How her truth split critics and why she doesn’t really care

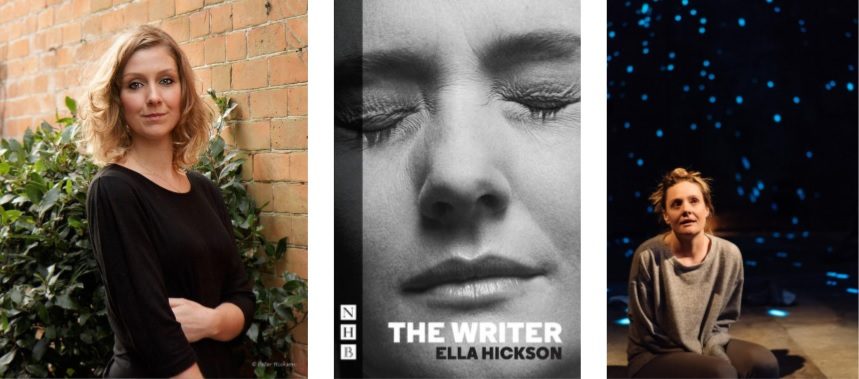

Ella Hickson stopped worrying about the critics, and wrote one of her most fulfilling works to date. Ella Hickson is a powerhouse playwright. She’s done everything: adaptations, love stories, the list goes on and on. But, her latest work, The Writer, which premiered at The Almeida Theatre in London this past spring, is not what she, nor anyone else expected. The Writer is a play about a female playwright who is struggling to find her voice in an industry primarily dominated by men. Hickson opened up about her vulnerability whilst writing this piece, and just how easy it was for her to tap into that space.

Riley Rudy (RR): The first scene of your play, The Writer, is between a man and woman. The woman is criticizing the play to this man, who happens to be the director of the show. She holds nothing back in describing her problems with the play she has just seen, specifically noting the inherent sexist qualities. This scene completely struck me as I had never seen anything like it on stage. Was this something you have been wanting to write for a long time?

Ella Hickson (EH): I think it was the only experience I’ve had in a long time where I was writing something for myself and not writing it for the sake of commission or getting a job done. It’s quite a selfish play in that sense.

RR: Since you were writing from such a raw, vulnerable place, were you ever afraid people would label you, for lack of a better word, as an angry, raging feminist?

EH: I wasn’t worried about the feminism so much. I was more worried about the self-indulgence. Like all I did was sit and write exactly what I wanted to write and I think that shows a lack of responsibility. I wasn’t really thinking about anybody else at all. My only principle for it was being relentlessly honest, and I think I was doing that because I was in a very protective place. I was on a retreat in America, so I felt like that was safe. I was doing that honestly in an environment where it felt like that honesty wasn’t going to have any consequences. It was just a story. But, of course, you write that story, and you bring it back to London and it does have consequences and it is the real thing. It’s not as straightforward.

RR: Did you feel like, because you were in such a safe space and you felt like you could be so honest, that you didn’t hold anything back or was there something you held back?

EH: No. There were a few extra bits that I didn’t include, but that was just because they weren’t on the theme. It was just a different way of writing. There was no censorship. There were no critics. There was no nothing. Writing exactly what you wanted to write.

RR: Do you feel like in the other plays you’ve written that you were writing with the critics in mind and that this was the first time you let go of that?

EH: Yeah it was the first time I let go. A lot of the time I’m thinking about structure or whether the story will work. There are lots of constraints on you normally, and those constraints mean that you can’t just sit and write what you want to write. Because usually, you have to write in a certain way. It’s quite rare that you have a situation where the only conditions on writing are your own preference. You usually have to consider other things. Or I find myself taking jobs where I have to consider other things. You don’t usually have that self-indulgence, and I don’t mean self-indulgence in a bad way, I just mean where the only conditions are getting to write what I want.

RR: Do you think this honesty that you found while writing this play will transfer or stay with you when writing future plays or was this just a special moment in time where you felt that freedom?

