Love seems to have preoccupied the planning team of the 2019/2020 season: it rushes on stage in so many variations and thematic lines that it is difficult to choose which one to favor. On the other hand, if it is one of the main themes that have occupied the humanity for centuries, then the Royal Opera House has just decided to draw on that output and has chosen three operas from various periods of musical history that deal with love, scrutinize love, analyze love and laugh at love. It was for the audiences to decide which aspect of that feeling, and which way to speak about it, was the most appealing and the most vital for a modern public. I also made my choice and will try to go from the least successful (in my view) to the most, to unravel what worked, and what did not, in each of the three operas that were on the ROH calendar during September 2019: Massenet’s Werther (1892), Mozart’s Don Giovanni (1787) and Handel’s Agrippina (1709).

Werther is the third revival of Benoît Jacquot’s production from 2004 – the previous one, as well as the premiere was conducted by Antonio Pappano, while this one featured Edward Gardner, who did the job magnificently. It was actually the orchestral work that was the most vibrant during the evening, bringing the nuances and emotional amplitude where the staging seemed to emphasize the pathos and unstoppable energy rather than the delicacy of a love feeling. Maybe it was not only the director’s fault – Massenet’s librettists have taken a number of liberties with the plot of Goethe’s novel, changing its crux – the unrequited love – to a love that is mutual but unrealized and subdued due to social expectations. With the development of Massenet’s opera, the challenge for a modern viewer is to understand why Charlotte doesn’t choose Johann in the first place: she is engaged to Albert only as a bow to her mother’s will, and this is the only string that brings about the following tragedy. Mutual affection is clear, Werther is never avoided, his love expresses itself in bold strokes (long stares, a constant presence, arias of love, etc.). His flight is an attempt to flee and forget, but obviously nobody does, and the final two acts are where the real emotions come to the surface (again, not with many nuances, but in a straightforward fashion), the pair of lovers quickly recognize their feelings towards one another, and Charlotte finally admits this love at the moment of Werther’s death. It is not really Goethe’s Werther, but something rather melodramatic in its attempt to show the human struggle between the socially accepted and the self-denied feelings. In some way, these two lovers could have been Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande: two operas share the rare genre – ‘Drame Lyrique’ – and even have vague similarities in the formation of a love triangle. But they are far from the same, as their feelings are too mature and the purity of Debussy’s lovers is delegated here to Charlotte’s sister Sophie and her other siblings that begin and finish the opera with lieder and carols.

The direction of Benoît Jacquot is in a way minimalist, leaving space for the singers and the music, and only intensifies in the last two acts, bringing forth the characters’ suppressed emotions. Charles Edwards’ set and lighting design try to show the contrast between the idyllic openness and colorful sunsets of the first two acts, when hope was still possible and human hearts were innocent and free, and the two last ones where bourgeois surroundings have stifled emotions that still try to break through. There is a moon where Massenet intended it, there is a scene with sharing bread, there is a wall with ivy hinting on pastoral beauty where love flourishes, and there is a small room where Werther dies, with Charlotte leaning over him. Goethe’s unrequited love would have been far more rewarding on stage, so one wonders why Massenet’s librettists Blau, Milliet, and Hartmann went for such simplification in the hope of portraying romantic love. As it is, even intended contrasts are too straightforward in this opera, with nothing triggering a modern appetite for intricacy and details, and thus one must turn attention to performance and music to find them.

Isabel Leonard as Charlotte in Werther, ROH 2019. Photographed by Catherine Ashmore.

Here Juan Diego Flórez singing the leading role should have been the highlight of the production, and he definitely tries to be. His acting is good, though still abiding by that simplistic pathos of tormented love that Jacquot chooses, his different costumes (Christian Gasc) are fitting the general color scheme of the production, as well as marking him a dynamic center of the action. However, his voice is not very strong, and though it accentuates Massenet’s phrasing with care and much fervor, somehow in many instances it just doesn’t come across. Isabel Leonard as Charlotte is much more powerful in her delivery and complements her tragic lover very well, accentuating how passion fights with purity in her heart. She also convincingly shows the transition from a pure girl to a matron who still has her secret locked away. A very nice discovery of the opera is Heather Engebretson’s Sophie, whose vocal lines are sometimes much more demanding than those of Leonard’s. She also diluted the generally static nature of the protagonists’ movements with her swift and alert presence. Children’s voices are always a pleasure to hear, while other parts, even that of The Bailli (Alastair Miles) somehow blur in one’s memory after the show.

It was actually immensely rewarding to sacrifice one’s seat in the stalls for a side-view to see Edward Gardner conducting and I must confess I forgot to look at the stage during the second half, as all the drama missing on stage was in fact there, with Gardner, having his own love affair with the orchestra and voyaging through the score with such energy and dedication. He should have been on stage for us to see the dramatic potential of Massenet’s music that was not truly acknowledged by the creative team. It was a truly fine work from LPO’s future Principal Conductor, and indeed the raison d’être of this particular ROH performance.

