Samara Hersch is a theatre-maker, director, and teaching artist from Australia. She received her Master’s in Theatre Practice from Victorian College of the Arts in 2010, as well as being awarded the British Council Realise Your Dream Award that same year. Following her apprenticeship under the direction of Bruce Gladwin, of Back to Back Theatre in Victoria, Australia, Hersch has directed and created numerous works in a variety of different media that have been recognized by artists and critics alike. She was a recipient of the Australia Council for the Arts’ Artist in Residency program at the City of Melbourne Arts and Participation, and she has been nominated for several Green Room Awards, Melbourne’s performing arts industry awards which recognizes achievements in theatre, winning Best Contemporary and Experimental Performance in 2017 for We All Know What’s Happening, a work that uses children to illustrate Australia’s unpleasant relationship with the island of Nauru. Hersch’s work is primarily focused on the importance of community, as well as making sure that marginalized groups get their stories told on the stage. Working within devised theatre, Hersch’s art is powerful, visceral, and profoundly imaginative. From shows such as Sex And Death, a part date and part photoshoot which explores how people change over time and with age, to Noa, which explores the intimate relationship between brother and sister in a bunker, she engages with universal topics in a transcendent and moving manner. She is currently based in Amsterdam, at Das Theatre.

Samara Hersch (above); Photo credit: Ponch Hawkes

The following is an edited version of an interview with Samara Hersch, conducted over the phone. Some of the questions have been edited for clarity.

What are you currently studying, since this is your second Master’s, yes?

[laughing] Exactly, yes. It’s quite a different program. This master’s I’m doing in Amsterdam actually used to be a residency for artists, who, after working there for a number of years, had wanted to go back and do some form of research, but now it’s become a university. It was originally funded by arts, private funding, and then educational funding, and at some point, it had to choose, so it became a university. Originally, this school was more of a residency for artists from around the world who had been working and wanted to take a break.

Do you have a lot of creative control there?

Totally. There are no teachers. It’s all peer-to-peer learning. There’s ten of us in my group: writers, theatre-makers, and we facilitate sessions for each other often, and we each have a private tutor, who guides us a bit. […] It’s a different structure than a university. It’s hard because I’m also still working on the side and it’s not much of a hiatus as maybe I would’ve thought it might be, which is my own fault. […] I think it’s also very interesting being in Europe, very interesting content for contemporary performance. There’s a lot of interesting things happening here on this side of the world. It’s really great to be around.

When did you know you wanted to pursue a career in theatre?

Very young, very young. I was directing in high school, I was also acting a bit, but somewhere, I decided I didn’t want to act. I think I realized I really enjoyed creating and writing, and then I met a theatre director named Bruce Gladwin, part of Back to Back Theatre, a really inspiring theatre company from Australia, and he once said to me, something along the lines of “when you’re devising, you’ve got every performance…you’re painting with lights, and with set, and with words, and with performers, so it’s not just a script. When you take a script and direct it, all these elements are your tools,” so it’s really exciting to think about…making work, like painting, with all these different materials. […] So I don’t work with a playwright, for instance, on a play. I work with performers and from there, we have a concept, a lot of improvisation, from there the material builds quite organically…it’s a really experimental process.

Who have been some of your biggest influences in regard to your work, as a director?

I mentioned Bruce Gladwin […] he’s been a huge influence on me, in terms of process and in terms of ambition and imagination. I still find him incredibly inspiring. I suppose artists like Pina Bausch were really significant to me when I was growing up. I was 16 when I first saw a show by Pina Bausch in Sydney, and I just thought, this is the most fantastic thing I had seen in my life. Amazing what you can do with just image, you know, and not narrative[…] Romeo Castellucci, an Italian artist, he had a huge impact on me as a person because he also makes…almost like visual art, in his performances. He’s really staging situations, but also working a lot with image and sound. He takes his time to really settle an idea and gives the audience a lot of time to fill in what is happening, in his kind of story.

Would you like to go into doing realism or do you just want to stick to what is going on now?

No, maybe as a side job, but no. My work is very much about working with non-professional performers. I work sometimes with actors, but also with different non-professionals, and that also changes the way one can work, and I really love that.

Do you prefer to work with non-professional performers than with actors?

It’s very different and I’ve always had an interest in people and in community engagement, on some level […] just meeting people…that inspires me. So, it’s less about a polished performance. I think actors are amazing, what they can do, and I often do work with professional actors as well, and it’s a really amazing craft. So, it’s not like it’s one or the other. I really like the meeting of the two. I find the chaos and the unpredictability very useful in that process.

You said you like to work directly with people. You are also a teaching artist, and have taught at Deacon University, Monash University, and St. Martin’s Youth Art Center. What is the most rewarding part about being able to teach young artists?

