The power of education as a tool for emancipation and democratic thinking has been the subject of a few productions of late in Spanish theatre. To Xavier Bobés and Alberto Conejero’s El mar. Visión de unos niños que no lo han visto nunca (The Sea. Vision of Some Children Who Have Never Seen It), first seen in 2022, and the initiatives of the Cross Border Project company over the past few years, it’s possible to add Raquel Alarcón’s new production: an adaptation by Aurora Parrilla of Josefina Aldecoa’s 1990 novel. This is not the first time the novel, inspired by the author’s mother’s journey as a schoolteacher across rural Spain and Equatorial Guinea in the 1920s and ‘30s, has been adapted for the stage. Paula Llorens solo version was first seen in 2022. Alarcón and Parrilla, however, opt for a more epic retelling with a cast of eleven moving fluidly to tell this episodic story across Pablo Chaves’s open set.

The clearest influence in Alarcón’s staging is Complicité, perhaps most concretely The Street of Crocodiles. The central design concept evokes a classroom, but the strength of Chaves’s set is that it is easily reconfigured to serve as a makeshift theatre, cinema and lecture hall. All are spaces for encounters and community, for learning and discussion. There is a sense of a society in construction in the mise en scène — nothing is finished or complete. The walls look as if they are being built — or a perhaps a premonition of what is to come with the destruction that follows the coup d’état and Civil War that consequently breaks out in 1936. Gabriela’s work is seen as part of an ethos that sees education as a vocation and a public service; a means of constructing a new nation. And it is this ethos that her daughter Josefina (Alarcón was born in 1926 and died in 2011) founds her own school grounded in vision of the progressive Institución Libre de Enseñanza (Free Teaching Institution, committed to cultural and social renewal) which closed in 2019.

Cultural initiatives promoting literacy and education in Historia de una maestra (Story of a Teacher). Photo: Geraldine Leloutre, Centro Dramático Nacional

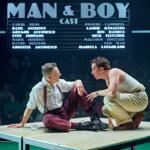

Josefina (Manuela Velasco) in dialogue with history in Historia de una maestra (Story of a Teacher). Photo: Geraldine Leloutre, Centro Dramático Nacional

Projections proffer the sense of an expansive landscape, with photographs and posters giving a strong sense of place and time. Nine performers take on numerous roles from children to bureaucrats, priests and fellow teachers. Julia Rubio provides a determined Gabriela, focused, defiant often clad in a green dress that aligns her with the vitality of Federico García Lorca’s rebellious protagonists. Manuela Velasco plays Josefina, an author effectively in conversation with her mother, Gabriela, across time and space. This is a mechanism introduced by the creative team which is not part of the novel, and it provides a dialogue across space and time. This framework of Josefina in dialogue with her mother holds the episodic action together. Josefina as an outsider is dressed more colourfully than her mother; her burgundy trousers and white shirt) present a more modern look that contrasts with the ochre-grey tones of Gabriela’s milieu. It is as if Josefina is in dialogue with history, engaging with a past that has shaped her sense of purpose and self.

Chairs are moved across the stage to configure different environments. Positioned on their sides, they point to turmoil; they are brought together to form a semi-circle as the community comes together to forge an action plan for the future. They are piled high to suggest a tower. Elvira Ruiz Zurita’s projections provide an epic sense of landscape: characters dwarfed by an environment carrying the legacy of oppression and dictatorship (rural Spain) and colonialism (Fernando Poo, now Bioko, part of Equatorial Guinea). There is clear evidence of class snobbery and racism from the ex-pats on the island of Bioko that want to control Gabriela. Misogyny also prevails: Gabriela is expected to toe the line. Teaching may be a vocation for Gabriela, but others just view it as a job for her to undertake without causing a fuss until she marries.

Props and furniture are swept across the stage to provide a sense of history whizzing past. Gabriela is inspired by the Misiones Pedagógicas (Pedagogic Missions); Federico García Lorca’s travelling theatre company La Barraca was part of this cultural initiative from Spain’s Second Republic to deploy art as a means of enhancing literacy. Art works positioned on the stage (including Velázquez’s Las Meninas/The Ladies in Waiting) provide the sense of a society where the arts were harnessed to define a sense of self.

At the play’s end, with Francisco Franco’s 1936 coup, Gabriela’s partner Ezequiel goes off to fight and defend Spain’s Second Republic. Shadow play on the stage provides a sense of the casualties as they fall during the early Civil War. The end brings no closure – just a new set of challenges.

This is an intelligent adaptation with David Picazo’s lighting playing a key role in evoking mood and change. The action’s bracing pace keeps the story progressing with Alba Blanco’s movement work offering a sinuous rhythm. I wondered if the exposition was a little heavy (at times the telling overshadows the showing) and the production, running at 2 hours and 20 minutes, could have used a little pruning. The episodes in Bioko felt repetitive with characterisation overly broad.

That said this is a production that is slick and well performed; in an era where Spain’s far right party Vox has sought to cancel cultural works, Historia de una maestra is a defiant statement on artistic freedom and the importance of education as the means for a nation to define its commitment to democracy in action.

Historia de una maestra (Story of a Teacher) was presented by the Centro Dramático Nacional and plays at the Teatro Valle-Inclán from 21 November 2025 to 11 January 2026.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.