the durability and introspection of this love may hold the key for a transpersonal and transcultural desire to dance together and dare each other in new rhythms.”

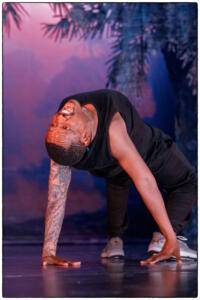

As the performance unfolds, the dancers’ discourses grow less inquisitive of the choreographic fidelity and more sympathetic with the resilience of these heroic personages. The dances themselves, on the other hand, progressively mirror each other in performativity if not in exact shape. The pelvic thrusts, shakes and shimmies, serpentine arms, and fluid spinal waves index the vocabulary of these graceful corporeal monologues. The piece segues from one artist to the next, separated by group dances set to the high energy of reggaeton songs composed by Piña with lyrics decrying capitalism. They seem to have a votive function to resurrect these dance ancestors by inviting them into contemporary dancehall gestures. Watching the performers cheer and embolden each other in these dance circles was pleasant. Yet the spiritual success of the cypher depends so much on the audience’s release into its exhilaration, which felt lacking in the premiere night.

© Patrick Van Vlerken

On a discursive level, EXÓTICA revisits several contentions of theatre and dance history, such as the contested authorizations of cultural identity and ownership in the face of globalization (Rustom Bharucha), the catch-22 of the artists of African diaspora between representing traditional beats and making modern choreographies of their own (Susan Manning), or the ambivalent force of white/colonizing gaze in interpellating, circulating, appropriating, and metabolizing otherness as a push for its own creative impasses (SanSan Kwan). Though I cannot dive deeper into these discussions here, I am amazed and grateful that EXÓTICA provides us with a chance to return to these crucial and still-current conundrums. However, at the point of dancing and embodiment itself, Piña’s aims seem opaquer. Except for Perera’s visible joy and investment in her solos, it was difficult to surrender to the magnetism of the well-curated bodies in front of me—though I must insist I speak quite subjectively from my own double-view. Despite their self-fashioning, I could not forget that these dance excerpts were never ritual dances but crafted or presented as variety pieces for popular entertainment. More viscerally, the clinical distance between the dancers and the dance was hard to ignore, which obliterated Piña’s will to transcendence. Such is the distance that suspends any affective or ethical contradiction that EXÓTICA might have purposefully mobilized.

© Patrick Van Vlerken

This brings me to a more fundamental question about the injustice narrative we are presented with in the beginning, which declares that these artists of color were hurt twice—once living and once after death. I wonder if we can further complicate the distribution of roles and intents. These choreographers found unconventional pathways to dedicate themselves to their art in collaboration with fellow gifted and errant souls. Even though they had to breach symbolic and material fortresses, they were unambiguously drawn to the magnifying glass of the Western concert stage. Who knows if and why they preferred that to the more lateral and collective installing of dance in the non-Western contexts? On the flipside, the new technology of camera at the turn of the century was particularly fond of the exotic, charismatic, graceful figures and movements of non-European artists. They were not properly remunerated or revered for their artistry, but they did hold a special attention in the visual archives of the Empire. Admitting these agencies requires me to give credence to, why not, a mutual fascination. At the core of that white gaze, I intuit a guilt-ridden love that exceeds the calculative logic of devouring and dismissing novelty. I suspect that the durability and introspection of this love may hold the key for a transpersonal and transcultural desire to dance together and dare each other in new rhythms.

As a working proof of this wishful thought, I would like to depart with a contemporary analogue to the four choreographers EXÓTICA reincarnates. Popular culture has long been at the forefront of consummating such passion for other, nonnormative bodies and movements. I think of dance studios like Millenium Dance Complex, founded in the 1990s and built a worldwide fanbase with the possibilities of 21st century new media. Without discrediting Piña’s timely cultural analysis, examples like MDC suggest that we can come to terms with the inexhaustible and democratizing impulse to show and watch outlandish bodies. We can also reserve a possibility for the subalternness of dance production and reception itself, the virality of which resists objectification even at its most commercial. Besides, the late 19th century European stages were not sparing their own imagined pasts and roots from loot, if one thinks of Wagner, Nijinsky, or Duncan.

Once again, the mutual fascination (between the dancer and the spectator, the West and the “rest”) opened by the voyeuristic relay of camera is not simply a peripheral factor in the cultural-political entanglement EXÓTICA sets to resolve. One just needs to pay attention to the fact that the choreographic logic of Piña’s excerpts is almost never about changing the location of body in time and space, but rather using the volume of the body itself to create expression, planted at the dead center of the stage/frame. The original dances were likely created so that the early film technology was able to catch up—not unlike the popular dances of today whose orientation is not solely the live audience in the round but more so the transfixed stare of the lens. Who are we to claim that the amateur or professional dancers of color are exposing and exploiting their sources mindlessly, or betraying a genuine identity that must be protected against the ocular capture? After all, each YouTube video of the MDC is backgrounded by a red wall with bold black puntos proclaiming “Unity in Diversity.” I wish Piña and her company have similarly basked in their ferocity and kinesthetic impetus. For EXÓTICA shuns that transformative fascination while it solicited empathy from the Kunstenfestivaldesarts audience, caged as it was in a secular temple arched by the imperial coat of arms, “L’union fait la force.”

1 Although Martínez’s speech had to be skipped in the premiere night, it is part of the score.

This article was originally published by Etcetera (https://e-tcetera.be/). Reposted with permission. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Eylül Fidan Akıncı.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.