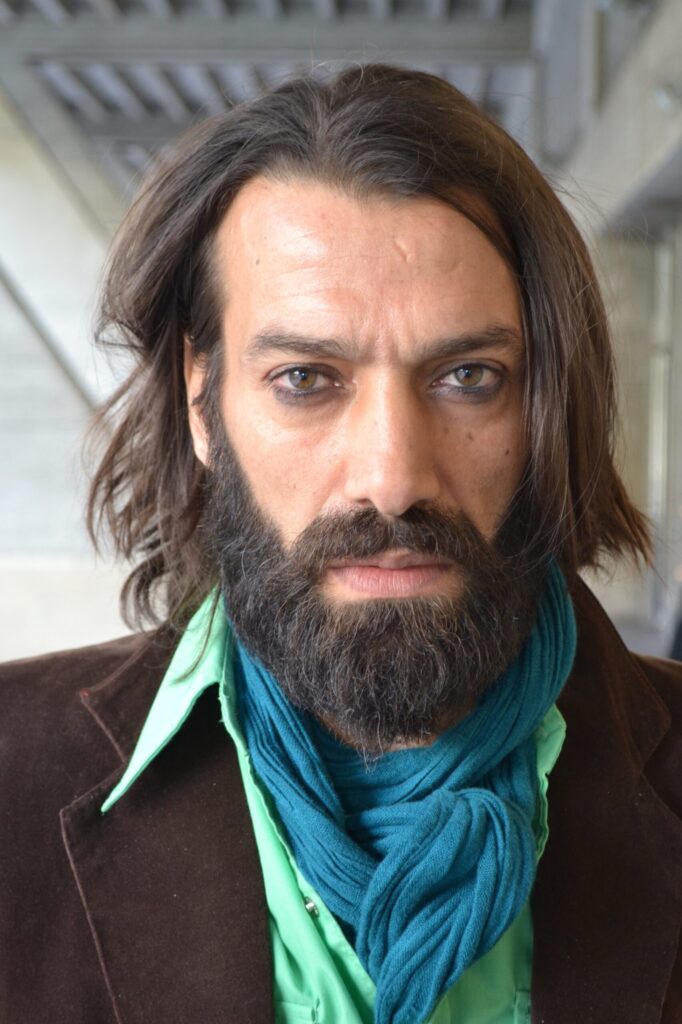

Ramzi Choukair is a Syrian-French actor and theater director. After obtaining his degree at the Damascus Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts (Acting section) in 1994; he did an internship (1995-1996) at the Avignon Higher Institute for Performing Arts Techniques as a stage manager. During that time, he had an opportunity to get training in techniques and scenography at the Peter Brook Theater in Paris, where he experienced the Brook’s directing method closely and had contact with the famous actors who had acted in The Mahabharata. In 2001, he obtained a Master’s degree in Performing Arts from the Paris VIII University. Parallel to his studies, he started a professional career as a lighting designer and stage manager in Syria, and was the technical director of the Damascus Arab Capital of Culture Festival in 2008. He participated in several festivals in France (Avignon Festival, Aix-en-Provence Lyric Art Festival), as well as other performances and theaters (Péniche Opéra, Palais des Glaces, Grande Halle de la Villette).

Ramzi Choukair. Photo Credit: Ammar Haj Ahmed

His first stage production ‘Al-Zîr Sâlem and the Prince Hamlet’ was adapted from two plays (Al-Zîr Sâlem) from the East and (Hamlet) from the West. In 2006, he cooperated with the well-known Syrian actor Abderrahman Al Rashi in the theatrical show Chitra Daughter of the King Rabindranath Tagor which was played at the Damascus Opera House. In 2007, he adapted two texts of Aristophanes and directed The Women Assembly which was performed by the fourth-year students of the Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts; the following year he recreated the play with male actors and presented it in Damascus and the Jean-Vilar Theater. In 2010 (in collaboration with the same theater), he created the Mediterranean Arts Platform “Al-Wasl” Festival. Between 2011 and 2013, he worked as a specialist in contemporary Arabic theater at Friche la Belle de Mai in Marseille. In addition to his multi-times performing at the Avignon Festival, most of his performances were toured internationally in Toronto, Edinburg, Berlin, and London. In 2016, he won the Helen Hayes Award for Best Actor for playing Jean-Baptiste in Salome, that was directed by Yaël Farber and created in Washington in November 2015.

