There is not doubt that Marc Chagall (1887 – 1985) would have agreed with William Shakespeare that “All the world’s a stage /And all the men and women merely players.”

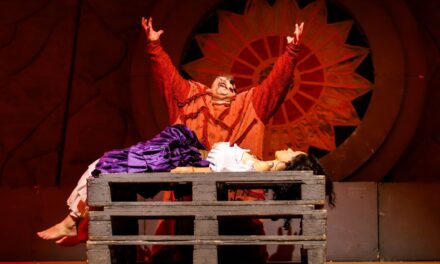

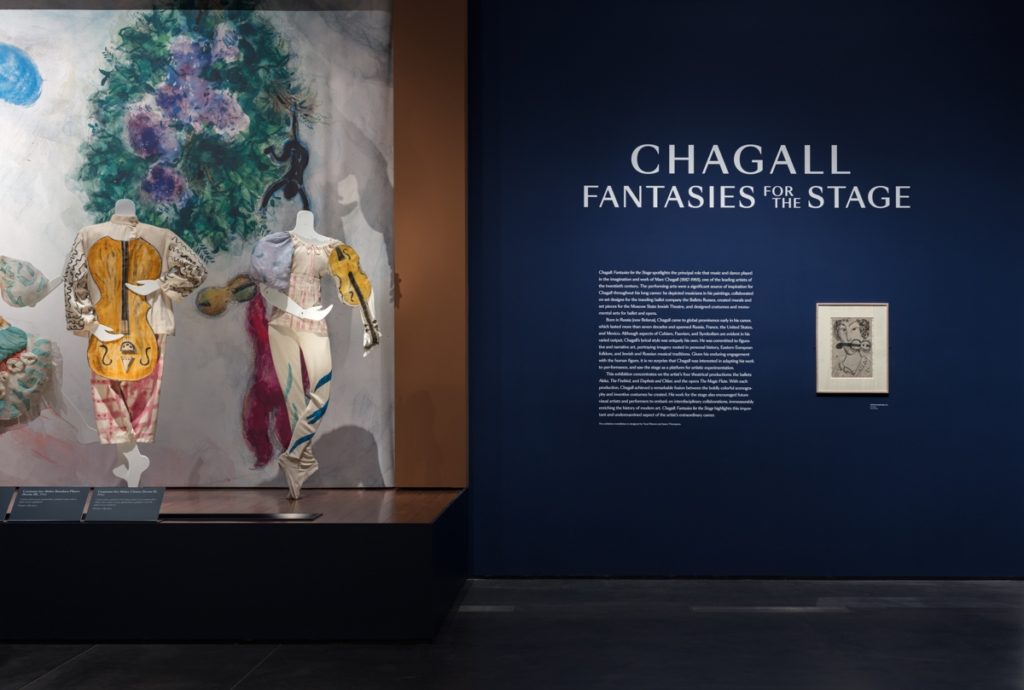

As one of the leading visual artists of the 20th century, the performing arts were a significant source of inspiration for the Russia-born artist throughout his long career from Moscow and St. Petersberg to Paris, New York and Mexico City and back to Paris. In the international exhibition Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage presented by the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, we are more than welcome to break through the 4th wall to meet the characters he created to serve four of the great musical compositions ever to be set for the stage: Tchaikovsky’s Aleko (Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, 1942), Stravinsky’s The Firebird (Ballet Theatre of New York, 1945), Ravel’s Daphis and Cloe (Paris Opera Ballet, 1959), and Mozart’s The Magic Flute (New York City Opera, 1967 for the opening of Lincoln Center). We are in fact encouraged to become infected through the sights and sounds of the exhibition and engage with the innovative spirit through they were conceived and executed.

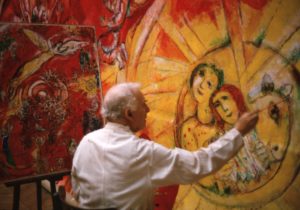

Marc Chagall working on the panels for New York’s Metropolitan Opera: The Triumph of Music, Atelier de Gobelins, Paris, 1966, art © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, photo © 2017 Isiz-Manuel Bidermanas

The performing arts were a significant source of inspiration for Chagall throughout his long career: he depicted musicians in his paintings (a number of famed oils are also included in the exhibition, as well as many gouaches, drawings and other preliminary illustrations that informed the finished works). Chagall collaborated on set designs for the traveling ballet company the Ballets Russes, created murals and set pieces for the Moscow State Jewish Theatre, and designed costumes and monumental sets for ballet and opera, as well as Lincoln Center’s famed tapestries and the mural in the ceiling of the Paris Opera House. His granddaughters, Meret Meyer and Bella Meyer, in Los Angeles for the premiere, described the artist and his collaborators, including their mother, Ida, as having enormous “fun” in the process of undertaking the multi-year projects.

