Pistol Dueling in the Early United States as Presented on the Broadway Stage

Two men face off in Weehawken, NJ just before dawn. They hold muzzle-loaded flintlock pistols, primitive firearms by today’s standard. The moment determining life or death will be that instant that triggers are pulled. Once that mechanism is engaged, flint will strike steel, creating a spark that then ignites powder, which in turn propels a lead ball towards their opponent. This lethal action provides some sense of justice over an insult and satisfies the honor of both combatants.

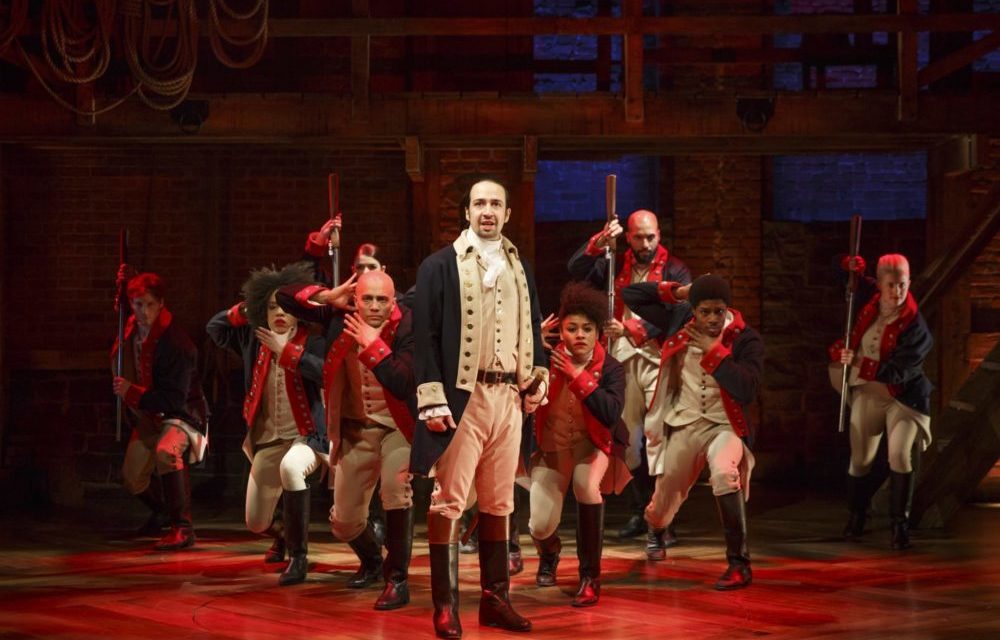

The field, in reality, is a revolving platform at Broadway’s Richard Rodgers Theatre. The play, of course, is Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, a musical inspired by Ron Chernow’s biography of American founding father Alexander Hamilton. The above description can be one of any of the three duels in the play. While each one takes place between different characters in different contexts, all follow the rituals of dueling prevalent in the time period in which the play is set.

Pistol duels take center stage in the play, just as they did in the life of the man himself. Their weaving into the dramaturgical structure of the musical is well worth close examination. No other popular musical has so effectively incorporated dueling and its traditions into its narrative, choreography, and musical composition.

Each of the three duels not only raises the stakes but also builds upon the exposition of the finer points of the code duello from the duel preceding it. Incorporating the exposition of these traditions, with reprising musical motifs accompanying each duel, heightens the action and isolates the experience of that split-second trigger pull into high drama. Taken together, the dueling sequences form a case study in effective dramaturgy for physical conflict (what I’ve come to call fightaturgy).

What makes these duels so compelling, given that the actual act of a character pulling a trigger is incredibly brief? This is a worthwhile question, at a time when gunfire is so prevalent in mass media entertainments that it is often robbed of its dramatic power. In Hamilton, it is the lead-up to and integration of the rituals of dueling that raise the stakes and tensions leading up to each pull of the trigger, and how that trigger pull plays upon the audience’s experience.

Dueling, while frowned upon by the authorities and illegal in most states, was a fact of life during this period of American history. This would continue to be the case for quite some time, especially in the South. The etiquette of entering, or more importantly, avoiding, a duel, was well established. Manuals on dueling etiquette had been in popular circulation in the English language since the Renaissance. In fact, one of the first, Vincento Saviolo, His Practise [1595] is repeatedly referenced in Shakespeare’s Romeo & Juliet. The historical figures that the characters are based on would have been well aware of the intricacies of the ritual.

What follows is an examination of the narrative structure of each duel.

