Hummus is not appropriated hipster dip, it’s Palestinian food.

So argues Wally, a Palestinian-American, to his white ex-girlfriend Sarah early in Samer al-Saber’s new play Decolonizing Sarah: A Hurricane Play presented by Uprising Theater at The Den in Wicker Park. Hummus is a repeated device throughout the play, serving as a stand-in for the piece’s main struggle – that of convenient white understanding and appropriation of Arab culture and politics: getting just close enough without actually having to confront anything below the surface level.

During the COVID pandemic, Wally (Kal Naga) and Sarah (Maren Rosenberg) have retreated from their homes in Atlanta and Massachusetts, respectively, to an AirBnB on the Florida gulf, where – either because they didn’t realize or don’t care – a hurricane (Hurricane Bitch, as Sarah dubs her) rages outside. They have attempted to remain friends, but the vacation is a last try at salvaging the friendship, while both the storm and the pandemic essentially lock them in together. The storm provides an apt metaphor for the varying periods of calm and rage that punctuate their arguments over who should take responsibility for their breakup, their remaining feelings for one another, and Sarah’s casual physical relationship with a white East Coast rich boy named Charles Waldorf (Whitman Johnson), who is blissfully incapable of feeling a relationship outside of what he reads in a sex manual.

The play’s arc is slightly unmooring – which felt intentional and thoughtful – as it bounces back and forth in time from the present fight in the rental, to the development of Sarah and Charles’s relationship. The fact that it takes place both during the height of the pandemic and during Trump’s reign is a bit unnerving, and forces the audience to consider the heightened stakes by which we all navigate our personal and political relationships, and the fact that they are no more separable now than they were three years ago.

Al-Saber, who is Palestinian by heritage and a Canadian citizen, is a professor of theater and Middle Eastern studies at Stanford University, and his disdain for the frequent gobbledygook of academic discussion over simple action and empathy is evident throughout the play. Throughout the action, Wally no less than pleads with others to simply treat him like a human being rather than pitying his people at a distance or taking them on as a pet project for a wanna-be “white savior.” Meanwhile, Sarah’s business cofounder Melissa, with whom she is producing an app called “Feminista Universale” (or F.U.), coats her discussion in so much academic prose that she risks the appearance of lacking empathy for the very women she’s trying to help. When Sarah reveals she and Wally have broken up, Melissa is heartbroken. Although she shows her genuine care for Waleed, to her, cross-border feminism is the hot, marketable ticket, and Sarah’s relationship with Wally is Melissa’s pass to get some real progressive street cred. Can the app be a hit without a real live Arab to show off to investors? Cat Hermes gives a competent portrayal of the radical, but sometimes shallow, Melissa here.

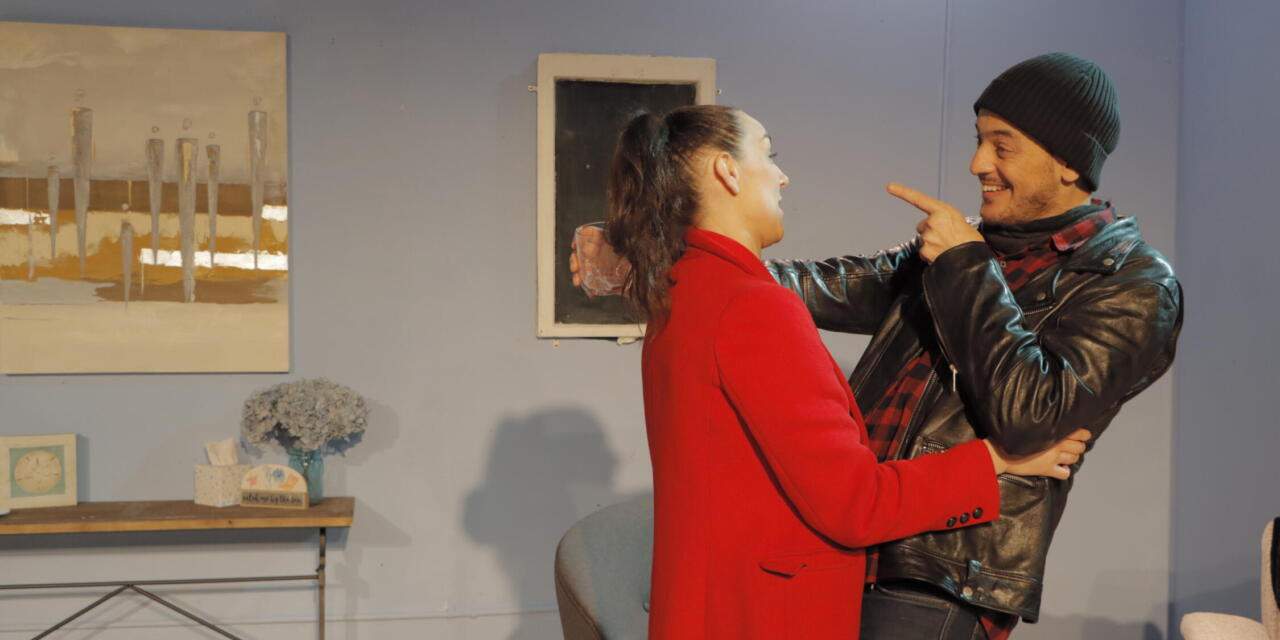

“That’s not what the F.U. is about.” From left to right: Cat Hermes (as Melissa) and Maren Rosenberg (as Sarah). Photo Credit: Samer Al-Saber

Sarah is caught between Wally and Melissa in one realm, and Wally and Charles in another. Maren Rosenberg capably navigates Sarah’s wrestlings with these conflicts, and ultimately we find that the conflict isn’t so much about who she’s going to choose than it is about deciding what kind of person she herself is.

