If Wales is known throughout the world it is most likely for its singing. The Welsh have often been heard to refer to it as “The Land of Song,” and although that might conjure up images of the echoing majestic voices of a Male Voice Choir, or Shirley Bassey’s wide arms, Tom Jones’ thrusting hips, or even Harry Secombe’s Sunday evening hymns, the significance of this national attachment to “the voice” goes deeper than a simple love of singing. Wales’ deserved reputation for choric excellence has something much more keenly to do with communities, with social center-points, but also with performance. Perhaps Wales’ preeminent literary figure, Dylan Thomas became a celebrity during his lifetime not merely for his verse (which is often obscure and difficult), but for his presence at the podium on his lecture tours, and for his voice. His poetry readings had an ancient, almost deific, sonorous theatricality to them. Thomas had spent time working in BBC radio, and the recordings of his voice now apparently only give a taste of the power he held over an audience. The Bloomsbury Review referred to its “incantational rhythms, its intoxicating iterations,” and critic R.B. Kershner referred to Thomas as “the Celtic bard with the magical rant, a folk figure with racial access to roots of experience which more civilized Londoners lacked.”

The Celtic Temperament

The best of Wales’ performing arts is always close to the needs of these elements–poetry, presence, and the “incantational” darkness of the Celtic temperament. You can see these in our most famous exports, and they shimmer in the icons of Richard Burton, Hopkins, and Dylan Thomas. There is something deep-seated in the Welsh psyche that tethers “performance” to a sense of national identity, that attaches the rhythms of history, of pre-history, of myth and legend, to the national bloodstream. We have our theatres, our dance studios, but Wales is a stage all of its own, and our modern performing arts is never far from acknowledging this.

Wales’ literature can be dated back to the myth cycle The Mabinogion, Britain’s earliest prose, and this collection of ancient fairy tales continues to inform our literary and theatrical traditions, not just with its stories, but with its ethereal rhythms and peculiar tones. Walking the Welsh countryside, it is easy to feel nothing has changed since the time when The Mabinogi were first performed as part of what we now term “the oral tradition.”

This tradition, of course, in a modern setting, weaves and winds through a complex bilingual history, starting with Welsh, and on through its attempted annihilation by the English, to a relaxation of Parliamentary and educational prejudices toward Welsh in the late twentieth century, to a situation where Welsh is once again taught in schools. Wales today is a country that practices its art in both languages. Arguably the relationship between Welsh and English is now more integrated than it has been in a generation, and the Welsh Language Act of 1993 has meant that the performing arts is a vital part of the efforts to sustain Wales’ traditional native tongue. For a long time, Welsh language and English language art moved in parallel, but now this is less and less the case. English aristocrat Lord Howard De Walden made great efforts, and was partly successful, in the early part of the 20th Century, in championing a Welsh National Theatre. It then took until the early part of the 21st century for the National Theatre dream to come to full fruition. De Walden, who had learned Welsh after inheriting estates in Wales, advocated for a bilingual National Theatre, however by the time it came around, it was conceived as two theatres, one for each language. In the last few years, bilingual productions have begun to sprout up, as well as small independent companies such as Triongl and Criw Brwd. In Wales now the first generation of school kids who have benefitted from Welsh language education are entering maturity, and they are bringing their experiences of life in a bilingual culture to the stage.

The norm, however, is still to have the two languages apart from one another. Wales has two national theatre companies: in Welsh, Theatre Genedlaethol Cymru (founded in 2003), and in English National Theatre Wales (founded in 2009). These two companies are tasked with creating work that speaks of Wales in all of its complex forms. Both of these companies have strong traditions of working embedded into communities, into the Welsh landscape, rejecting the traditional theatrical expectations, rarely mounting shows in conventional spaces. For better or for worse, they push boundaries, often physically. There is an unfounded but popular argument that Wales does not have much of a theatrical tradition, but what those who subscribe to this mean is that the tradition that does exist is not always easy to identify from an Anglo-centric perspective of theatre’s modern development. Wales’ theatrical tradition does not look like England’s, one founded on the solid roots of Shakespeare, and so always in thrall to the trodden boards. For a national company to be tasked with understanding the hazardous cultural and geographical colors of a country like Wales, one in which the tribal confluences meld and flow in uncountable complex ways, an equally fluidic approach to performance has been needed. Wales is a nation small enough (3.2 million people) for innovation to thrive. And sometimes it does.