In 2018, Choukair directed X-Adra performance which resulted from an artistic project that utilized theater, photography, writing, and singing as mediums to work with Syrian women detained in the prison of Adra between 1980 and 2015. The performance was based on the women’s personal stories and aimed to enable them to approach and process parts of their prison memories and communicate them, eventually leading to improving their living conditions. He directed a second performance Y-Saidnaya in 2019 with professional actors to portray the testimonies of Syrian prisoners in the infamous prison Saidnaya; the former detainees joined the actors on stage. The dramatic treatment of each story was based on individual and collective memory to produce a narrative that is closest to the truth and would inspire collective awareness for the protection of individuals.

The following interview took place by video call in Beirut/Marseille on the 5th of April 2021.

Najwa Kondakji: It is known that you are a skilled specialist in theatrical techniques, as it was your major study after acting. Could you elaborate on the importance of studying theatrical techniques? Do you consider yourself a professional in this field?

Ramzi Choukair: I understand my reputation as a technology specialist, but I prefer not to be recognized on this basis. With all I have done in this field, I never felt confined to it but always aimed to balance with my work as an actor and director between Syria and other countries. There is no doubt that my studies provided me with more technical and scientific knowledge of the performance composition on stage which guides me in deciding how to conduct the work.

I do not find myself reaching a specific level of professionalism despite my success in my studies in France and my achievements in Syria. Nonetheless, that helped me organize my thinking as an artist and answer questions related to the pieces that I am working on.

NK: Accordingly, can we say that the training you did with Peter Brook was not limited to performance techniques?

RCH: It was definitely not limited to theater technologies, even though I had not yet entered the world of directing at the time. I was surprised to learn about Brook’s working method with his team; he keeps his human simplicity even though he is a great theatrical artist. I found out that the distinguishing feature of Brook’s shows is their simplicity.

NK: How did that impact you? What did this experience with Brook change in terms of your perception or perspective of the theatrical performance?

RCH: The fear barrier of the great theatrical artist has broken. When I met him the first time, I asked if I could lean on the stage because I am trembling as I’m talking to someone who is considered a theatrical god. He smiled and invited me to be introduced to his actors. Half an hour later, he put his hand on my shoulder as if he had known me for a long time and said to his team: I introduce you my friend from Syria. This experience made me realize that human formation should be the center of our work and that the dramatic material that emerges and characterizes on stage is extracted from this human.

Well, I have always considered that I acquired my acting skills thanks to my professor and idol, Jamal Suleiman, who taught me at the institute. And I definitely gained the professional and artistic basis of directing from Peter Brook.

NK: The diversity of experiences is quite striking in your biography; you have worked with international artists and participated in many festivals. Why didn’t you stay in France after completing your master’s degree? It is known that the artistic horizons there are broader even though the opportunities need an extra effort to be obtained?

RCH: After I finished my first studies in France, I felt that a part of me remained there and I should return to it at some point. Later on, I got a scholarship from the Ministry of Culture, so I went back there for my master’s degree. Upon my return to Syria and since I received a government grant, I became a teaching staff member of the Institute’s acting department, and it was my first experience in directing.

At that time, preparations were made for the opening of the Opera House and I was appointed by the Institute to be its technical and artistic director. I put all my energy and knowledge that I gained in Europe and proudly provided a fundamental pillar for the place in terms of equipment, the organization process, and technical management in cooperation with workers to manage the technical affairs department. I think we have succeeded and done fairly well. Later, I could work in Syria and abroad.

NK: And how did you end up being in France? Did you go because of the war?

RCH: I was already there and decided to stay. The agreement with my French wife was to spend five years in Syria and another five years in France to maintain some kind of balance in living between the two countries. By coincidence, we were there when the revolution began in 2011, and since the end of 2010, I have not returned to Syria.

