Rome, 9th February 2020.

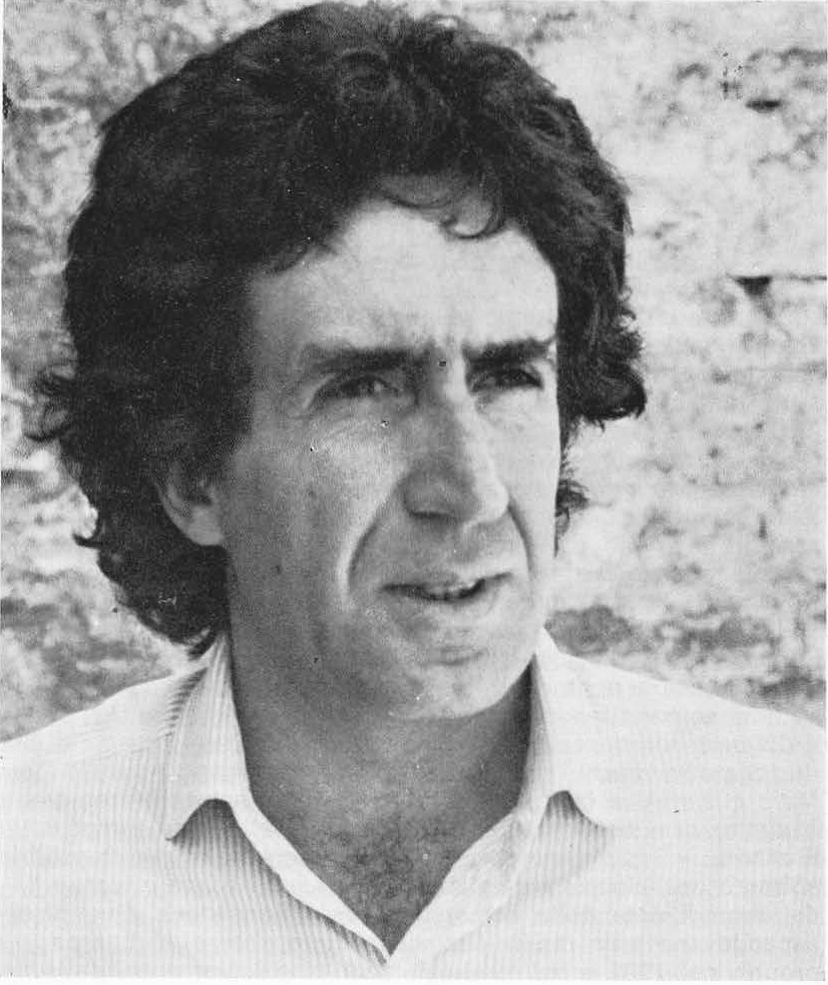

“Can I get some paper? Some cream-colored paper? And a pen?” It is an autumn evening of 1982 in Trieste; the company performing Stanisław Przybyszewska’s L’affare Danton (The Danton Case) at the Teatro Stabile are sitting down to a dinner of fresh fish from the sea just outside. Giovanni Pampiglione, director, actor and translator, has invited Andrzej Wajda over to direct his Italian translation, knowing the play was important to Wajda: only a year ago it had been in Gdańsk, poignantly opening immediately following the shipyard strikes (for better working conditions and freedom from the Communist Party, evolving into a single national trade union, ‘Solidarity’). A few months later, Wajda’s film version starring Gérard Depardieu, would be heavily criticised by the French Left-wing press who thought it an offensive portrayal of Robespierre and the Revolution, while the Polish continued to think it a metaphor for their current situation under martial law. But here in Trieste, in the atmosphere of the evening, political tensions are temporarily forgotten. Wajda sits at the table peacefully sketching on the cream-paper and, only at the end of the evening, shows it to his friend. Pampiglione is touched, “You’ve made me look like Byron,” he says. In his 2016 Italian-Polish memoir Terminus Nord, Pampiglione uses the portrait as frontispiece.

