I wasn’t prepared for Victor, Edgar Oliver’s latest one-man show, directed by his longtime collaborator Randy Sharp, at Axis Company. The description of the show put me on edge: “In Victor, Edgar Oliver unravels the details of his nearly twenty-year friendship with Victor Greco, a mentally ill homeless man.” Judging from that, I expected the show to be one-sided at best, horribly exploitative at worst. The stories non-homeless people tell about homeless people are never stories about homelessness, they’re stories about discomfort. And everybody in New York has pockets full of these stories.

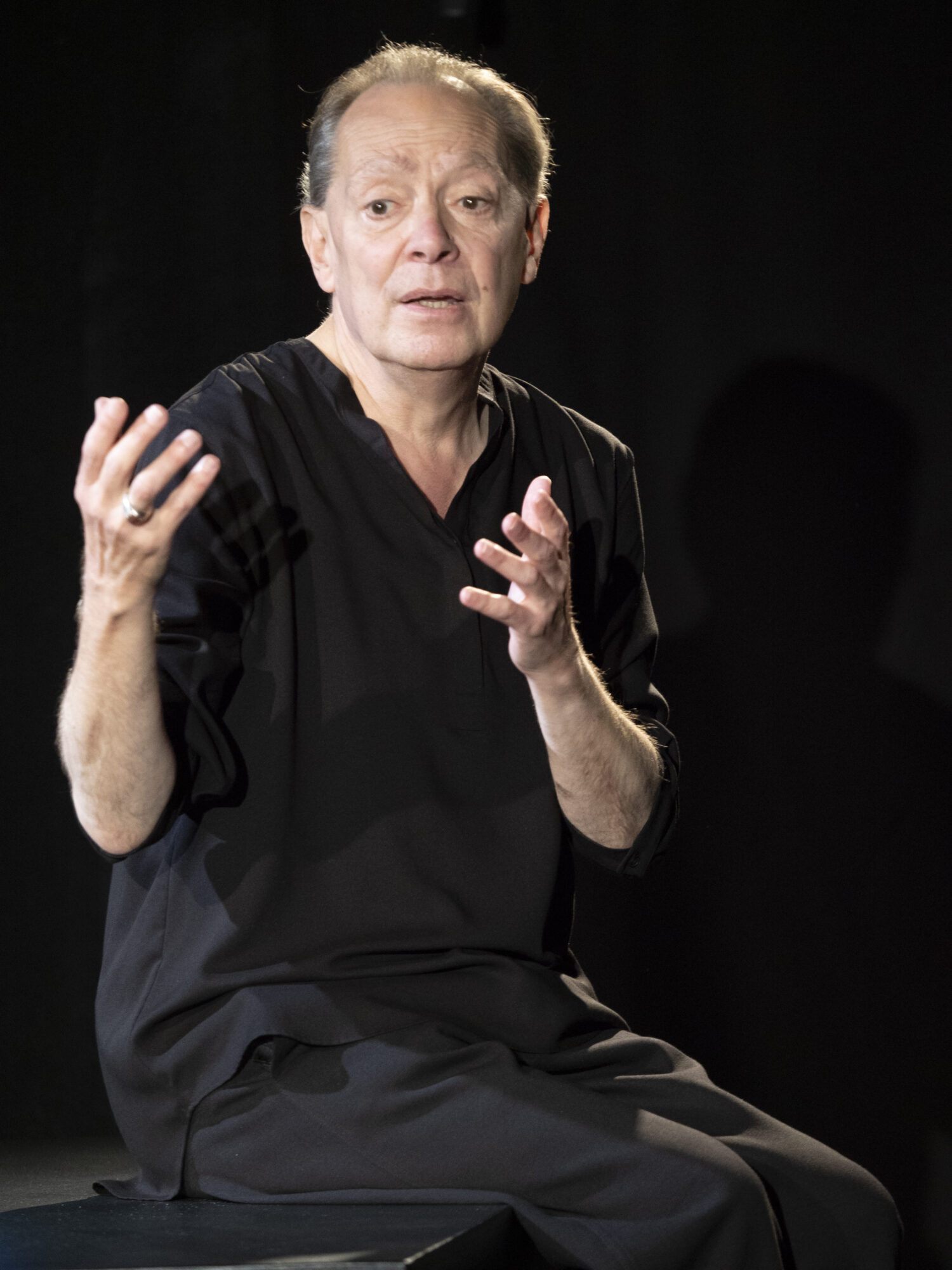

But I was wrong, of course, to be so judgmental, wrong not to give Oliver the benefit of the doubt, because he has built a decades-long career on interrogating his own psyche and making himself vulnerable to exposure and judgment. Now in his early sixties, Oliver’s stage persona is captivatingly paradoxical: he lets the audience into the deepest parts of his memories and self-reflections, while at the same time insisting on his own shyness. He carefully controls every motion and syllable, while avowing that he’s a poor conversationalist.