Chagall’s unmistakable visual vocabulary — characterized by vivid colors, soft lines and deeply emotional characters, most of whom — even the monsters — seem to be smiling! — enables him to conjure for our pleasure many familiar friends and introduce us to new beings who inhabit his imagination and, through that, our world, too. This is the magic of great theatre art. As one who by the necessity of economic realities usually is ushered by valkyries into my seat in the heights of great opera halls, I was so happy to be up close and personal with these characters. This is the greatness of the revolutionary spirit of Chagall.

Chagall came to global prominence early in his career, which lasted more than seven decades and spanned Russia, France, the United States, and Mexico. Although aspects of Cubism, Fauvism, and Symbolism are evident in his varied output, Chagall’s lyrical style was uniquely his own. He was committed to figurative and narrative art, portraying imagery rooted in personal history, Eastern European folklore, and Jewish and Russian musical traditions. Given his enduring engagement with the human figure, it is no surprise that Chagall was interested in adapting his work to performance, and saw the stage as a platform for artistic experimentation. But mostly it was the beauty of the music that inspired his adaptation of color, form, and line. His characters, whether human or beast, fantasy or historically mirrored, serve their respective stories while challenging us to take them literally to heart.

With each production, Chagall achieved a remarkable fusion between the boldly colorful scenography and inventive costumes he created. His work for the stage also encouraged future visual artists and performers to embark on interdisciplinary collaborations, immeasurably enriching the history of modern art.

The exhibition Chagall: Colour and Music (January 29–June 7, 2017), was initiated by the Cité de la musique – Philharmonie de Paris (October 13, 2015–January 31, 2016), and La Piscine – Musée d’art et d’industrie André Diligent, Roubaix (October 24, 2015–January 31, 2016), with the invaluable support of the Chagall estate. LACMA’s presentation is organized by Stephanie Barron, senior curator of modern art, together with the museum’s costume and textiles curators. Los Angeles based opera director Yuval Sharon and projection designer Jason H. Thompson created the exhibition design.

The exhibition includes 11 costumes and 18 preparatory studies from Chagall’s production of Aleko, 8 costumes and 32 works on paper for The Firebird, 8 costumes and 28 drawings for Daphnis and Cloe, 14 costumes and 16 sketches from The Magic Flute. In some cases, Chagall was painting details on the costumes while the actors were in rehearsal to capture the appropriate dynamic movement and gesture. Chagall also worked closely with scenic designers, engineers, and others to realize his concepts for the works’ production values.

Augmenting the exhibition is a series of video interviews featuring contemporary artists, costume designers, and opera professionals, selected reviews of Chagall’s productions, musical selections from the respective performance works, archival photographs and extant film/video documenting productions. Projections of Chagall’s monumental theatrical curtains and articulated mannequins bring the works to life. The lavishly illustrated exhibition catalog, Chagall and Music, edited by Ambre Gauthier and Meret Meyer, is published by Editions Gallimard, with versions in French and English.

Installation photograph, Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage, from Aleko, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, July 31, 2017–January 7, 2018, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris, photo © Fredrik Nilsen.

Installation photograph, Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage, from The Magic Flute, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, July 31, 2017–January 7, 2018, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris, photo © Fredrik Nilsen.

Installation photograph, Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage, from The Magic Flute, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, July 31, 2017–January 7, 2018, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris, photo © Fredrik Nilsen.

Installation photograph, Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage, from The Magic Flute, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, July 31, 2017–January 7, 2018, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris, photo © Fredrik Nilsen.

Installation photograph, Chagall: Fantasies for the Stage, from Daphnis and Chloe, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, July 31, 2017–January 7, 2018, © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris, photo © Fredrik Nilsen.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Lauren W. Deutsch.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.