Kal Naga as Wally (or Waleed, as we learn later in the play – Arabic for “newborn”) commands the stage as he veers from anger and incredulity in his conversations with Sarah, to his joking way of poking holes in sheer-thin activism, to trepidation and negotiation as he confronts a very real threat to his physical safety late in the action. Sarah is the one caught in the love triangle, but Wally feels like the central character here – prying, investigating, exploring his relationships and the motivations behind them, intentional or not. He’s the most dynamic, interesting character in the group, unsurprisingly – one imagines that the playwright really put his soul into Waleed, that Waleed is a mouthpiece for al Saber himself.

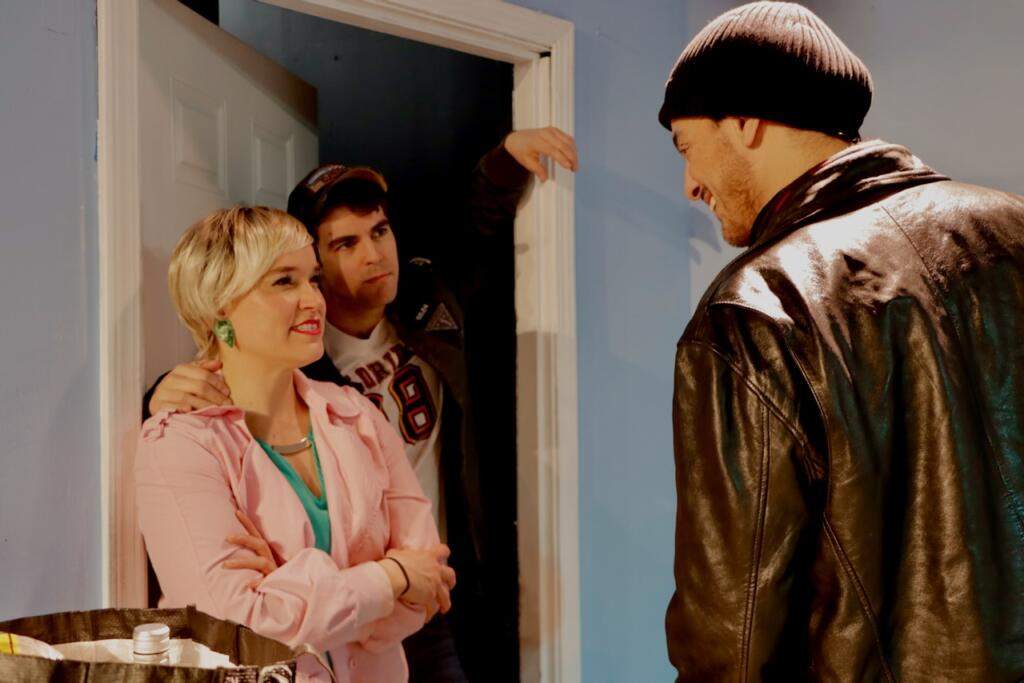

“I am sorry, sir. We have to look inside.” From back to front: Whitman Johnson (as neighbor), Cat Hermes (as neighbor), and Kal Naga (as Waleed). Photo Credit: J.C. Widman

And then there’s Charles Waldorf, played by Whitman Johnson. The character tugs at a few heartstrings – the tragedy of owning a large house in which to raise a large family, only to be abandoned by one’s wife before the fact – is palpable. Ultimately, Johnson’s portrayal is successful in that it’s similar to that of Melissa – the character is well-meaning and funny to watch, but ultimately surface-level, as al-Saber intended it.

Although Decolonizing Sarah was written by and about a Palestinian man, its suggestions about activism, solidarity, and “wokeness” could easily apply to feminism, the Black Lives Matter movement, etc. As white people, are we content to put on a show about how not-racist we are, hiding behind screens and apps and Facebook posts? Or does that give us just enough distance to keep us comfortable while playing at activism? And more importantly, what will we do when we have a choice to make – as Sarah does – about how far we’re willing to go for the people we write about on social media?

The play takes on a lot of issues and arguments in its 95-minute runtime (presented without intermission). Even as a critique of the dense academic subculture, the prose is thick, and it takes a fair amount of brainpower to grasp and follow all of the threads at stake. But this feels apt, as this is the messy, but very necessary, reality of how Sarah confronts the constantly-shifting dynamics of her intersectional politics, her business goals, and ultimately what’s in her heart. All in all, the production is largely successful in its heartfelt and engaging stab at confronting the audience with all of these questions.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Tim Hamilton.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.