El día del Watusi (The Day of the Watusi) gets a second outing at the Teatre Lliure. First seen in the 2023/4 season at the Lliure’s Gràcia venue, it now plays in the larger Montjuïc Sala Fabià Puigserver. Francisco Casavella’s cult 900-page novel, published in three volumes between 2002 and 2003, has been adapted by Iván Morales into a three-part play that tells the story of Barcelona’s transition to democracy through a modern Don Quixote (Fernando Atienza) and Sancho Panza (Pepito el Yeyé) who on a fateful day, 15 August 1971, think they have seen the body of the legendary criminal Watusi floating in Barcelona’s harbour. Spain is in the final years of Franco’s dictatorship and Fernando and Pepito live in the Montjuïc slums that will subsequently be refashioned into the slick new quarters of an expanded Olympic quarter of the city. The Sala Fabià Puigserver’s expansive stage has been reconfigured to provide a four- and half-hour performance that draws on movement and music. Jose Novoa’s open stage looks like a concert rehearsal room, with a guitar, keyboard and drumkit. Music underscores the action with the actor-musicians shaping mood and driving the pace of the piece.

Part 1 sees the teenage duo, Fernando and Pepito, trying to work out what do with their new-found knowledge that local villain Watusi has, to the best of their knowledge, perished. They can’t be sure, but they believe he has and that is enough for the intrepid duo to hit the neighbourhood with this hot-off-the-press information. Fernando steals cars and a life of petty crime awaits. Guillem Balart – who played Fernando’s sidekick Pepito in Morales’s earlier 2023 staging — here takes on the role of the edgy protagonist. He’s a lean, sneaky presence, darting around but not always able to pick up all the implications of what’s happening on the ground. He’s a man in a hurry — his legs run across the stage in a scissor-like movement — but unsure as to where he is heading. Pepito is keen to keep up with Fernando but again not always sure of what the situation demands and in Artur Busquets’ intelligent performance, knowingly creates moves from the iconography of Cervantes’ put upon squire. “Que poca cosa son las cosas” (how insignificant things are) observes Pepito.

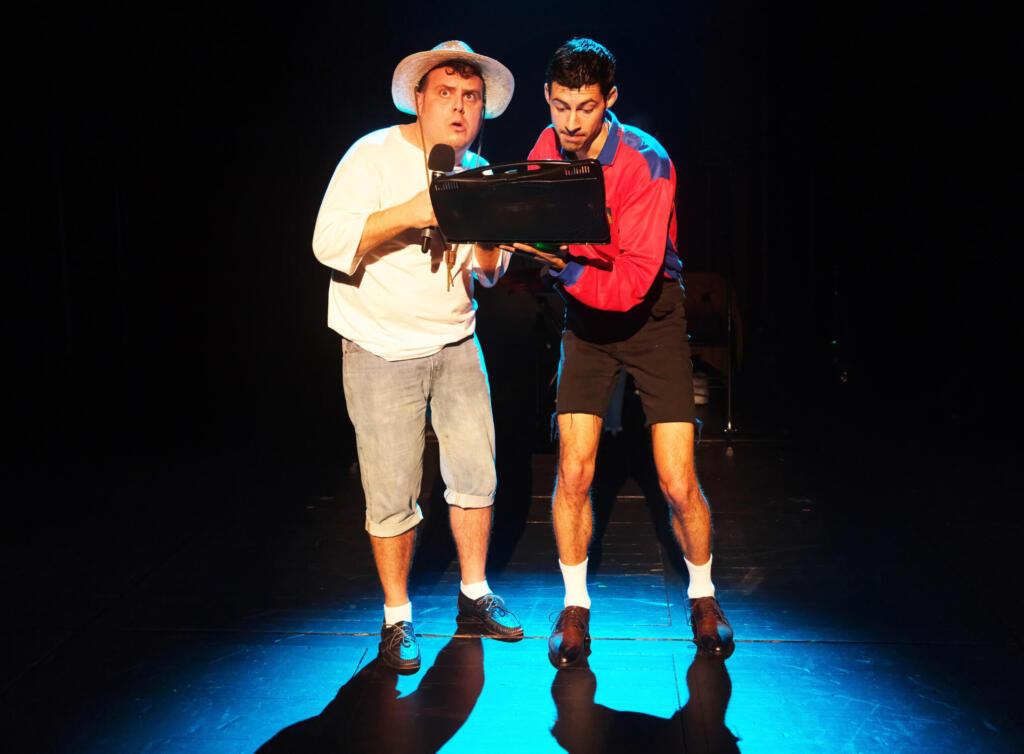

Fernando and Pepito, two adolescents trying to solve the mystery of the corpse in the harbour in Part 1 of El día del Watusi (The Day of the Watusi). Photo: Juan Miguel Morales

Fernando and Pepito may want to see themselves as astute detectives — Holmes and Watson also come to mind in the antics of this double-act — but they can’t quite pick up that Julia, the daughter of the neighbourhood’s boss, Celso, has not been killed by Watusi but by her own father after a long and horrific history of abuse. The information only comes to light in the performance’s final section – showing how little Fernando and Pepito knew of what was really happening in the neighbourhood.