I think everybody has had different experiences of what is art and what is theatre, depending on what they’ve been exposed to at school or at home. I think it’s also about creating a curiosity around knowing that there are other things out there. And there are lots of ways one can relate to art, and lots of ways one can make art, and lots of ways one can express whatever it is one is looking for […] whatever is driving you. And I think I’ve always taught, in both Deacon and Monash, first-years, fresh out of high school and a lot of them have not seen a lot of contemporary performance, and now I’ll see them out at the same shows I’m at in Melbourne. They really have an appetite in making their own work and are really experimenting, so I think that’s always really nice to be a messenger in a way, in going “hey you should check this person out or, you know, expand your awareness.” […] Some of them now do internships, some of them now are makers of them, so now they work on shows. It’s really also community-building, all over town, but you know, some people realize it’s not for them. It’s a really hard industry to work in, sustainability-wise. It’s very difficult. It asks a lot. It’s very satisfying, but it asks a lot in terms of precarity, and I think one has to be really aware of that and how they can make it work. Sometimes it’s smarter not to do it. [laughing] I think it’s just very precarious. It creates a lot of stress to be an artist. You’re constantly having to create opportunities and find money and pitch yourself. It’s not a 9-to-5 job.

Going off what you just said, regarding theatre being so difficult, what was your most challenging show to direct or create?

I don’t know. They’ve all had different difficulties. [chuckling] I think a show I made, that’s called The Judgement [a show that deals with the relationship between father and son in Russia], was difficult, maybe because I didn’t have a lot of time. And I think I was experimenting with if I could make it work in a quick amount of time and I realized that I couldn’t, and I needed more time. So that was challenging because I felt–I didn’t feel so confident when I opened it, but it was ready.

Were you happy with the final product?

Aspects of it, but I felt stressed and in a way that didn’t feel so productive in the end. The stress was more paralyzing than–you know, stress can be exhilarating, but I think the stress I felt was more paralyzing because as a director you’re responsible for everyone. So yes, it’s really great to call all the shots, but you also have to bear all the responsibility, and that is difficult. But I also learned a lot from that show. I probably learned the most from that show, in a way. So, you know, you sometimes kind of have to challenge things to know what’s important to you.

The Judgement was one of your shows based on stories by Franz Kafka. Several of your shows have been inspired by or based on, works by him. What inspired you to adapt his work to the stage?

Have you read The Metamorphosis? It’s a really amazing short story that Kafka wrote about a boy who wakes up as an insect. […] You should read it. It’s a really amazing premise, in terms of metaphor […] people have adapted it to the stage before, and I was really curious what it means to stage, or try and represent, something as abstract as a man waking up, turning into an insect. […] There have been past productions that’s worked with people with really great physical skills, really physically trained, almost circus performers, who can act insect-like qualities and I thought, no I don’t really want to do that. I want to try something else. So, I want to look at maybe more the response of the family and how they change, more than how the man who becomes an insect changes. Because for me, it’s a lot about how we “other” people, how someone […] who was familiar can be unfamiliar. And I guess from that perspective, I’m thinking about any form of persecution that happens within a society, whether it’s Jews or Muslims or foreigners. It’s a sense of “you’re part of us, now you’re not.” That the rules can change, and society can kind of scapegoat different people, in different moments in history. So, I think I was really excited by this story, but also by the challenge of how to make it on stage, so that got me into Kafka. And it was when I was researching that I was reading a lot of Kafka. I just found him very contemporary, actually. I still think he is such an amazing writer and has really left his mark around the world in a really poetic way.

Such heavy topics, such as abuse and refugee immigration, were discussed in We All Know What’s Happening. What was your motivation to use children to tell this message?

I think there’s been such a complacency in Australia to respond to the refugee situation, and somehow through the media you see when children are implicated, there’s more compassion and people listen more, and so I think in one way […] kids understand human rights, ethics, a lot better than adults, they’re less jaded. So, I think it’s different when you’re hearing it from them. It’s really much more black or white. You also see it currently with the whole climate change. This young girl from Sweden, who’s leading the whole activism against climate change […] for her it’s really clear: it’s their future. And I think also in terms with the situation in Nauru and Australia, it’s a really dark chapter of our history and we can only really respond to it as Australians and so to think about, well, what type of an Australia are these kids inheriting and is that really fair for them to inherit this sort of dark chapter, and so it’s a lot of also thinking about the future and what kind of an Australia, what kind of a world are we handing over.

“Visual feast,” “marvelously evocative,” “deeply perplexing, and at times disturbing.” These are reviews from a variety of your work. Why do you feel your work tends to resonate with audiences and critics like this?

Why do people respond like this? I don’t know. I’m always surprised by how people respond to it. I don’t know how people are going to respond. I’m always happy when people do respond well. […] Just working from [laughing] how I see things, or how I feel things, and then you have to invite an audience […] It’s funny, I never really pay attention to–oh yeah, “visual feast”–what does that mean? [laughing] Yeah, I think the work is often quite unsettling, and always with intention. I’m really interested in the body, how one creates images in space and time. […] It’s so shit as an artist because you get all these great reviews and you really focus on the one bad one. That’s what you waste your time worrying about, and you often forget all the nice things people said. […] For me, I really knew that I didn’t want to make entertainment and I’m not really interested in trying to make everybody like what I do, so I think a lot of people don’t like what I do and I think, in a way, that’s good…because I think it was [Vsevolod] Meyerhold, possibly, who said–I’m going to paraphrase terribly–but something like, “if everybody likes your work, it’s entertainment. If no one likes your work, maybe it’s not really good. And if half the people like your work, and half the people don’t, then you’re making art.” And I’m totally paraphrasing badly, but however that quote has been passed down–making something that really creates some sense of feeling, with intention, whether they’re positive feelings or uncomfortable feelings or bored feelings…that’s okay. [chuckling] But I’m not interested in everybody thinking what I’m doing is great. It’d be amazing if that happened, but it’s not my intention. […] I think entertainment is also great thing, and really enjoyable, so I’m not against it, it’s just not what I make. I like being entertained as well. Sometimes I just want to be entertained. Again, I don’t think it’s good or bad, my work is just not entertaining…that I know [chuckling].

