The year 1994

In 1994, Nelson Mandela had been free since 1990, but a candidate in the upcoming elections that were set for April 26. This was going to be the very first South African election where the country’s people of all races were welcome to cast a ballot and was a predicted end of the white minority rule. That year, the best of the world media was in South Africa to witness history in the making, elsewhere Yemen was involved in a civil war, Formula One champion Ayrton Senna died during a race in Italy and in a small African country, Rwanda, on April 6, President Juvenal Habyarimana along with the Burundian counterpart Cyprien Ntaryamira, both Hutu were assassinated, triggering the Rwandan genocide against Tsutsi.

However, two days after the Rwandan genocide had set in motion, Kurt Cobain lead singer to rock band Nirvana was found dead, it would later be ruled a suicide but his legend status meant his death ruled the airwaves more than an African country with an interior misunderstanding.

94 terror

Over the years, people have concluded that the busy schedule of 1994 may have worked against innocent people that in the end lost their lives in genocide as the world was busy looking elsewhere.

“The World Cup was happening that year, Mandela, generally, by the time the world realized the genocide was more than an internal misunderstanding, a big number of people had died,” a Rwandan journalist once noted.

This year, they were 25 years since the incidents that are said to have claimed over half a million lives in 100 days and as it has always been, memorial events were held across the country. Over the years, all such memorials have been held under the banner Kwibuka which means “We Remember”, something that did not change with this year’s celebration.

Queen Moremi the Musical Immortalises Traditional Legend

However, as the years keep pilling, what the commemorations mean is always changing as per those involved in the activities, for instance, at 25 years, the entire group that took part in G25, a production that was staged at the memorial on April 12 were majorly born shortly before or even years after the genocide.

“It is hard to imagine what they think about commemorations that seek them to remember something they did not experience,” says a gentleman that referred to himself as Amos.

Amos was one of the many Rwandan nationals that had flocked the genocide memorial in Kigali on Friday afternoon, many armed with wreaths, the numbers of nationals here this week were obviously bigger than they are on ordinary days.

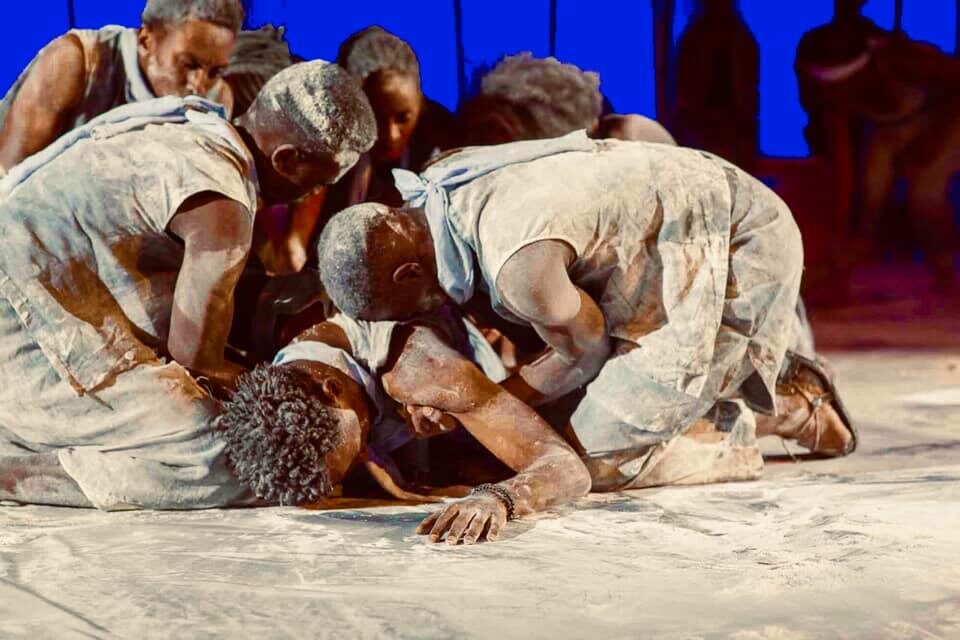

Just across, is a group of young people in final rehearsals for a production they are set to stage at an amphitheater located at the memorial. One by one, they go through their lines, dance moves and take positions one more time before the audience starts walking in at 6 pm. The production is based on three kinds of personalities that are all victims of what happened, those whose parents orchestrated the brutal acts, those that survived death as babies and those that have only read and heard about the genocide.

Born into the chaos

Shane Muhimanyi, a Rwandan actor based in London says that there is scientific proof that a child even in the womb can experience traumas a mother goes through. Muhimanyi was two years old when the genocide broke out that he (obviously) has no recollection of what exactly happened but remembers growing up with a man he later came to know as an uncle. For years, he believed this home and the people in it were his biological parents, until at seven when he had to join his father in London, it was at this time he learned of his mother’s fate, she had been killed. At the time Muhimanyi was born, it is believed the 1994 genocide plans were taking shape; President Habyarimana had started negotiations with RPF, a rebel group that was mainly made up of Tutsi refugees.

Ruth Bahali, on the other hand, was born in 1998, four years after the genocide to a mother that had survived.

“My mother at the time would tell me not to speak to some people and I could not really understand why,” she says. Even when she had heard a lot about genocide, things became clearer when her mum shared her story: “I got to learn more about the hatred and how people killed their families because they were different.”