Mozart and Da Ponte’s Don Giovanni at Covent Garden was also the third revival of an original production by Kasper Holten, the latest one being in 2018, with Marc Minkowski conducting. This time Mozart’s opera buffa was conducted by Hartmut Haenchen, and from the start, with its impressive set design by Es Devlin, the production had a nice vibe of modernity and innovation. While Werther was built around a couple of lovers struggling and falling under societal expectations, this production shows someone reveling in rebelling against them (Revelling and seemingly getting retribution, as we expect from the plot). But here, Karsent offers us an interesting tongue-in-cheek sensation in actually making us doubt whether Don Giovanni deserves the blame showered on him for centuries. The opera cannot diverge into an entirely new direction and faithfully present us with all the scenes of seduction (Donna Anna, Donna Elvira as a present memory of the past, and Zerlina as the current interest) or an act of final infernal revenge in Commendatore’s arrival. However, we get the feeling that Don Giovanni is someone who is the victim of stringent puritanical societal rules, while actually, Dionysus-like, fertilizing the world and blessing it with endless invention and change. If it wasn’t for Don Giovanni, always ready to adapt (reflected in Mozart’s music, where he borrows his musical lines from his partners) and always appreciative of women’s beauty, would the world even exist, would the stage move?

Don Giovanni at the Royal Opera House, September 2019. Photographed by Mark Douet.

And indeed, the stage is a constantly changing cube that is gradually covered (with very inventive video design from Luke Halls) by white splashings of human handwriting – which turn out to be lists of female names. They are there to illustrate a famous Leporello’s Catalogue Aria (“Madamina, il catalogo è questo”) about thousands, hundreds and dozens of conquered women in different countries, including Turkey. They would appear on the cube again and again – coinciding with new ideas of conquests proposed by Don Giovanni, but also as a kind of moral warning, as later on in the opera these names would be covered in big (video) bloodstains. They also re-appear in blue and purple, in black, like the reminders that one’s consciences send to one’s brain. Sometimes one wonders whether the creative team was too obsessed with them in a way that Don Giovanni would not be. Interestingly, moral reminders (real or satirical) are even ingrained in the costumes (Anja Vang Kragh) – for instance, Donna Anna’s dress develops a grey splash over its pink as a sign of contaminated virginity. In a way, contamination (Don Giovanni being the source of it) is the key element of video and set design, as the whole cube is occasionally covered with spots and splashes of color, while female figures silently watching over Don Giovanni become invisible through being filled by white or black colors. Thus, in this production, a set of messages is being actively portrayed parallel to what is going on stage.

Does it help us to listen to Mozart’s opera? In a way no, as, while drawing all our attention, it massively distracts from the music later on. Also, it feels like the singers struggle to find their place inside, or in front of, the set construction. The set lives its own life, almost becoming a piece of artificial intelligence with its vengeful innuendos incorporated into the opera and it is difficult to try and focus on the singers. And it’s a shame, as Erwin Schrott is quite remarkable both as an actor (a tireless Don Giovanni character) and an outstandingly versatile singer. He is so energetic and appealing that he does everything to persuade us that if Don Giovanni did not exist, he should have been invented because the world (even if morally correct) would be a boring place without him. Louise Adler (Zerlina), Myrtò Papatanasiu (Donna Elvira) and Malin Byström (Donna Anna) do an incredible job of presenting different female characters and their respective bouquets of emotions towards him (revenge, jealousy, admiration, retribution, skillful deceit). Roberto Tagliavini does a good job serving as the comical counterpart and partner (Leporello), and Daniel Behle (Don Ottavio) and Leon Košavić (Masetto) have their turn for nice singing and public applause. However, with the set living its own complicated life full of splashes of color, bolts of thunder, lightning, blood stains and Don Giovanni’s conquest lists (a bit repetitive by the end), the stage action became slightly stagnated, turning into a Commedia dell Arte string of quid pro quos and mistaken identities. I am not sure that a mismatch between the set and the singing/acting is what the director intended, but that was what partially happened, leaving a mixed impression. The message, of which there were multiple, conceived as a rebellion against social mores, was not restated or lost in a continuous whirl of moving cubes. One was left with a liberating feeling that the love engine (even in its semi-Pan, semi-Zeus version) is still there somewhere, even if it only exists in the world’s attempts at mythologizing virility.