Hindsight is a valuable commodity in Morales’s staging. Part 2 sees Fernando move into a new home near the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona as his mother secures a job as a doorkeeper in an apartment building and then marries the good-meaning but monosyllabic Carmelo; the family expands with two new younger siblings for Fernando. It’s 1977 and the country is in transition. The microphones sported by the characters in Part 1 are no longer in evidence, but Fernando continues to make his voice heard. He sees an opportunity when he is contracted by his boss, fixer Boris, to help teach the aspiring politician and businessman Tomás del Escudo’s mistress, Tina, to drive. Tomás is in the midst of setting up a new party, Liberal Ciudadado (Liberal Citizen) to keep hold of ill-gotten gains during the Franco years. The message is one of transformation, but the ethos is on maintaining the status quo. Aristocrat Don Jaime de Vilabrafrim is placed as the titular head (his palms greased by Boris to toe the party line) but it is Tomás who is calling the shots. Tomás wants respectability as a married family man of eight daughters but can’t let go of Tina. When Tina disappears and Boris’s past history of violent behaviour is revealed, the political party begins to fall apart. Corruption couldn’t keep the party legit or buy popularity, and in the end the secrets around Boris’s sadism – he is a suitably menacing character in Anna Alarcón’s prickly performance — sow a culture of corruption and danger that brings the party down.

The figurehead of the Liberal Ciudadano party Don Jaime, surrounded by Madrid opportunities López y López and Pérez y Pérez in El día del Watusi (The Day of the Watusi). Photo: Juan Miguel Morales

The action is fast and furious in Part 2; alcohol and cocaine flow freely and hedonism is the order of the day. Tina charges around the stage, knowingly manipulating Tomás because she is aware of his obsession with her. Boris dishes out bribes as if it were the most ordinary thing in the world. Anna Alarcón captures his sadistic temper as a dangerous man whose past comes back to haunt him. Boris is one of the many assassins of the Franco regime who reinvented themselves anew within the early years of Spain’s democracy, because they were allowed to. At the end of Part 2, Fernando runs away, suspecting that Boris and Tomás plan to do away with him.

Part 3 sees Fernando still in hiding; the stage is cluttered and messy, and an altogether more languid pace takes hold. The “pleasure at all costs” principle of Part 2 has taken its toll. Fernando still fears vengeance at the hands of Boris and Tomás. He eeks out a living as a petty drug dealer. Part 3 has something of the atmosphere of a stupor – as if Fernando’s present is now in slow motion. Fernando’s girlfriend Elsa is an addict, determined to keep the worst of her habit from Fernando. She stumbles and lies; she wants Fernando to help her get a new flat from her father to be able to sell it to fund her habit but can’t manage her addiction to pull it off successfully. In the end she leaves their shared flat in El Ravel, opting for prostitution to fund her out of control habit.

It’s 1986 and Barcelona is a candidate for the Olympic Games. Only Fernando and Elsa are on the sidelines of the brave new Barcelona. Around 25,000 are thought to have died in Spain from heroin overdoses between the late 1970s and the early 90s with 100,00 contracting HIV through intravenous drug use. Morales captures the other side of democracy’s early years. Dora — an acquaintance from the neighbourhood — reappears; she was a presence in Part 2 posing as a Venus for a painting for Tomás. She too has patched together a life of hustling, aware of their past shared history in a neighbourhood that time has forgotten. She tells him of Julia’s death at the hands of her violent father in 1971. Watusi was a convenient excuse for all to allow Celso to cover his tracks. Fernando was nowhere near as savvy as he thought he was. History might not be what we remember it to be.

Morales finds a rhythm for each of the piece’s three parts. From the lithe physical energy of the curious opportune boys in Part 1 to the frantic attitude of Part 2 and the slurred pacing of Part 3, the action progresses to leave Fernando suspended in an existence where he has failed to find his place. As with Ramón del Valle-Inclán’s Bohemian Lights, a tragicomedy where absurdism is all that awaits its out-of-joint protagonist, El día del Watusi also has something of the grotesque qualities of Valle-Inclán’s 1920 esperpento classic.

There is much to admire in high energy performances where six of the seven actors take on multiple roles: Anna Alarcón excels as the toxic Boris and a nasty neighbour in Part 1; Vanessa Segura as Fernando’s mother and the pompous aristocrat don Jaime de Vilabrafim shows a lovely sense of comic timing; Artur Busquets offers a picaresque Pepito and the anodyne Madrid-based Pérez y Pérez, hoping to forge an alliance with the Liberal Ciudadano party; Raquel Ferri as the pragmatic Tina and the addict Elsa gives an unsettling edge to each of her characters; David Climent’s lithe characterisations include the seedy Tomás del Escudo digging his own political grave as he insists on singing the shocking party anthem and the singer José Feliciano delivering a slick radio performance; Eduard Alves as the accomplice to Pérez y Pérez (the appropriately named López y Lópéz) is also very funny – he also shares credit for the music and sound. Toni Ubach’s lighting provides something of a surreal landscape for the action – the giant W of Watusi as a fluorescent light hovering over the stage and threatening to crash down on Fernando at any moment. It’s a constant reminded that Fernando has never been able to escape the day of the Watusi.

Casavella died in 2008 but his eponymous novel has been given a new life by Morales and his artistic team. It has played to packed audiences at the Lliure, the staging now broader and bigger than in its earlier iteration for the smaller stage of Gràcia. Madrid dates await in 2026.

El día del Watusi (The Day of the Watusi) was presented at the Teatre Lliure Barcelona from 20 November to 14 December. It plays at Madrid’s Teatros del Canal from 4-8 February 2026

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Maria Delgado.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.