The House of Bernarda Alba has engendered no shortage of spin-offs — dance and film adaptations like those of Eleo Pomare, Mats Ek and Mario Camus, as well works that pick up the piece’s characters and present them in the aftermath of Adela’s death, as with Migdalia Cruz’s Another Part of the House. Poncia is an addition to this oeuvre, a solo performance that reconfigures Federico García Lorca’s 1936 play, presenting the action through the perspective of the housekeeper that helps run the Alba home.

First seen in 2023, Luis Luque’s piece begins in the aftermath of Adela’s death. Poncia is the sole narrator, confiding in the audience that something is amiss in the Alba household. Adela’s death has been covered up with the cause of death erased. There is a pattern here, as with so many of the events that preceded it. Bernarda wants to pretend nothing is different and nothing has changed but it has: there has been no wedding and Adela has now disappeared for good. The house is in shock, managing the communication around the death. The text deploys Poncia’s dialogue but also has the housekeeper take on the words of Bernarda, her mother María Josefa and Adela. The play is re-presented as reported action through Luque’s adaptation.

Monica Boromello’s set boasts fluid curtains that flutter, conceal and reveal. Dust falls in the opening moments of the play; at times it looks a little like snow. Poncia appears from behind the curtain, a little hesitantly at first as she makes her way towards the growing pile of dust. Lolita Flores has a hoarse, rasping voice. It has something of the androgyny of María Casares, only the tone is different, a little less musical, with a marked Andalusian inflection. There is an intensity to her stare and stillness. This is a woman unafraid of holding her ground. She appropriates Bernarda’s opening and closing words – silencio (silence); a means of imposing her own presence on a world where Lorca gave her a secondary role. Flores isn’t afraid to deploy silence in the production, playing with the same tension between what is said and unsaid that is such a feature of Lorca’s final play.

That said, past Poncias in productions of Lorca’s play, have often had a huge impact on its reception: from Julieta Serrano’s wily servant in Calixto Bieito’s 1998 staging to Rosa Maria Sardà’s witty presence in Lluís Pasqual’s 2009 production. Here Poncia delivers the story straight to the audience as if we are all additional members of the household. “Lo hecho, hecho esta” (What’s done is done) she states pragmatically; she sees it as her responsibility to protect the house and its reputation.

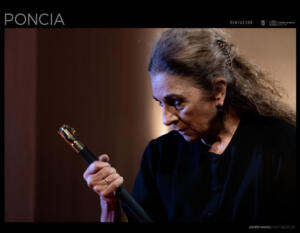

Dust, prayers and mourning for Poncia in the aftermath of Adela’s suicide. Photo: Javier Naval

Flores’s Poncia is dressed in black, in mourning. Her hair is tied back. Barefoot, she circles around the pile of dust piled up at the front of the stage. She pulls back the curtains, each like a layer of the past that is pushed away. She advices Bernarda to open her eyes, she confides in her, lowering her voice, but Lorca’s matriarch — haunting the stage like a ghost — doesn’t appear to be listening. At one point Poncia gathers the curtains like sheets, as if they are a trousseau for one of the sisters, also evoked by Poncia through words rather than a physical presence.

Poncia evoking each surviving daughter in turn through the pouring of a glass of milk. Photo: Javier Naval

She pours four glasses of milk — one for each of the four remaining daughters. She addresses each glass in turn; each sister made visible for the audience through the description that Poncia provides. She accuses Martirio of being responsible for Adela’s death by lying about Pepe el Romano. Poncia demonstrates great compassion for Adela – she is grieving her death. “Ha muerto una hembra valiente” (A brave female has died) she reflects sadly.

Poncia speaks to Bernarda through the walking stick. Photo: Javier Naval

In the next scene, she brings on Bernarda’s walking stick; her personification of Bernarda has an element of contempt: “los pobres son como animales; parece como si estuvieran hechos de otras sustancias” (the poor are like animals; it is as if they are made of other stuff), she states, appropriating Bernarda’s line to neighbours in the opening act to here throw it back in the matriarch’s face. There is tenderness for Adela but bitterness for Bernarda. She may not directly accuse Bernarda, but her tone makes it clear that she holds Bernarda in part responsible for the youngest daughter’s death.

There are also moments of tenderness and humour in Poncia’s recollection of her marriage to Evaristo. She sits and confides in the audience, as if they were Bernarda’s daughters, sharing tales of her courtship and the routine of married life. Paco Ariza’s lighting provides pockets of action on the stage. It is as if Poncia finds corners of the house of Bernarda Alba where she can talk to the audience without the mother’s surveillance. In the programme to the production, the director describes Poncia as being trapped in a prison of sheets in a house trapped in silence. She is the witness to what has happened, to the comings and goings in the house, to the death of Adela and its consequences.

Lolita Flores holds the stage convincingly for the piece’s 70-minute duration — at times complicitous, at times more reticent in her conversations with the audience. There is a no-nonsense approach to her advice and frustrations. She tells the story it as it is; reappropriating the narrative from the perspective of a character who is often left up to mop up the mess left behind by her mistress. She removes a shirt in the final third — it is as if she is removing layers to venture closer to the truth: less curtains, less masking, just the story as she sees it.

To a fine lineage of Poncias can now be added Lolita Flores; her mother, Lola, may have wanted to take on the role in productions by Miguel Narros and José Carlos Plaza that never materialised, but it is Flores who makes Poncia her own in Luque’s elegant staging.

Poncia, produced by Pentación Espectáculos and the Teatro Español, plays at the Teatro Bellas Artes Madrid from 26 November 2025 to 15 February 2026.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.