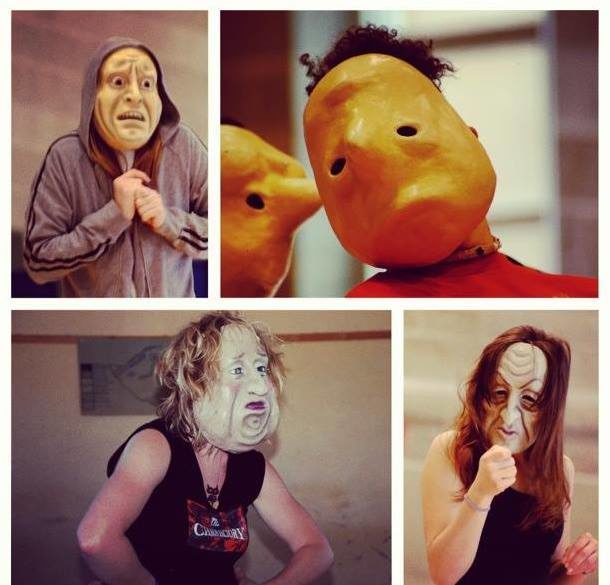

The Festival of Original Theatre (FOOT) is a 25-year-old annual event hosted by The Centre for Drama, University of Toronto. The theme of this year’s festival was “Sounding the Inner Ear of Performance,” and it was a timely event that reverberated with the booming acoustic trend in theatre. As David Roesner observes, “Sound and noise are currently experiencing a long-overdue renaissance in the discourses on theatre, theatricality and performance. After a disproportionate amount of attention directed towards visual and spatial aspects of culture, we are now seeing an ‘acoustic turn,’ to borrow Petra Maria Meyer’ s expression from her eponymous book, which listens to the noises and rhythms of a wide range of phenomena.”1 The festival embodied this auditory spirit of ‘listening to the noises and rhythms,’ curating some extraordinarily polyphonous panels and performances beyond the conventional academic conference. Brought by 60 individuals (including myself) and groups across the globe, the festival comprises musical performances, sound installations, academic papers, audio essays, performance-lectures, a blindfolded walking tour and a mask workshop.

Notable audio essays included Katharina Rost’s Shaping Music/Performance: About the Role of Listening in the Rehearsal Process, which invited listeners to discover how musicians explore hands-on approaches with actors and the director in a rehearsal room in Berlin; and Ximena Alarcón’s A Telematic Artistic Platform for Migrant Women, which constructed a sonic architecture that plunged listeners into the stories of eight migrant women, and the space between virtual connectivity and physical intimacy in our hyper-virtual world. These audio essays open up new territory, infusing performative elements with academic content. As non-representational as sound/music is, language often tries to describe or impose a meaning on top of it, to no avail. Therefore, an effective audio essay, incorporating the right amount of sounds and voices, resembles a verbatim theatre where you can hear the author’s words and the sounds from the environment directly. I find it both fascinating and challenging to listen to audio essays due to our dependence on visual and linguistic references, which they lack.

The festival encompassed multicultural and multidisciplinary topics, corresponding to the polyphony of sonorous dramaturgy (you can read a brief introduction to sonorous dramaturgy here). In the panel How Do We Listen? Modes of Auditory Reception, Jessica Watkin’s The Rhythm of Audio Description: Talking Through Theatre with an Unseen Observer and the Dynamics of Displaced Information tackled the existing audio description in Ontario theatre for blind persons, questioning the line between providing information and excessive/one-sided interpretation: how does an audio-describer craft the sonic experience for blind persons without imposing too many details and interpretations? In the panel Headset and Walking Aural Performances, Deniz Başar’s Down the Hill Entrusts analyzed this site-specific project about urban transformation devised by the theatre company Kumbaraci50 in Istanbul. Luis Carlos Sotelo-Castro’s Performing Listening in Colombia’s Post-conflict Context introduced his own walking audio project The Most Convenient Way Out (London), which invited participants to listen to the shattering voices of the youth of the rebel/terrorist group Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, FARC. In the panel Sound and Technology, Sophea Lerner’s LISTENERS AT WORK: A Delhi Listening Group Project (another audio essay) brought us to the streets of Delhi, to exploring the familiar sonic city space through an unfamiliar listening experience.