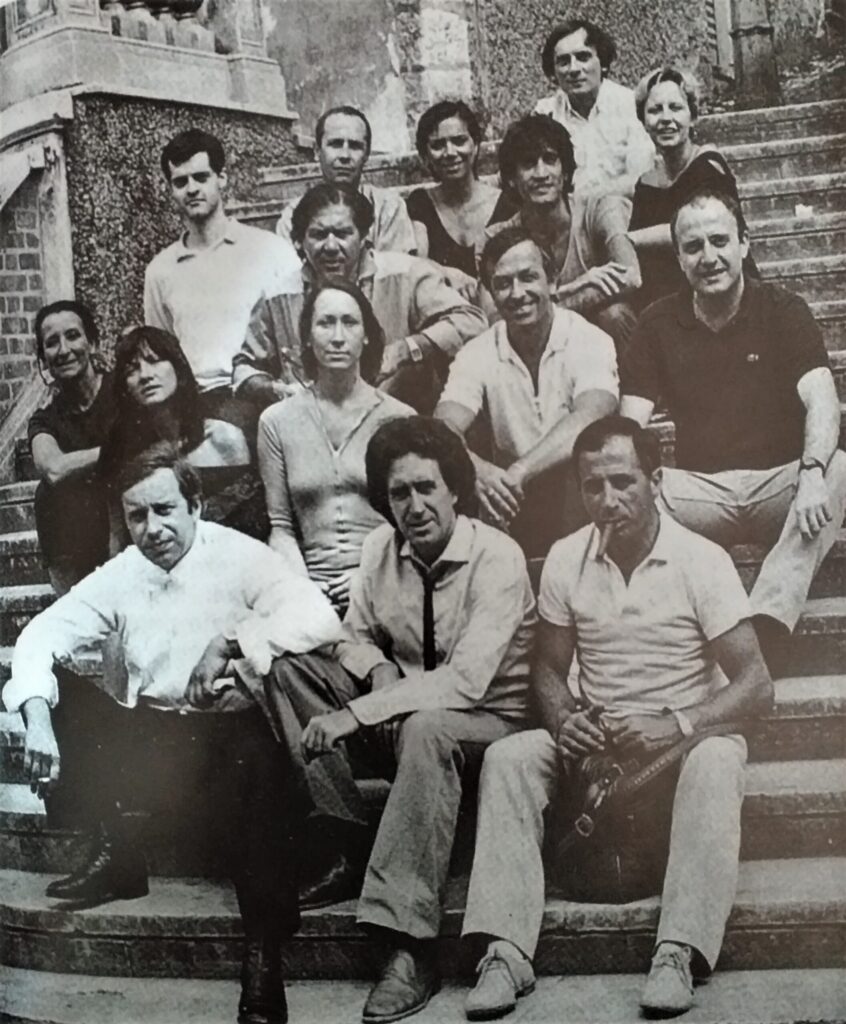

Atelier di Formia, Spoleto, July 1984

(Pampiglione centre, bottom row)

I’m meeting Giovanni Pampiglione in his Rome apartment five months after first meeting in Słupsk during the quinquennial Witkacy conference (S.I. Witkiewicz’s pseudonym). We were in the underground restaurant of Museum of Central Pomerania and he brought me to his table with Janusz Degler, Stefan Okołowicz and Lech Sokoł who have worked together and on Witkacy, his theatre, biography, photography and painting, for over forty years. Pampiglione now asks what brought me to Słupsk from England, and I tell him how I read Daniel Gerould’s translation of ‘Seven Plays’ by Witkacy as a young child, fascinated by the foreign-looking name, and have been haunted by it since.

When I ask Pampiglione what first drew him to Witkacy, he tells me the most important thing in Witkacy is his great imagination; the pleasure of his imagination, his love of dandies, for la bohème. “We didn’t have that in Italy.” There was a sense of restriction in Italy, the heavy weight of Futurism and of Fascism, but this was freedom. “Here there was fantasy.”