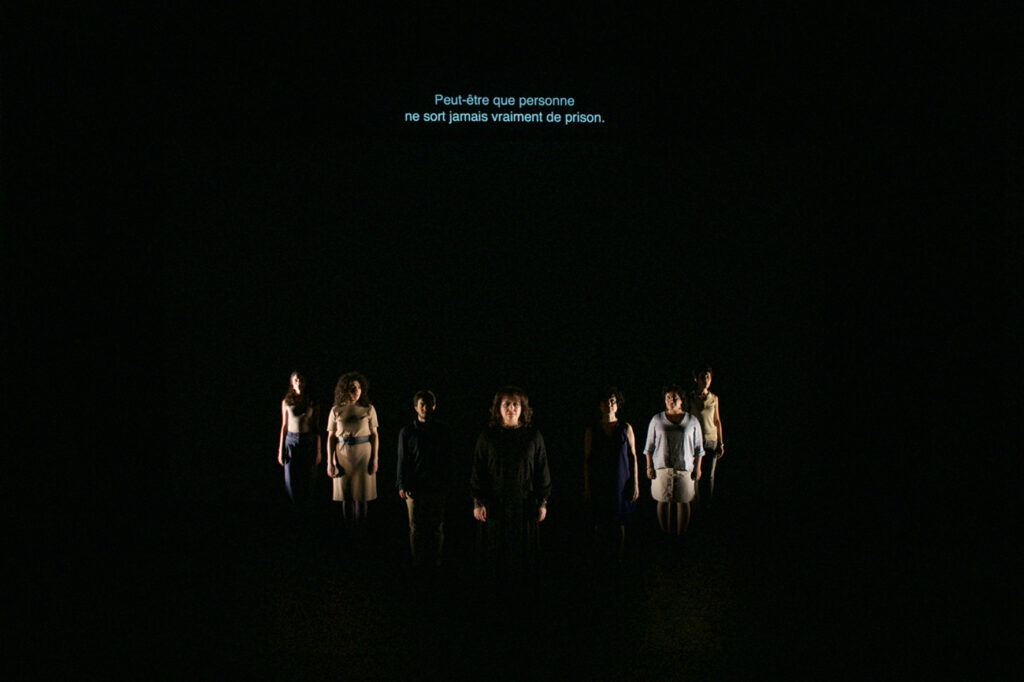

X-Adra 2018. Photo Credit: Ahmed Navi

NK: Since 2011, there have been many theatrical projects addressing aspects of the Syrian war which presented real characters (particularly refugees); most of these projects were funded and conducted by civil society organizations. Is X-Adra performance one of these?

RCH: No, it is my own. For a while, I was looking for any opportunity to contribute to the revolution by talking about the Syrian circumstances, the regime, the Syrian population and women specifically, aside from what I have already done of demonstrations, media work, and gatherings.

I got to know the first Syrian female prisoner 20 days after her release from prison while I was acting in a TV series in Turkey in 2015. I was very moved by her story, which inspired the idea of a show presenting the experiences or stories of these real women and their testimonies. After that, I began to compile new material by hearing and collecting the stories of these women in Turkey, France, and Germany. At first, I wanted to conduct the show with professional actresses, but then I thought, why not doing it with the women who told their stories.

NK: Isn’t that a big artistic challenge?

RCH: Of course, it was too risky to work with non-professional women actresses, especially in national theaters where performances were given to top French artists, but this did not prevent or discourage me from producing the show.

NK: In this context, I was drawn to the participation of the well-known Syrian opera singer, Lubana Al-Quntar, who didn’t only sing but performed a monologue at the end of the play, which added a dramatic dimension to her character. Why was the presence of Lubana distinct from the rest of the characters?

RCH: She is a symbol of the missing lady. Her dramatic role was to portray the prisoner’s voice, and not only the Syrian women. These ladies did not speak about the Syrian regime as much as they talked about their existence dilemma and ability to prove themselves in this life. This symbolism stripped the project of its locality, and the script was no longer only Syrian.

NK: Another character that invoked curiosity was Ali, who is a transgender person. Was the topic of transsexuality important to you? Or was there another dimension to this character’s presence?

RCH: What is striking about this character was that when she was a girl named Ola, she did not dare to declare her sexual orientation around her parents. When the revolution began, she was arrested in the women’s prison and was horribly tortured; her charges nearly led to her execution. In prison, she decided to declare her sexual identity and break this terrible taboo in Arab society. This was the first substantial challenge she faced with her own self, which was later devoted to the show. This personal dilemma tempted me to bring out those internal psychological obsessions on stage within a dramatic line without judgment, and let the recipients build their own conclusions.

NK: Working with former detainees is extremely difficult and psychologically challenging; when the tortured detainee reveals what happened to him on stage, he lives the experience all over again. How did you manage to deal with the ordeal during rehearsals? Was the role of theater here as a catharsis or a healing method for traumatized people? Or did they get over their torment? How did you deal with this issue on your side, and how did they do it?

RCH: I was fully aware of this sensitive point, and for that reason, we had a psychiatrist always available and ready when needed. He monitored us remotely in case someone had a breakdown, and it did happen that we needed him once.

I am convinced from my own experience that a human being is most likely not able to take the prison out of him, instead it remains a reality he carries inside wherever he goes. It is important to learn how to reconcile with it and to carry the past without considering it a burden, after all it is my memory, my life and I should preserve it. I am going to elaborate on this individual memory because it composes the collective memory that we need and share.