In the panel Sound and Gender Studies, Ryan Persadie explored how drag artists construct personas and identities during lip-sync performances, and the interplay between realness, character, and materialized body/voice. Adi Braun introduced (and performed herself quite mesmerizingly) the songs of the Weimar cabaret from the period around 1919 that led to the liberation of female self-expression and identities. In the panel Sound and Site-Specific Performances, Nicolas Royer-Artuso presented a strong political piece, a fictional performance of John Cage’s 4′33″ at an ‘open air festival’ in Baghdad. Artuso appropriated and played bombardment footage from CNN and a one-minute terrorizing recording of the war zone as part of his ‘performance’ that did not actually happen).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MuCYIB_AfEc

The panel Postdramatic and Interdisciplinary Sonic Dramaturgies featured assorted paper/performative presentations: Christopher Ross-Ewart and Frederick Kennedy (both MFA candidates from Yale School of Drama) showed their working processes as musicians explosively and sonically; I presented my paper Sonorous Dramaturgy: The Polyphony of Postdramatic Theatre, which searched for the musical roots of Polish theatre, and unpacked how Chorus of Women, an acclaimed theatre troupe from Poland, revolutionizes choral form to challenge theatrical and patriarchal norms; Dan Venning analyzed Elevator Repair Service’s aesthetics of sound and their iconic marathon production Gatz. In the panel The Sound and Cultures, Amanda Gutierrez and Jenn Grossman focused on the sonic explorations of urban segregation/integration and cultural immersion of several immigrant cultures in Chicago and New York City. Giorelle Diokno’s Diasporic Reverberations scrutinized the Filipino-Canadian performance High Blood, which infuses Filipino folk dance and ritual tradition with RnB and electronic aesthetics, reimagining a complex process of indigenous but urban identification.

The festival also featured some memorable performances in its Collage Concerts. Andrew Watts presented his Existentialism in Sound, a composition that eerily combines soloist parts with ‘algorithmically generated electronic textures’ and different rhythmic durations (quasi-randomly generated, as the artist says). The result is a flexible, dynamic piece full of acoustic surprises. Toni Lester collaborated with two local students to choreograph a piece accompanying her film/text/music/sound work exploring moments of transcendence. The Chemical Valley Project was an impressive documentary piece about the ongoing fight against energy infrastructure in Canada. It was presented by Broadleaf Theatre, a young company seeking to advocate for environmentalism through multimedia, innovative storytelling. In one evening, Brandon LaBelle’s The Church from Below took place in a church-renovated theatre. Based on the histories of the peace movement in East Germany, this installation performance piece wove together historical materials, documents, environmental sounds and recordings to signal and amplify the voices of underground resistance, ‘the hidden and the dispossessed.’

I list only a few presentations/performances above not because of my lack of interest in others but because of the sheer, rich volume that FOOT represents. For more information, please visit FOOT’s website: https://foot2017.wordpress.com

My question after the festival is: How far have the sounds traveled from their source? How much echo have they generated? It is unfortunate that the festival attendance was not ideal. I think it is a question not just for the curators of this particular festival but for all of us: If sound is intrinsically ephemeral, how do we, as artists and scholars, ensure that a broader range of audiences can hear clearly and attentively? How do we document and distribute sonic knowledge and information without losing its original profundity and vibratory qualities? In the era of the acoustic turn, these are the pivotal questions we must keep asking ourselves.

__

1 David Roesner, review of Dramaturgy of Sound in the Avant-Garde and Postdramatic Theatre, by Mladen Ovadija, Studies in Theatre and Performance 34.2 (2014): 186–87, https://doi.org/10.1080/14682761.2014.906953

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kai-Chieh Tu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.