Ange Elsie Ineza, 21, is not even Rwandan, a singer and actress, she moved to the country from neighboring Burundi in 2016. In 1994, before she was born, Burundi was one of the five neighboring countries that hosted many of the genocide survivors and Ineza had partly heard some stories in line with their plight.

“But my biggest source of information over the years have been stories that have been written and films made,” she says.

Yet these are just three of the over twenty man cast that brought to life a production that channeled a generation that is learning about its past while touring through it, those born outside the history and those that are still coming to terms with it.

How they relate

For a generation that was too young to understand, or born years after the chaos, it is easy for many to believe they do not relate with what happened in 1994. Muhimanyi, however, says that being outsiders does not mean that they do not relate. “It doesn’t matter where you end up in life, home is always home,” he says adding that it is difficult to come to terms with some facts that involved people murdering their families. Yet for Bahali, every time people tell her stories of what happened, she says she connects with the story more: “It is not just a simple crime that happened, it is a large scale conflict that even when you did not live through it, the stories told will make you experience it.”

For Mekha Ndayisenga, one of the many people that turned up for the shows, relation with the genocide has mostly come with his search for an identity. By 1994, his mother was pregnant with him and her life was threatened: “Growing up, I always believed that I was a survivor because of my mother.” However, in 2013, Ndayisenga met his father for the first time in Congo: “I remember asking him why he never comes home to Rwanda.” That is when he learned that his father had been in charge of security in one of the units, this discovery led him to wonder why people had been murdered in a place his father was meant to guard. After asking more questions and researching, he learned that one of his uncles used to leave home daily to slaughter Tutsis: “Apparently he used to promise my mother that it would be her blood that he was going to use to clean his machete at the end of it all.” Twenty-five years later, in search of his identity, Ndayisenga at times wonders whether he is a victim or a survivor of genocide but stands out to bridge the gap by talking about it and reaching out to survivors.

The production

The production that was witnessed by a packed amphitheater combines forms of art like poetry, contemporary dance, spoken word, and music. Besides the band that gave the entire show a rhythm, the cast was made up of people that were born during, slightly before and after the genocide. This was basically the reason why the producers intended to focus more on telling the story from their narrative as opposed to what is already known.

Hope Azeda, the founder of Mashiriki Foundation noted that working with a group younger or as old as the genocide was different: “Over the years, as an artist, you would come on set and start by memorizing where you were at the time it all happened.”

According to worldometer.com, about 60% of Rwanda’s population are young people, many of these have only heard about the genocide from a third party or worse an inaccurate Hollywood film.

“The genocide is a tricky topic, some parents are still hurting and thus do not talk about it that their children only learn a few things about it when they see their parents mourn in April,” says Yannick Kamanzi, one of the co-directors of the production.

Making matters worse, some of Rwanda’s young people are only revisiting their history after being born in Congo, Tanzania, Uganda, and Burundi, many of them revisit their history as a tourist because they too were told nothing by their parents. Azeda notes that this time, the questions they dealt with as producers were different, they had to deal with Rwandans that wanted to understand what exactly happened: “some actually do know a thing or two about it, but many are still discovering.”

In Rwanda, while commemorating, people try not to be in celebratory moods, for instance, people rarely clap, apparently, a group of boys earlier in the week almost got themselves in trouble after they took to the bar, drunk and celebrated a Barcelona victory over Manchester United in the Champions League. Maybe this could explain why even with a filled amphitheater, the silence of the audience was so loud. From punchlines and pros, the audience simply listened even to things that made them cringe. At times, it was just the actor’s breath we would hear amplified by their body microphones while other times, it was camera clicks.

The songs about keeping a fire burning, some too old for the performers and audiences ages, to spoken word about losing a mother, the cast spoke to someone in the audience. An audience member, for instance, lost a mother on the actual day the production was staged and noted that the speech on losing a mother spoke to her the most. It was thus surprising when at the end of the show, the audience lost themselves, clapped and on top of it all, gave a standing ovation.

Performing at the memorial

Simon Iyarwema, also a co-director of the production noted that this being a younger generation, there was no truth they could give them other than through art. Like Azeda, he also notes that this group had many questions, especially many wanting to know why it happened: “unfortunately, that is one question we too don’t have an answer to.”

The memorial has held a number of shows with most of them harboring messages of healing and reconciliation, thus, many believed that besides the timing, the venue too gave the production the right feel.

With motifs and collages like cloths, fire, and body movement the show closed with an original composition talking about a generation that doesn’t want to be defined by the past but one that is willing to reconstruct that past to protect a future.

With energetic moves, ridiculous hair color and costumes, they did not claim to know everything about the genocide, they were accepting to be schooled but at the same time reaffirming that they have something to say, in a way they know best, a way they know no world event will shut down like they did in 1994.

Kaggwa Andrew Mayiga is an Arts and Culture reporter, a trained theater, music and film critic. In the past, he has served as a jury member for various film festivals and is one of the co-founders of African Movie Night Kampala and founder of the annual Nteredde Documentary Showcase.

This article originally appeared in The African Theatre Magazine on May 22, 2019, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kaggwa Andrew Mayiga.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.