People have described your latest work, Dybbuk(s), as a horror to see and it made them really scared and uncomfortable-

[laughing]

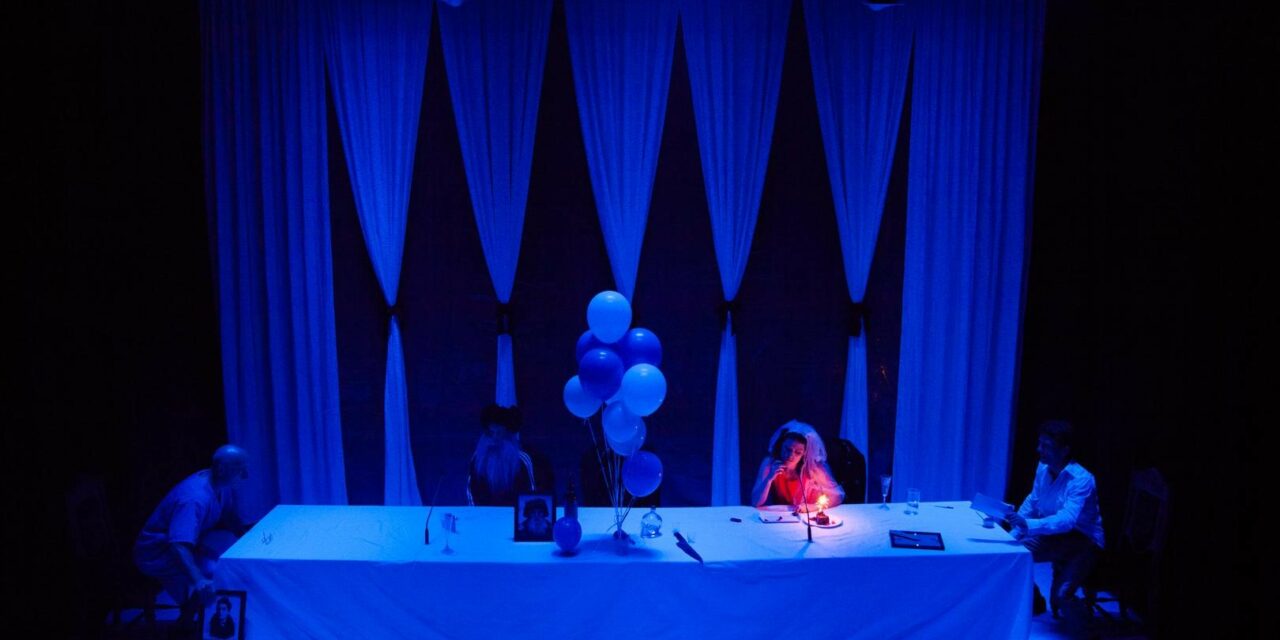

Dybbuk(s) (above); Photo credit: Pia Johnson

It draws upon S. Ansky’s early 20th century play The Dybbuk as well as Jewish folklore in general. Why did this story need to be told today?

Good question. I think for me, personally, I’m really interested in the legacy of Yiddish writers because so many Jews and artists died during the Holocaust. We lost a lot of their creativity and their art […] I think what tends to happen is that there’s a lot of nostalgia. You see Fiddler On The Roof playing everywhere–it’s one of my favorite stories, I love it, but unlike, say, Shakespeare or these other kinds of classics, Chekhov, that are constantly being readapted, and reimagined for contemporary times…I think what tends to happen–like with Fiddler On The Roof–it stays in a certain period.

And I was really interested in how to make contemporary moving stories, and really wrestle with the elements of today, and I think this idea of a dybbuk is really about the way that we live with the dead, in different ways, across religions, and across cultures, this way of being with the dead–particularly with women, through female bodies–and this I felt, very enigmatic.

But also, on a more political level, in Melbourne, Australia, there’s a lot of Holocaust survivors and a lot of them are dying. We’re really coming to a sort of end to that generation, and I think it felt very important to keep this language and keep this culture active, and not let it kind of pass with these people. So, I think that felt like an urgency for me to want to find access to this part of my cultural heritage. […] The work was a lot about the different ways that people are haunted, and I think maybe that’s why people were so disturbed by the work, because it really was playing with this other realm of reality that we all have some capacity to imagine–ghosts, or the dead, or you know, whether–without having to represent them, but somehow there is an awareness–that there could be other presences around and I think that’s what this work was really about–whether that’s just even history, them being with us in some way.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jeremy Moran.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.