Witkacy’s love of dandies. I’m reminded of Witkacy’s self-portraits, of enlarged eyes, reddened lips, elegant costumes, of his Self-portrait as a Woman. And an essay by Dorota Niedziałkowska, which discusses these portraits as manifestations of the dandy figure, relating Witkacy to the ‘emblematic’ figures of Byron, Baudelaire and Wilde. Byron. There is a powerful, seductive air in Witkacy, and I cannot help feeling his presence in the room via the portrait hanging on the opposite wall. It is the portrait of Princess of Astrakhan (1925), in shades of green and blue, facing away from the windows; It is sensitive, and cannot be allowed to fade. The eyes are like black mirrors, always looking. As a young man studying in Warsaw, Pampiglione did not eat for two months so that he could buy it.

So it was this liberating imagination you tried to bring over to Italy? “No, I think he put it in me. I just went with him, he was the leader, I was the young pet.”

And when you were translating him, was it ever frustrating? Was he difficult? I’ve only read him in translation. “No, not really. No. Perhaps when I first began, but I had a special feeling for him. My language grew through Witkacy’s. I spoke in Polish like Witkacy characters.” He hands me his copy of La Piovra (The Cuttlefish) from 1979, his first translation, filled with annotations. Far from being frustrated, Pampiglione loved it; He loved the pleasure of Witkacy’s company. The excitement stemmed from translating everything, not just the words spoken by characters, but the characters’ names too. It was exciting to re-invent these names in Italian, because the names mean more than a character’s designation; they play games with words and sounds, with idioms, with cultural and historical reference. Pampiglione enjoyed the mission of doing his best to translate these references, idioms and ironies that could have no direct equivalent in his native language.

There was never an aspect you got angry with? “No. It was a story of friendship. I was so close, so fond of him, that maybe I was Witkacy.” I wonder if that was the mysterious shadow Wajda managed to capture when he gave Pampiglione an air of Byron in his portrait, the figure of dandyism Witkacy embraced. He says he owes his life in theatre to him. “Without him, I don’t know how I would have ended up. He gave me life.”

The logo of the Atelier di Formia

In 1982, staging his translation La Piovra in the 25th Festival of Two Worlds, Spoleto, Pampiglione wrote on the programme that it is also to Witkacy that his international theatre company, in a certain sense, owes its existence.[*]This company was established two years earlier with the name ‘Atelier di Formia’, when Pampiglione invited a group of friends from Poland to work with Italian actors. Formia, the city between Rome and Naples, was the location of its foundation. “A beautiful place,” he tells me, also the place he was married to the actress Carla Cassola. There was a lack of theatrical activity there at the time, and the possibilities for funding were scarce, but with the help of Gennaro Aceto, Anna Mazzella, and Girolamo De Magistris and Guiseppe Marciano from Comune di Formia, the local community financed the project. The choice of ‘Atelier’ comes from a great theatre in Paris, a word with connotations of making and creating.

The particular debt to Witkacy originates from a series of events in Tuscany in February 1980. Titled Witkiewicz Senza Compromesso (Witkiewicz Without Compromise), this grew from a chance meeting on a Rome-Naples train with Carla Pollastrelli, who was working in the Centre for Experimentation and Theatrical Research in Pontedera (from 1985 she collaborated with Jerzy Grotowski, continuing to promote and safeguard his work thereafter). The preceding year Pampiglione had already been working to create an international theatre centre, believing the time had come in Italy to develop Grotowski and Peter Brook’s idea to work with actors and artists from different nationalities and seek a new language of theatre. In this Tuscan Witkacy ‘project’, Pampiglione was able to play out some of his ideas through the production of Loro (They) in Livorno. That was the great rehearsal for Atelier. After this, he realised how exciting it was to speak texts by Witkacy, Mrożek and Jasieński in Italian with an international group. He found it extraordinary that the leading actor, Jerzy Stuhr, could perform so brilliantly in a language he had never spoken. “That was the great gift.” (This same play, directed in English by Pampiglione in London, 2001, prompted a striking response from the actors: Thank you for giving us one of our own.)

About Loro in Livorno, I remember an image from a book by Anna Micińska: a crowd of smiling people holding bottles of wine with ‘Witkacy’ labels on. Whose idea was that? “That was mine,” he replies, he had an ex-architect friend who produced wine, so he organised two-hundred bottles of specially-labelled Chianti to follow the premiere, producing a structure with a white sheet draped over them as a monument for Witkacy. “It was a very Polish idea, I think, there was something of the Cabaret about it.”