Photo by Pavel Antonov

Oliver’s pronunciation is legendary. Hilton Als, in an essay about how he learned to stop worrying and love the man, describes his voice as a “stately and sonorous bass that made him sound like a mannered stage actor in an early talking picture, enunciating so carefully you just wanted the words to stop.” To me, he sounds like a demonstrative teacher of elocution lessons. The English letter “r” changes the pronunciation of any vowel that proceeds it (it’s true, try it), and I really love the way Oliver says “a-r” words, as if he’s yawning in the middle: heart, arm, carve, Harvey. You could almost see his tonsils when he talked about the month of March. And he’s an extremely gestural performer. His every finger is a co-star.

Oliver populates the stage with figures from his memories and fantasies. The Mayor of 10th Street Joe Meeks (not to be confused with Joe Meek, the inventor of space rock [it’s true, look it up]), a thief and prostitute so regal Oliver dubs her Queen of the Underworld, a devoted following of cockroaches. They come alive against the gentle set of black boxes which only gingerly suggest brownstones and stoops. And it bears pointing out that Oliver is not alone on stage. There is a small band made up of composer Paul Carbonara on guitar, Samuel Quiggins on cello and Yonatan Gutfield on piano. They provide mood music and punctuational sound effects, and follow Oliver’s every movement with rapt attention, as if to model for the audience how we ought to behave.

Photo by Pavel Antonov

The show description was, in any case, not entirely accurate. It suggests that Victor Greco was homeless for the duration of their twenty-year friendship when in fact, the two men met as neighbors. They were unlikely friends to be sure, Oliver a fey homosexual writer and theatre artist, Victor a muscle-bound lothario. Oliver drank red wine and had a cat, Nefer. Victor drank straight vodka and had a German shepherd, Bull, who Oliver remembers as “a very sexy and passionate dog.” It was only later, after Victor lost his job, then his apartment, then his squat (and Bull, my heart breaks for them both) that he became “a mentally ill homeless man.” And frankly, mentally ill may be a stretch there. If Victor had had an address, he may have just been labeled eccentric.

But actually, they weren’t so different, these two fixtures of East 10th Street, watching the neighborhood’s adventures from their stoop, each drinking out of his own bottle. And Victor, not to be outdone, was a writer himself. Maybe not professionally, but he wrote poetry and fiction on scraps of found paper. He left these texts as notes for Oliver, who incorporates them into the show through voice-over. He quotes work, in particular, a bilingual poem: “La lune est brille/Le ciel est noir/What is that creature/At your door?” The poem was written, he tells us, with two large cartoonish eyes drawn into the “oo” of “door.”

Only some of Victor’s work is quoted by Oliver, more is displayed in a touching exhibit in the theater lobby. It reminded me distinctly of two artists whom I love very much. The first is Ivan Blatný, a Czech poet who tried to escape the communist regime and ended up was committed to a psychiatric hospital in England where he composed fragmented, multilingual verses on whatever bits of paper he could find. A very clever nurse, Frances Meacham, took him and his work seriously and arranged for it to be transmitted to a prominent exile publishing house; it’s thanks to Meacham that Blatný’s singular late works survived, and world literature is the richer for it. The second is Daniel Johnston. Oliver’s play begins, “My friend Victor Greco died in February.” The singer-songwriter and illustrator Daniel Johnston died just last September. I can’t say he was my friend, but I will say his idiosyncratic music, at once raw and catchy, made me feel less alone. Johnston struggled with mental health throughout his life, and some say that his productivity had an inverse relationship to his stability. His death at age 58 of a heart attack was, in some ways, a blessing. It could have been much worse for him. He could have ended up like Ivan Blatný or Victor Greco.

Some artists know how to market themselves and make a career of it. Daniel Johnston famously recorded his own EPs at home on cassette and, not having a tape recorder with duplicating capacities, re-recorded the entire album every time he wanted to make a copy. Other artists’ work comes to us via a benevolent intervention. Sometimes we label these people “outsider artists,” but that’s a term that privileges art institutions – schools, galleries, auction houses – over artists themselves. I could listen to Edgar Oliver tell stories for hours, and thanks to his status on the downtown stage, I can. This particular story, far from being exploitative, introduced me to the work of another great artist: the poet and illustrator Victor Greco.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Abigail Weil.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.