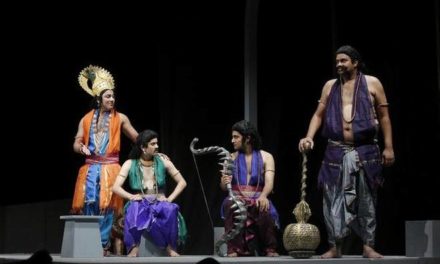

And the third story of love – and power – was Handel’s Agrippina. The opera had its premiere at Royal Opera House, having been transferred from the Bavarian State Opera where it was shown earlier in 2019. It was the first London production to be sung in original Italian 310 years after the performance in Venice. The professional productions in London (Kent Opera at Sadler’s Wells in 1982, ENO in 2007, and English Touring Opera at Brittten Theatre (RCM) in 2013) were all in English. It was also performed with the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment and thus on authentic instruments of the period, with musicians being led by a Russian conductor/harpsichord player Maxim Emelyaniychev. It would seem that with such an approach, the opera on stage would be cast in period-costumes and static arias revealing Handel’s beautiful music, but the plot (libretto attributed to Vincenzo Grimani) does not allow that, as it is as sparkling and adventurous as the latest criminal TV series. In Barrie Kosky’s inventive and outrageously funny production, the opera becomes a modern take on what it is to be thwarted in one’s ambitions, how one woman can outfool another, and on how the ambiguities of human pretense are driven by hidden passions and desires. These emotions, and character’s deeds caused by them, succeed each other in a whirl of happenings, while Handelian music – still poignant, powerful, lyrical, outstanding, and fresh – brings tears to our eyes. The paradox of this period/modern combination, the set and directorial decisions bringing out the best in the singers (what a cast has been gathered) and the orchestra (a unique, world-renowned ensemble) were the true success and triumphs of this Agrippina.

Multiple plotlines involving a desire for female flesh and a desire for power in the best Roman tradition, (but without the blood being drawn or the big tragedies of unrequited love) are the crux of Haendel’s opera. It – especially in Kosky’s scenic realization – reminds us not of Racine or Corneille, but brings us to French farcical tradition like Beaumarchais’ Le Mariage de Figaro (the scene where Poppea hides her respective lovers under different pieces of furniture seems to be a direct quote from the scene with Suzanna and Count Almaviva) and George Feydeaux’s farces of love, plottings and outrageous fun. The set (Rebecca Ringst, with lighting by Joachim Klein) is a big, perpendicular structure with two levels that become either a set of lit rooms (for a scene with first visits to Poppea), a row of corridors where Agrippina’s scheming designs are undertaken, a podium for announcement of Claudio’s return, a large staircase leading to heaven, the triumph of power or, opening up, a large apartment of Poppea’s filled with sofas, couches and stools. It is devilishly multi-functional but never intervenes with the singers’ presence. It also sometimes almost disappears into the background, leaving the stage bare and allowing us to see interactions and hear the areas of all individual singers.

Kosky’s direction is also constantly serving the double goal: to make the audiences figure out and revel in all the intricacies going on, and at the same time appreciate each individual character in their specificity of action and emotion. Thus, Agrippina, sung by magnificent Joyce di Donato, has multiple occasions both to get entrenched in the web of scheming that she had initiated (she eavesdrops and waits at doors and hides in corners), and to steps into the limelight of the stage (on one occasion directly, as though she was a pop star) to have her rounds of applause both as an actor and a singer. The same goes for Poppea (Lucy Crowe, who is beloved by ROH audiences) who changes her attires (costume designer – Klaus Bruns) endlessly and in the end features a beautiful yellow gown drawing attention both of all male characters and of the audiences. She runs, she plots, she stoops to conquer, but she also sings her beautiful areas about love, revenge, and reconciliation with her adored Ottone (Iestyn Davies). His nobility is a pearl in the operatic turmoil that is Agrippina and he closes the first act alone on stage as he asks all of us what is he to do since the world has let him down.

Agrippina, ROH Covent Garden, 2019. Photographed by Bill Cooper.

Thus, the 18thcentury style of connection between the singers and their admirers (us) is preserved and not hindered by modern clothes, lots of running and plotting, or– and Kosky is not afraid of pushing the envelope here – lying down, pulling clothes off, hiding, panting, kneeling, etc. We also discover, with admiration and respect, that it doesn’t affect the quality of singing in this production. What Kosky does is to bring Handelian characters close to home – thus, Nerone (Franco Fagioli) becomes an infantile, almost teenager-like character in sneakers and a hoodie who can be manipulated easily into everything, but whose mental distress hints of an unstable Caligula-like adult who is prone to catastrophes. The only minor drawback is that possibly love itself becomes slightly shallow in all the explosiveness of action, but it still wins over, together with Agrippina’s lust for power Almost everyone is paradoxically (and maybe slightly unrealistically) happy in the end. Yemelyanychev and his orchestra do a marvelous job with timing and with attention to the singers to intersperse Handelian orchestral music with harpsichord continuos for recitatives. It is a spell-binding success for all involved and a culmination of the project that unwittingly turned Royal Opera House into the explorers of LOVE.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Yulia Savikovskaya.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.