This play proved the possibilities of cross-linguistic and cross-cultural understanding. It was not only Italian and Polish actors performing in Italian in Italy (Pisa, Pontedera, Rome, Modena, Milan), but they toured the same performance in Poland. Between May and June 1980, they played in Wrocław as part of the Festival of Polish Contemporary Arts, in Warsaw’s Teatr Ateneum, and in Krakow’s Stary Teatr. According to Pampiglione, it was watched by an attentive audience delighted to celebrate their favourite playwright in its Italian version. It was creating a special and different atmosphere.

And so on 23rd July 1980, the Atelier di Formia was born, performing Mrożek’s Il Macello (The Slaughterhouse) in Minturno’s Teatro Romano. In the inaugural text, the company’s founder and director spoke of his belief in a “timeless temptation to unite and mix languages, experiences, traditions, forms, in order to arrive at a great cosmogony where all individuals, all people, share life and work, cancelling differences, borders and one’s own fear”. Stuhr wrote of his sensation after this first production, that he felt “the victory of an actor who has proved to himself, and to others, that his art which relies on words can be universal”.[†]

Having returned from Poland only a few years earlier, I ask Pampiglione: did the Atelier enable you to have a piece of Poland now that you had returned to Italy then? “Yes.” After the first production, the Polish actors had been so good, he had to keep them; there was no point having actors he did not know from other countries just for the sake of it. No, he told himself, “keep your Poland, come on.”

How about for the actors? Did it give them a freedom they couldn’t have in Poland at the time? “Yes, at the time. Afterwards no, but then the Atelier was over.” During the five years the Atelier was active, it gave the Polish actors Pampiglione had invited the liberty of coming out, spending a couple of months away, and doing work for their country, since this was almost all Polish literature. They had good contracts too. In the inaugural text, Pampiglione wrote of “man’s dream being to travel, to get up in flight, explore, open the doors of his subconscious and go to wonderland”. There are some who “unable to travel, fly in a single step, reinventing everything right beside them, travelling, as De Maistre said, within their room”. It is precisely this the Atelier sought, “to recreate the proximity of a journey through a room, whose doors, though, remain open to offer the possibility to roam and uncover a wider, freer, disturbing, more mysterious horizon”.

Over the course of its first year, borders became increasingly conspicuous. Pampiglione recounts in Terminus Nordhow, by pure chance, he had returned to Rome in the last plane that left Poland on 12th December 1981, before the early morning announcement of martial law on 13th by General Wojciech Jaruzelski. He was directing his and Joanna Walter’s Polish translation of Carlo Goldoni’s Il Bugiardo (The Liar). The first performance took place on the evening of 11th December in the Stary Teatr, Krakow, in an atmosphere fraught with feeling. Never to see this play again, Pampiglione writes the fading notes of his Atelier’s composer Stanisław Radwan remained to signal the “approach of a disturbing and desperate sunset”.[‡]

It must have been difficult to bring them over? “Yes.” In 1982 Pampiglione found he could not get a visa to go to Poland to get seven contracts signed. “I knew the ambassador, the Polish ambassador in Rome Emil Wojtaszek, a nice gentleman,” he tells me. So one day, he went to the embassy and gave him an earnest and elaborate story, telling him that Spoleto, inviting his company to perform in the Festival of Two Worlds, must have an answer now, in three days. He acts out for me how he went with some form of medal on him and declared that if he could not get the contracts signed, he would have to make a public announcement that he was giving up the award and could not perform in the festival. At the time, the press opportunities of this international festival were prestigious, and the ambassador believed such an announcement would be a scandal. “He looked at me and said, give me two days.” The ambassador called Warsaw and told them about the festival and what it might mean for Poland to be under the scrutiny of so many nations. Though it should have taken months for such permissions, two days later, he had the contracts signed.

