Kalkuta Republik Choreography Serge Aimé Coulibaly; music Yvan Talbot; inspired by the political thought of Fela Kuti; A production of the Faso Danse Théâtre, Halles de Schaerbeek (Bruxelles).

Born in Burkina Faso, Serge Aimé Coulibaly established his professional career in Africa. He moved to Europe in the early 2000s to re-invent himself as a European dancer and choreographer, now working in Brussels and Bobo-Dioulasso at the same time. In his subject matter and artistic devices, Coulibaly remains the patriot of his native country; he believes that an artist must remain the servant to his/her community. In his criticism of contemporary Africa, Coulibaly tirelessly asks one question – what role should or can play an artist in today’s charged world? His choreography, his dance, his personal presence on stage is Coulibaly’s response to this question.

This response transforms Coulibaly’s politics into poetry and philosophy, it brings to focus the divided self of an artist whose life style and whose audiences have become international Kalkuta Republik is Coulibaly’s most recent creation. Inspired by the life, the work, and the political activism of a legendary South African musician, Fela Kuti, it features an ensemble of six dancers lead by Coulibaly himself. An exploration of music, space, and movement in two parts, it speaks both about contemporary Africa and Coulibaly’s personal journey of exile. To become a real person, perhaps someone else, Coulibaly says, one must leave his native place. The consequence of this departure is one’s solitude – a necessary condition to make art and a curse all artists share.

Invited to present his work at CLOÎTRE DES CÉLESTINS in Avignon, Coulibaly found himself spellbound by this 14thcentury space that features two magnificent trees as part of its natural décor. The projections featuring images of African unrest and world military disasters normally constitute Kalkuta Republik’s scenography. For Avignon, they were diminished on purpose. The ambiance, the texture and the grandeur of CLOÎTRE DES CÉLESTINS dictated the atmosphere of this production, which became more about the solitude of an artist than, as Coulibaly thought it would be, a manifestation of his criticism of contemporary African politics. Still, the energy of this political project was not lost.

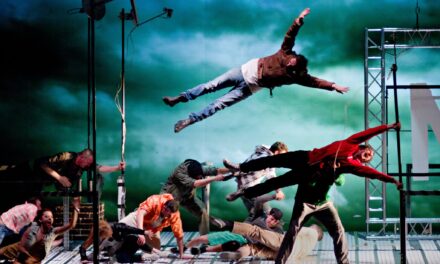

The first part, Coulibaly explains, is imagined in black and white, it is “the world of today, the fear, violence, and indifference that always seem to catch up to us.” It is also about how an individual finds his/her place in a group: what begins as an ensemble presentation of people exploring their separate solitudes, unfolds, with Coulibaly’s appearance on stage, as a dialogue these individuals. This new individual comes in as a connector between these people. Sometimes he is a conductor of this disjointed orchestra, sometimes he is a musician playing a first violin whose own movements are reflected in the movements of the others. For Coulibaly, this part “reminds us that everything is connected, that what’s happening far away from us can also have a real impact on our own lives.”

The second part takes on new colors. It reveals the world in chaos, its absurdity, and madness. Here a broken individual is shown from the outside, subjected to the ugliness of the world that has caught up to him and hurt him badly. Aesthetically, Coulibaly says, this part draws on the Shrine, a temple where Fela Kutti used to pray with the audience, “but also a night club in which he performed shows. It was a place where hope and ugliness once echoed in the world, a place conducive to political awakening. The walls of the Shrine were covered in sentences, words, and images.”

In the center of this political manifestation is the same lonely and broken individual, seeking peace within himself and within his community and the larger world. The music of Yvan Talbot underlines this message: echoing the eclectic palette of Fela Kuti, what is known as Afrobeat, where pop and jazz, funk and rock, evoke a sound score of African chants and percussions. At the same time, drawing on the work of contemporary dance visionaries, including Pina Bausch, Alain Platel, and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui, Kalkuta Republik remains deeply personal to Serge AiméCoulibaly’s artistic and philosophical program. To me, Coulibaly says, dance is a march, always personal and always political; “it’s the march of the world, the nature of humanity. What’s great about marching is that it has the capacity to change the world. The march itself is transformational: the marchers who come to a country will contribute to the building of that country for a long time to come. That is the reality and the hope of humanity. It’s also the topic of this show, which is a sort of endless march that becomes a state of trance.”

19 – 25 July, 2017

With Marion Alzieu, Serge Aimé Coulibaly, Ida Faho, Antonia Naouele, Adonis Nebié, Sayouba Sigué, Ahmed Soura.

Reposted with permission from CapitalCriticsCircle.com

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Yana Meerzon.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.