Khaled Hosseini’s 2003 novel The Kite Runner is a vividly descriptive and often gripping tale of guilt and expiation, class conflict, and wrenching refugee experience, set mostly in Afghanistan before and during the first Taliban rule. The book was enormously popular in the U.S. when it first appeared, providing a sumptuously detailed picture of life in a distant and confusing land that America had just become more involved in than it ever anticipated and was eager to better understand. The American affection for the book was, I believe, partly due to its juxtaposition of horrific descriptions of Taliban brutality with the immigrant-hero’s successful American assimilation, which tapped into America’s deep desire to see itself as a savior just as it was becoming a blundering occupier. (We had just invaded Iraq.)

Film and stage adaptations of The Kite Runner, written and produced separately, quickly followed the novel, coincidentally both appearing in 2007. The film, directed by Marc Forster and written by David Benioff, was an indie hit, featuring breathtaking shots of soaring kites and rugged scenes (shot in dusty and bustling locations in western China) that beautifully evoked the lost milieu of vibrant and colorful, pre-Taliban Afghanistan. A luxuriant sense of place is a signal distinction of the book.

Matthew Spangler’s stage adaptation, alas, has no such atmospheric potency and few substitutes for it, which may explain why it never came to New York before. It is a wordy, plodding, and claustrophobic play first staged at San Jose State University, where Spangler teaches, and then produced professionally at San Jose Repertory Theatre in 2009. Giles Croft directed it at Nottingham Playhouse in the U.K. in 2014, and that production moved to the West End in 2016-17 and has now opened on Broadway. The show has some strengths — one marvelous lead actor, for instance, and a lovely musical underscore by the tabla-player Salar Nader — but any fan of the book or film, watching this play will likely miss the in-depth view into Afghani culture they both made palpable.

Hosseini’s title refers to a traditional winter game (later forbidden by the Taliban) in which boys fly kites with ground-glass-coated strings and compete to cut one another’s lines. “Running” (or chasing down) the severed kites is part of the fun, and the narrator Amir’s childhood friend Hassan is considered a masterful “runner.” Amir is a wealthy Pashtun (the privileged majoritarian class) whereas Hassan, illiterate and unfailingly loyal, is a Hazara (an oppressed and disdained minority) and a family servant along with his father. Amir’s father, the tough and manly Baba, complains of Amir’s softness (“there’s something missing in that boy. You know what happens when other boys tease him? Hassan steps in and fends them off.”) The story turns on Amir’s cowardly failure to defend Hassan when, trapped by Pashtun bullies while running a kite, he is raped in an alley.

The guilt-stricken Amir contrives to blame Hassan for a theft to get rid of him and he and his dad move away, leaving Baba inexplicably disconsolate. The rest of the very dense and twisty plot involves Amir and Baba’s perilous flight from Afghanistan after the Soviet invasion, their resettlement in the San Francisco area, Amir’s marriage and early success as a fiction-writer and a late revelation about Hassan’s paternity that you can probably guess. The Americanized adult Amir is forced to face his demons by sneaking into Taliban-controlled Kabul to rescue Hassan’s orphaned son Sohrab.

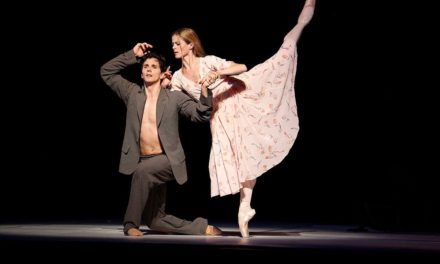

Spangler and Croft do find some effective, albeit bleak, ways to theatricalize all this. Amir and Hassan are played by adult actors — Amir Arison and Eric Sirakian — whose portrayals of slouchy, rubber-limbed boys are amusing and endearing. Sirakian in particular is so sweetly guileless as both Hassan and Sohrab that he steals several scenes. The set (designed by Barney George) is also neatly malleable, using an array of projections (by William Simpson) against a row of irregularly shaped posts and kite-shaped draperies to evoke far-flung locations from Kabul to Peshawar to San Francisco.

None of this, however, can overcome that (1) the play’s physical business is consistently disappointing — lame kite-flying with little props on wires, innocuous violence by villains neither menacing nor convincing in fights; and (2) the play leans too heavily on narration, burdening Arison with storytelling at the cost of his character-acting. Spangler clearly felt obliged to fit in as much of Hosseini’s vast plot as he could, when thinning it might have made for a stronger drama. The play lasts two and a half hours, yet still rushes through many events and transitions so abruptly it reduces them to cliches: a jubilant arrival in San Francisco conveyed by brief grooving to Kool and the Gang’s “Celebration,” for instance, or Baba suddenly clutching Amir’s childhood notebook as a totem as he’s wheeled off to die of cancer.

One innovation the show introduces I did appreciate: its modernized portrayal of Soraya, Amir’s wife. Soraya is a woman with a past. The daughter of a hard-nosed, exiled Afghan general, she once ran away with an Afghan man and lived with him for a month. The general extracted her by threatening to kill the man and himself, then moved the family from Virginia to the East Bay to escape the scandal. In both the book and the film, Soraya is chastened by this experience and becomes compliant with her dad’s strict honor code and docile in the face of his tyrannical oversight.

In the play, by contrast, Azita Ghanizada plays a thoroughly Americanized Soraya who is confidently independent, assertive and unafraid of her dad. With numerous eloquent tsks and eye-rolls she makes clear that compliance is a charade she plays to get what she wants, and she disagrees with Amir as well as the general at times. Once, when Amir tells the general off for disrespecting Sohrab, she grabs her husband and kisses him like a movie star.

This adjustment is refreshing. It makes Soraya’s character more substantial and also enriches the story’s warily optimistic ending in which Amir becomes the subservient kite-runner for Sohrab and finally recognizes how much pain and damage he caused by blindly accepting his Pashtun class privilege. That recognition, we know, was enabled by his immigrant experience, which made him a climbing member of an underclass (Baba had to work in a gas station) and a beneficiary of America’s professed class-leveling. In the play, his wife seems to complete his social education.

It’s worth recalling, in this vein, that The Kite Runner film was banned in Afghanistan by the American-installed government of Hamid Karzai, both because of the rape scene and the depiction of Pashtun arrogance and brutality. In fact, several of its Afghan child-actors had to flee Kabul for their safety. Hosseini’s story, in other words, was never safe or triumphal for most people inside his native country, only for those “privileged” with emigration or exile. Now, of course, the Taliban is back in power and the film controversy may seem like ancient history to some. Not to me. With America threatened by its own revanchist movement to strip women of their rights and personhood, I don’t regard anything as reliably ancient, and I value The Kite Runner, in all its iterations, as a sobering reminder of everything now teetering in the balance.

adapted by Matthew Spangler from the novel by Khaled Hossseini

directed by Giles Croft

Helen Hayes Theater

This article was originally published by TheaterMatters on Jul 26, 2022, and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jonathan Kalb.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.