La Piovra is not only the first drama Pampiglione translated, but he tells me that for him it is also the most important of Witkacy’s plays. I ask him how the audience responded to it in Spoleto in 1982. It was a great success; such a resounding success that instead of performing the ten contracted performances, they were asked to do seventeen. “I saw all my Polish actors coming towards me smiling. Why are you smiling?” They had not received this kind of response during this miserable time for them in Poland. “Because we have another seven performances.” They felt wanted. The theatre was small, Teatrino delle Sei near the Duomo in the historical centre, it had a capacity of about two hundred people. But it was full for every performance. “People couldn’t get in; they were banging on the door as the play started.”

As anticipated by the Polish ambassador, there were radiant reviews from key theatre critics. Pampiglione shows me fragments: “It is a staging in which the poetic, expressionistic folly of the best Polish avant-garde theatre is felt” (Roberto De Monticelli, Il Corriere della Sera, Milan, 9th July 1982); here, “for once, we are faced with a concrete and vivid example of European theatre” (Renzo Tian, Il Messaggero, Rome, 9th July 1982). Guido Davico Bonino in Turin’s La Stampa stated Pampiglione had directed the text “in a disconcerting ‘naturalness’ key, as a dream more true than reality […] he made the characters emerge from the darkness of the cellar as though they were familiar ghosts, and he focused everything on the actors.” This focus rested on the individual actors as they formed the international group, united by Italian translation, facing an international audience: “for a few weeks, our experiences, our languages, traditions and cultures will get confused”, Pampiglione wrote in the play’s programme notes. Appearing a manifestation of the Festival’s titular aim to be ‘of two worlds’, he tells me Gian Carlo Menotti (the festival founder) loved them. They were the first in the festival’s theatre section to be international like this. In Rome’s La Repubblica, Tommaso Chiaretti declared the Atelier “the closest to the desire for novelty and discovery that the Festival should keep essential.”