Of course, it is not so simple as just having a creative petri dish of a country, a national push on radical experimental adventurism, there are still gatekeepers, still overseers, and still the whims of the presiding neo-liberal political agenda to contend with. The performing arts in Wales would be unrecognizable, indeed most likely non-existent, without the support of public funding bodies that are themselves answerable to the Welsh Government.

Money

In 1999, Wales became a devolved nation, winning the right to govern itself and decide many of its own laws, to devise its own strategies for health, education, and environment, amongst other things. But apart from the tectonic shifts in governance and politics, it saw a shift in the way Wales could imagine itself. The establishment of the two national theatre companies in the following years were an iteration of this imagining. Both companies are not simply symbols to the larger world–although they are symbols, of both confidence and ambition–but they are part of the armory of any truly independent nation. Welsh theatre now has solid national institutions in receipt of substantial funding and moral support from government. They are cultural ambassadors, and morally, they represent Wales.

The way that these organizations can exist is down to the fact that both national theatre companies (along with National Dance Company Wales, Welsh National Opera, and Wales Millennium Centre) are members of Arts Council Wales’ Arts Portfolio, which means they receive a core injection of Arts Council money annually. National Theatre Wales receives in the region of £1.5 million a year, Theatr Genedlaethol just under a million. (A full list of who is in receipt of ACW’s £27 million Arts Portfolio pot can be found here). There is, as a result of the system, a huge network of freelance professionals and independent companies in operation who have to go cap-in-hand to ACW on a project-by-project basis. You will see on the Portfolio list many venues in receipt of funding, and this is the final corner of the ecological diagram: Funding bodies–National Companies–independent/freelance–venues.