In addition to all this, I created good working conditions; we were able to make conversations together for a month and lived with each other until we got to the show.

NK: Isn’t this a huge and perhaps frightening humanitarian responsibility?

RCH: Certainly, but my interest in presenting their cases was more significant than any fear I initially had. Those people needed to tell their stories and wanted to be heard. The residency turned into a workshop, where we conducted physical and vocal exercises, memory stimulation sessions, and communication training on how to interact with each other while being on the stage. Later on, the ladies chose among themselves what stories to disclose, which formed the narrative produced at the end. In that sense, I was just the dramaturge reworking on their re-construction; the story was the preference and the crucial mechanism of the show.

NK: It is evident that the characters of the performance tell their stories without intense emotions, as an attempt to highlight the story itself. Was this done to avoid being portrayed solely as victims?

RCH: You are absolutely right! I have constantly directed and reminded them: You are not here to gain sympathy, nor beg for sentiments for the Syrian case; it is simply not what this experience is about.

NK: Can we consider Y-Saidnay performance as an extension of the first experience? What are the differences and similarities with the previous show?

RCH: After X- Adra, everyone wondered what could the next show be about? Thus, I decided to create content as a second part, after all the topics of the two shows are similar. I was interested in doing another experiment to maintain the quality of performance.

In X-Adra, the performer had a direct relationship with the audience in addressing and telling what has happened to him, whereas in Y-Saidnay, performers sometimes directed the speech to each other, in addition to the participation of professional actors on stage. The development of the art form and rhythm of the show was a collaborative task between the real personage and those professional actors.

I relied on the actual testimony of a Turkish detainee who spent twenty-one years in different Syrian prisons, and was kept in Saidnaya prison when the insurrection occurred in the same year as Damascus was declared a Capital of Arab culture. That rebellion was the backbone of the show where drama lines were inspired. It was a story within a story, and all the presented characters have had links with Saidnaya prison in one way or another. I took the stories and rewrote them, so the final script is my own.

Y-Saidnaya, 2019. Photo Credit: Salvatore Pastore.

NK: Conversely, there was a Lebanese character in the show, don’t you think it was out of context?

RCH: That character was created by me to reflect my perspective because I think we cannot talk about Syria without talking about Lebanon, as both countries almost share the same memory, and it should be noted that most of the play’s characters arrived in Europe through Lebanon. The presence of the Lebanese and Turkish personalities confirms my perception towards the regime; the issue is not a person in particular, but the whole system in the Middle East.

NK: How did the spectators feel about such a specific topic? Did it affect them, or did they consider it something they had nothing to do with?

RCH: They were deeply touched and even felt embarrassed. They could not believe that these women had lived these harsh experiences and were real characters, not actresses. People were truly amazed by them and wondered how they were still able to go on with their daily lives after all they had been through.

NK: I wonder about the reception mechanisms since the performers spoke Arabic and the audience read the subtitles during the performance. Doesn’t that hinder the interaction with the show? How did the performers (on their part) follow the instant reactions of the spectators when it did not reach the required level of interaction?

RCH: This question is often asked, but I must say that we relied on translation to convey the meanings intensively. We translated the play into a legible text that reflects a simpler version of the script for the audience to read and comprehend. Moreover, I tried to make musical or silent breaks to give the audience a slight pause from reading. The performers were aware of that point, and I asked them to stay focused on their performance and stick to the script. The magic that attracts people on stage is the speech that is heard, regardless of its language, even if it was in Arabic in this context.

NK: Wasn’t it difficult to convince French sponsors to produce such shows? How did the fundraising for your offers go?

RCH: It was tough to fund the first show since the actresses were unknown and did not have their own audience; similarly, no one knew the possible outcome of my work. It was my first directing experience with a national theater, not as an actor, and it is understandable that no one would risk offering me a job. But after the first show, the situation changed; as I mentioned earlier, most of the funding came from national theaters in Marseille, where I live, as well as the NGOs that engaged in the cultural sector. We were able to get many supporters, but with small amounts, some did not even exceed 5,000 Euros. Having said that, I do not interfere with the production procedures. It is the job of the production manager, the accountant, and the troop manager. With this one mind, I am currently preparing to complete the trilogy with a new show.

NK: Could you tell us what the third show is about?

RCH: In the third section, I want to give the tormentor the right to explain his version of events. I believe that by hearing his voice, we could determine the motives behind torturing these former detainees.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Najwa Kondakji.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.