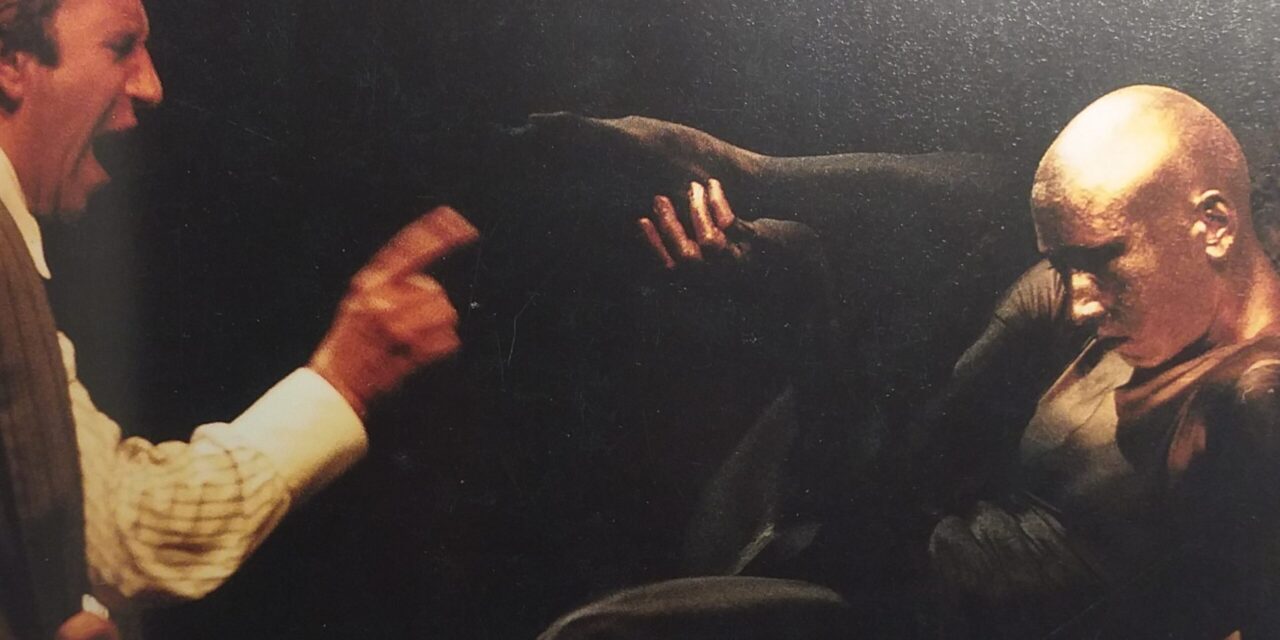

Giovanni Pampiglione, 1982

Pampiglione says his Polish actors were proud to be bringing their culture abroad. The non-Polish members of the company were equally excited to interact with a translation between and across cultures. A few people in Spoleto wondered how it was the company got along so well. One asked Menotti if the team were professionals, because the actors seemed so relaxed, always driving off to a restaurant to sing and play the piano in their various languages. Stuhr, who won the Italian critics award for Best Foreign Actor in 1982 after Spoleto, claimed to owe the Atelier his entrance into Europe’s theatre and art: “the greatest gift Giovanni offered to the Polish artists he invited to Formia was the repertoire he decided to present to the Italian public. His unusually courageous repertoire choices made me feel ‘Polish Theatre Ambassador’ in Italy and Europe.” Pampiglione tells me an especially memorable moment was during the 1984 Spoleto Festival when the fashion designer Gianni Versace had flown in especially to see the Atelier’s performance, and asked Pampiglione how he might get a copy of this excellent foreign play. This was the last performance, as the company closed in 1984 due to changing political situations in Italy.

Its costume and set designer Jan Polewka’s subsequent comment, that the Atelier lives “in spite of everything, and even if only in our hearts!” could not help but remind me of the ending of Stanisław Wyspiański’s The Wedding (made into a film by Wajda in 1972), that Poland lives in the hearts of the Polish people. This connection seemed to tie the Atelier’s work with the work of upholding a sense of cultural identity.

Giovanni Pampiglione is writing his memoirs to be finished later this year. He shows me a painting Rafał Olbiński made for him, an odd-looking grey cloud with dots of red and green floating above a river and distinct horizon containing the Stalinist Palace of Culture and Science. Looking closer, the cloud is not a cloud, but a heart with delicate roses growing from it. Olbiński called it Heart on Warsaw. Pampiglione tells me he does not belong to his country of birth, perhaps half, perhaps a little less. The other half belongs to Poland. “Poland gave me freedom, and I have tried to give her back what I could.” I ask him about the medal on his table with Poland’s eagle and a ribbon of Italian colours. It was a surprise at an event in his honour at the Warsaw National Opera, titled with a line from the Polish national anthem “Z ziemi włoskiej do Polski” (“From the Italian land to Poland”). He was touched as his actors appeared on stage, and the Minister of Culture gave him, the first Italian, the Gold Medal for Merit to Culture, Gloria Artis, for his fifty years of work for Poland.

He takes me in the lift down the Mussolini-era block of flats. His apartment had been his mother’s, and the furniture belonged to his grandmother. He tells me how at the age of ninety-four his grandmother had travelled in the car from Terni to Spoleto to see that last Atelier production, Jasieński’s Il Ballo dei Manichini (The Mannequins’ Ball), coming up to her grandson afterwards saying, “But what a marvellous thing you have done, my dear!” He puts me on the 280 bus, concerned the driver will leave without me: “maybe I see you in Spoleto.”

As this afternoon in Pampiglione’s apartment was not recorded, I hurriedly write a list of everything I remember, beginning: stringless violin leaning against 1984 Spoleto Festival poster. Witkacy work between windows. “My language grew through Witkacy’s. Poland gave me freedom, and I have tried to give her back what I could.”

[*] La Piovra’s Spoleto programme, 1982, available from Janusz Degler’s online archives: https://witkacologia.eu/.

[†] Inaugural text, reviews, Atelier image, Stuhr and Polewka, taken from a publication Pampiglione gave me commemorating the Atelier, with Grafiche Ponticelli, Castrocielo, July 2005.

[‡] Terminus Nord, Instytut Teatralny, Warsaw, 2016, p. 49.

Quotes from these three texts translated by myself.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Gertrude Gibbons.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.