Sonorous dramaturgy, a term borrowed from Eugenio Barba’s On Directing and Dramaturgy: Burning the House (2010), breaks down the hierarchy of the Aristotelian model and opens up new possibilities for evaluating the role of sound and music(ality) in theatre. Barba explains his understanding of ‘text’ in its pre-verbal sense and the necessity to develop a rich palette of sound for his acting training, epitomizing the essence of sonorous dramaturgy:

I was obliged to devise an arrangement of vocal actions and peripeteias which could enthrall the spectators independently of their comprehension of the words. Exclamations and calls, whispers, muttering, shouts, groans, laughter, sudden silence, crystal clear or hoarse tones, phrases modulated as nursery rhymes, psalms or traditional songs, intonations as litanies or animal sounds—bleating, neighing, twittering—were the basis for our sonorous dramaturgy. And, above all, during a dramatic climax, singing replaced words.[1]

This independence of vocal actions characterizes the spirit of sonorous dramaturgy—that sound is no longer an integral part of the semantic and thematic understanding of theatre. It escapes the unbreakable chain of linguistic signification, and steers audiences into an enthralling soundscape without the support of verbal comprehension, previously considered indispensable in a conventional or commercial theatre. In a talk in Frankfurt in 1998 about the ‘musicalization of all theatrical means,’ Eleni Varopoulou explains this independent attribute of ‘new music’: “for the actor, as much as for the director, music has become an independent structure of theatre. This is not a matter of the evident role of music and of music theatre, but rather of a more profound idea of theatre as music.”[2]

However, sonorous dramaturgy does not negate text or value sound and music over language. On the contrary, as Hans-Thies Lehmann points out, “In post-dramatic forms of theatre, staged text (if text is stated) is merely a component with equal rights in a gestic, musical, visual, etc., total composition.”[3] Therefore, sonorous dramaturgy elevates musical and sonic components to a status equal to that of other theatrical elements. Lehmann uses the psychoanalytical term “evenly hovering attention” (gleischschwebende Aufmerksamkeit) to describe this post-dramatic phenomenon.[4] We can say that sonorous dramaturgy operates upon the autonomy of sound and music(ality), which allows us to analyze sound per se—its materiality, corporeality, timbre and vibratory qualities, etc. As Barba elaborates on his concept of vocal actions:

I have always experienced the voice as a material force which sets things in motion, leads, shapes and claims: an extension of body. It manifests itself through precise actions provoking an immediate reaction in the person to whom they are directed. The voice is an invisible body which operates in the space.[5]

Barba’s understanding of music/sound as an extension of the body is crucial to analyzing the diversified perception(s) in theatre. The Swiss architect and theatre theorist Adolphe Appia has elaborated on the transferability of music—that musical quality can be embodied in body, gesture, mise-en-scène, lighting and architecture. Sonorous dramaturgy thus becomes a crucial tool for us to understand how the sound traverses through space, saturates body, scenery, and text and thus transforms their essential qualities.

As post-dramatic theatre thrives and conventional hierarchy disintegrates, we have to pay more attention to those invisible elements in the next wave theatre-making. Next time seeing a show, you can try to close your eyes for a while and ‘see’ whether the pure vibration of sound and music gives you an unprecedented sensual experience.

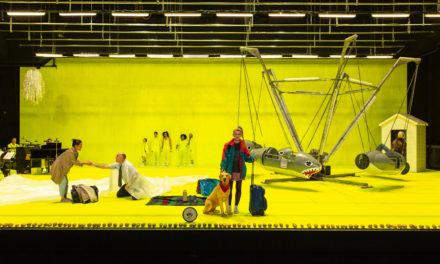

The Chorus of Women – Polish performance group modeled as a modern form of chorus theatre.

Notes:

[1] Eugenio Barba, On Directing and Dramaturgy: Burning the House (London: Routledge, 2010).

[2] Quoted in Hans-Thies Lehmann, Postdramatic Theatre (London: Routledge, 2006), p. 91.

[3] Ibid., p. 46, my emphasis.

[4] Ibid., p. 87.

[5] Barba, On Directing and Dramaturgy.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Kai-Chieh Tu.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.