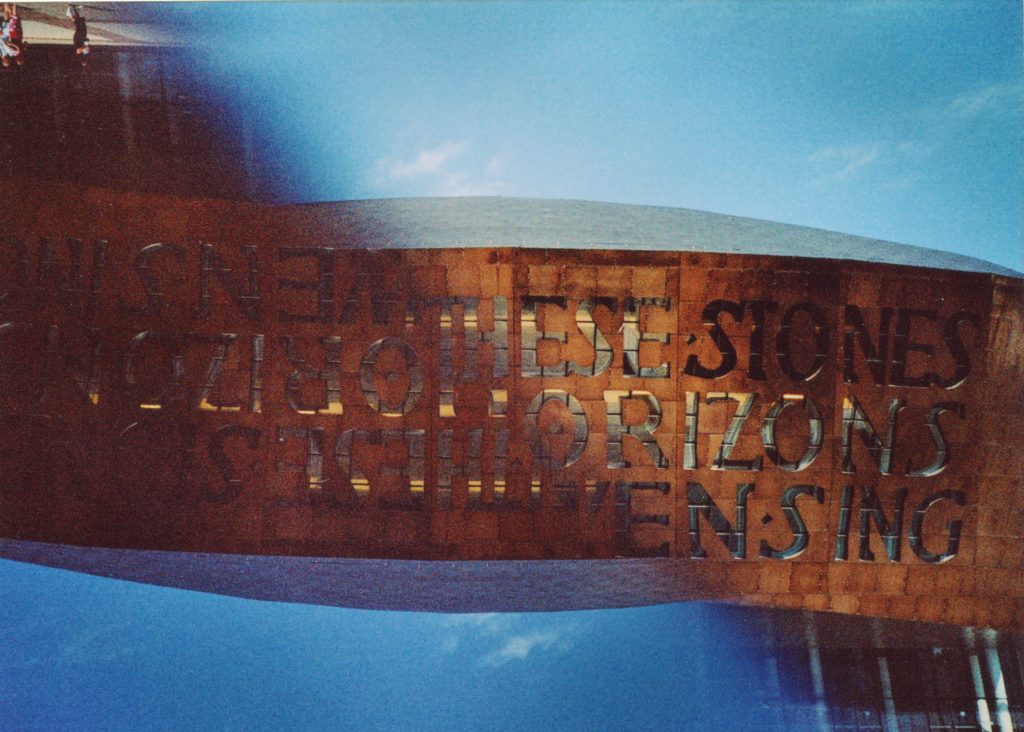

Wales Millennium Centre ©Richard P J Lambert

Politics

What this dependence on public funding means, to render simple a complex subject, is that the performing arts for non-Portfolio organizations have been moving for some time in the direction of box-ticking for Arts Council priorities. This should mean that there is no room for self-indulgent work and that everything funded will have a clear goal of contributing to the greater good. This is art as political outreach, as the Arts Council subscribes to Welsh Government political strategies in order to maintain its slice of the ever-diminishing pie. The definition of that “greater good” is inevitably determined by the political consensus, and here lies the problem: art may very well have the power to democratize, but art itself is rarely the product of democratic thinking. In Wales, art now must contribute to education, to empowerment, to social mobility, or it is not worthy of subsidy from the public purse. This is noble, but also ignores the genius of the unintentional. This central funding ideology means that there is work now not being created in Wales because it does not fit the political criteria of the nation’s governors. This is all very well while those ideologies fit a progressive, quasi-liberal agenda, but in the wake of the Brexit vote, can Wales be sure that such a model cannot be dismantled, or indeed, repurposed?

In recent years, “diversity” has been the buzzword. Arts Council Wales have been very keen to fund work that can show it has diversity at its heart, as it tries to make up for the embarrassing shortfall Wales has in this area. This is a good thing. Also, the preservation and promotion of the Welsh language has been imperative. This is also a good thing. But it does mean that the performing artists in Wales, although having a vital safety net, can sometimes be dancing to somebody else’s tune. The Arts Council passes down the needs of the political agenda of the Welsh Government to the artists, as part of a project to connect the arts to the government definition of national identity. It is not just (or even) that our work must be good, but that it must fit the political strategies of this particular democracy.

But how deep does this strategy of “Welshness” run? Diversity, in all its incarnations, is now something just beginning to work its way up from the floor to the boardroom. Cultural diversity in the performing arts reflects a culturally diverse Wales. But the fact that many performing arts organizations in Wales can boast phenomenally talented women in the top jobs does not hide the fact many of these women have come here from beyond Welsh borders. It is inevitable that at some point in the future, if not already, Wales’ performing arts communities will have to ask themselves whether Wales needs to nurture a mainline to that Celtic temperament that makes Welsh work irrevocably “Welsh,” or whether it is right to allow it to slip away. The replacement is political box-ticking.

This nationality question is not a nationalist one, but rather a question about why Wales does not have the structures in place to develop young Welsh talent into people who can fill these positions? Maybe this will come in time, but why, you may reasonably ask, is the time not now? If the performing arts of Wales have such an umbilical link to the Welsh soil, as I have argued, and if the scene is so creatively healthy, as is evident, then why do we so often recruit from outside Wales for the top jobs?

The Scene

But this central Arts Council support system should never be underestimated. I have traveled to countries all over the world where governments have no inclination to fund arts and culture in the way we do in Wales, and there the most prominent creative voices inevitably are those with the financial means to platform their own work. In Wales, a huge number of performance artists come originally from working-class backgrounds, and those working class values informs much of the work to be seen. Welsh drama is not awash with scenes set in drawing rooms, public schools, or garden parties; it is the drama of the council estate, the drama of the mines, of the village hall.