EH: I certainly feel like I have to go back into my bit for a little while because it was also the material. I may have to wait for a play to be like that in me in order to get it written. But, I don’t know the answer to that. I feel like I will do it again, but not for a little while and probably not from such a personal perspective. There are other things I want to write about, but they aren’t my experience, so it’s different.

RR: There are a lot of lines that have stuck with me and struck me in this play. One of the lines you wrote you said, “I want the world to change shape.” How do you want the world to change shape and do you think that theatre can change the world?

EH: When I wrote that it came from a really clear place and a really clear demand, but I don’t know if I feel that anymore.

RR: What do you think changed for you?

EH: I don’t really know what that line means in the real world. That came from a real sense of emotion of what I wanted the world to feel like and it was collaborative and it was female and it was calm. But theatres in London still have to make money. The audience isn’t going to put up with bra burning pieces all the time. I get it. I get the purity of that impulse. And it’s incredibly inspiring. And it was incredible to write from that pure shout of rage. But, that’s not always art. That’s not always the responsibility of art. That pure shout of rage creates a lot of feeling in people, but then they don’t know what to do with that feeling. It’s hard. It’s not clear. You just have to trust that it’s doing something, that it is waking people up, that it makes you feel a thing. And that that energy has applications somewhere. I would love the world to change shape, and I would love to see a kind of freedom that was in that play to exist more constantly in more of my life. But, I just don’t know how or what that is.

RR: Since, like you said, there can’t always be a bra burning type play going up, were you expecting critics to split and have differing opinions? After you wrote it and after you put it out there, were you hesitant since it came out of a place of complete honesty?

EH: I just wrote down what I felt to be true. I didn’t engage my inner critic at all. I didn’t ask myself any questions and I didn’t have any doubt for the first time ever. I wanted to write a thing that was completely without second-guessing and thinking about it. I wanted to write it from a place of instinct. So, when people aren’t liking it, they aren’t liking what is instinctively you. I didn’t ask myself any questions about it, so when other people like it or don’t like it…Do you know what I mean? Like when you go into a shop, and you’re looking for a dress to wear to a wedding and you’re like it can’t be too long and it can’t be too short and you go through that whole thing and then somebody says that they like it then it’s like they’re honoring that decision making process. But, if you go to a shop and you see a pair of gold sneakers and you just buy them you aren’t like do I like them? You just say who cares I just got them. Other people’s opinions, in that case, don’t matter because you haven’t made up your mind either.

RR: If you don’t find validation or success from critics, is it then coming from yourself?

EH: With that play in particular, yeah. With that play, I wrote exactly what I wanted to write, and the moment that I finished writing it, I didn’t care what anybody thought. It was a real abdication of responsibility. I took responsibility for nothing. Not the outcome, and not the implications.

RR: Had you done that with any of your other plays before?

EH: No. Never. I was always thinking about the audience, thinking about the producers, whether it’s good or not. That level of freedom and carefreeness…I don’t know the answer. I feel like I’m betraying myself if I’m ever working from a place that isn’t that. Maybe I’ve proved to myself that incredibly honest and freeing is the place that makes the best work. My job is to keep being honest. But, the months before this play was going up, were incredibly vulnerable and anxious in a way that other plays really hadn’t been. I felt weirdly skinless for quite a long time.

RR: As a young female artist and performer, I feel a responsibility and pressure being a woman like what roles I would take and what roles I wouldn’t. Do you feel that pressure as a female playwright to write more female characters? Do you feel any sort of that responsibility as someone who has such a powerful voice in the theatre community?

EH: Yeah, I think to a certain extent you have to remember that a lot of that is going to come for free. Like if your politics are in a particular place, and you believe certain things, when you sit down to write a play or you decide what job you’re going to take, you will naturally be drawn to things that are reflective of your way of being in the world. It would be very hard for me to write something that isn’t reflective of my way of being in the world. So, that position and that way of being is going to do a lot of that work for you. Your instincts are going to be shaped by how you feel about feminism and everything else. Your body will just do it for you.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Riley Rudy.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.