This working class, Celtic heart, is what gives Wales its inimitable voice. And arguably we are in a golden age of international recognition, seemingly without any compromises to these values. The Sherman Theatre in Cardiff has managed to create a successful brand out of the partnership of artistic director Rachel O’Riordan and playwright Gary Owen. Tamara Harvey is putting out much-lauded work at Theatre Clwyd in Mold. In the last few years, The Other Room, Cardiff’s independent pub theatre, has been a hit with critics and awards judges. Make no mistake, sustaining a company in these uncertain times is no walk in the park, but even so, companies like Torch Theatre in Milford Haven, Theatr Bara Caws in Caernarfon, Volcano Theatre in Swansea, and myriad others, manage to put out interesting, challenging original work under the most difficult of financial conditions.

Despite the usual professional rivalries and the challenging geography of Wales, the performing arts industry is a community. Collaboration is natural, it is oxygen. This stretches out into the communities, as well as out into other branches of theatre. Wales’ most successful circus troupe, No Fit State, is a prime example of the common business model for companies, running workshops and development opportunities with the public as a central part of their Modus Operandi. National Dance Company Wales, similarly, is redefining how the regular person on the street understands contemporary dance. Caroline Finn’s work while there has been some of the most exciting created in the performing arts in any medium in Wales in the last decade, and it has seen NDCW connect with new audiences. And as well as reaching inwards to Welsh communities, Wales’ artists are getting better and better at reaching out.

Wales and the Wider World

Even as the insanity of Brexit looms large, the relationship between Wales’ performing arts companies and Europe has never been stronger. Some of this is down to the hard work of Wales Arts International, the international arm of the Arts Council, headed by Eluned Haf, and the arts team at British Council Wales, headed by Rebecca Gould, (who herself has a formidable CV of artistic jobs stretching back over the last 15 years that includes stints at the Royal Shakespeare Company, Theatre Royal Plymouth, and National Theatre, London). Gould has been a very visible figure in the revivifying of international relationships for Welsh performing artists. British Council Wales and WAI are prime examples of enablers, organizations who release funds and broker relationships so that Wales’ performing artists can create international partnerships, tours, and showcases. Their work has never been more keenly felt.

This has been vital for the non-Portfolio funded companies to spread their wings. Hijinx, for example, is a company that puts on work by disabled practitioners and hit shows such as Meet Fred have toured Europe and further (most recently China) to warm and enthusiastic responses. The performing arts of Wales have for several decades now had an international feel, from the tours of Gododdin in the late 1980s, to an entire festival of Welsh performance work in Dresden, Germany in April of this year, Szene:Wales. That festival, in fact, proved to be the perfect microcosm for what an audience can expect from the output of Welsh theatre. Jo Fong’s cutting-edge, playful experimental dance piece, An Invitation…, sat comfortably next to Dirty Protest’s blistering drug-fuelled one-man show Sugar Baby (which has just enjoyed a second sell out year at the Edinburgh Fringe), and then in turn with traditional storytelling of branches of The Mabinogion from the charismatic Michael Harvey and Adverse Camber, Dreaming The Night Field.

That Celtic heart continues to beat in the performing arts of Wales. It has survived the threats of the past and it will surmount the challenges of the future. The complexities of the Welsh identity, often cited as hurdles, will in truth go on creating a vibrant scene made up of a multitude of paths leading out from the same soil. The performing arts of Wales now not only reach back into the mists of time, but they reach into our schools, into our structures of wellbeing, into our workspaces, our hillsides, our pubs and hospitals, and they tell the stories that make a nation what it is. Such a community needs careful protecting, it needs vision in its leadership, but it is vibrant, innovative, and essential to all of Wales’ ambitions.

Gary Raymond is a novelist, critic, editor, and broadcaster. He is one of the founding editors of Wales Arts Review and has been editor since 2014. He is the author of two novels, The Golden Orphans (Parthian, 2018) and For Those Who Come After (Parthian, 2015). He is a widely published critic and cultural commentator and is the presenter of BBC Radio Wales’ The Review Show.

This article was originally published on IETM’s website on August 28, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Gary Raymond.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.