Duel #1: John Laurens & Charles Lee, with Hamilton & Burr as Seconds

Act One introduces the practice, with the procedures laid out in “Ten Duel Commandments.” It is between Hamilton’s best friend, John Laurens, and General Lee, with Hamilton and Burr as seconds. The challenge leading to this duel has been agreed to by Hamilton and Laurens in “Stay Alive,” the song immediately preceding the duel, in which Lee slanders George Washington. Lauren’s line, “Strong words from Lee, someone oughta hold him to it” imply that Lee will be made to answer for his statements and that a challenge will be forthcoming.

That challenge is the first code of the “Ten Duel Commandments.” The song is fairly faithful to dueling codes of the period – the need for both seconds and plausible deniability on the part of participants, as well as multiple opportunities for reconciliation preceding the firing of shots. These opportunities arise first at the moment of potential challenge; second, via negotiation between seconds; and last, once more in person at the dueling ground. Through the song lyric – “Most disputes die and no one shoots” – sung at both the first and last duels of the play, we learn that the moment of aiming and firing at another man is both avoidable and unusual.

In the Broadway production, the performers face each other on a rotating platform in a beat imbued with not just the “moment of adrenaline” of the shot itself, but of an entire formal ritual that may have taken weeks, designed to satisfy honor without leading to bloodshed, and if bloodshed proves necessary, minimize the damage.

The first duel does not lead to a fatality, yet it is not without personal and professional consequences for the protagonist. Washington, his mentor and father figure, has strong feelings against dueling, and Hamilton has let him down by taking part in this one.

This duel provides excitement and conflict and articulation of character while educating the audience in the code duello and setting the structure for the armed conflicts that arise in Act II.

Duel #2: Philip Hamilton & George Eacker, “Blow Us All Away”

In this Act Two duel, Hamilton’s eldest son challenges George Eacker, a man who disparaged his father’s legacy in public speeches. He finds him at the theatre and demands a public apology, to which Eacker not only refuses but also doubles down on his insults. Thus, a challenge is issued and Philip must prepare for his first duel.

Philip goes to his father for advice on the matter, from whom we learn two things. One: Eacker refuses to negotiate a peace and thus forces the duel to go forward; two, there exists an honorable option to clearly aim one’s pistol at the sky and fire, thus putting an acceptable end to the ritual, should the opponent follow suit. Philip’s reservations about exposing himself to harm by “throwing away his shot,” as it were, are met with an assurance that no man of honor would take deadly aim in such circumstances. Alexander even goes so far as to lend Philip his guns for use in this duel. Powerful symbolism is being put into place here, as those same guns will be used on the same dueling ground some years later by Alexander himself.

The option of firing in the air (or into the ground, which might have been truer to history but would not be as dynamic an action on stage) is not mentioned in “Ten Duel Commandments” – perhaps because this option is a finer point of the ritual; perhaps because it would not have been a viable option for either Laurens or Lee in that duel; or perhaps because its introduction at this duel allows greater context for that particular piece of exposition. As is, the addition of that variable introduces elements of hope and mercy into a ritual otherwise focused on mortal combat.

Philip attempts a negotiated peace on the dueling ground itself, which Eacker rebukes out of hand. Stakes are raised as the final attempt to end the dispute without firing has failed. The duel itself commences with similar choreography to the first and a reprise of the dueling motif. Philip, after clearly aiming at the sky, receives a mortal wound.

Violence has consequences, and the fallout of this duel is heavy. The audience witnesses Philip’s dying words to his father, telling him that he did exactly as he was told to satisfy honor without bloodshed, and Hamilton, devastated, retreats from public life.

Duel #3: Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr

Here we have a dramatization of the most well-known duel in American history. By this time the audience is well versed in the rituals leading up to duels, and the options available to combatants. These include the initial challenge itself, attempted reconciliation via designated representatives, selection of the time and place, placing a physician on retainer, etc. This knowledge is essential in order to focus on the escalation of tensions between the two main characters coming to their inevitable conclusion.

The challenge itself takes an entire song (“Your Obedient Servant,”) in which Burr’s demand for an apology is met with escalating animosity from Hamilton. Burr holds Hamilton responsible for his loss in the election of 1800, as well as Burr’s previous political failures, singing: “I look back on where I failed / and in every place I checked / the only common thread has been your disrespect.” Hamilton counters with an assertion that he has only ever spoken the truth regarding Burr and that he stands by his words.

The audience is well aware by now that strong words could either usher in bullets flying or be mediated to some resolution that ends the dispute. Neither character will enter a duel lightly, but then, they leave each other little choice.

“The World Was Wide Enough,” the song in which the duel actually takes place, begins by building on the musical structure of “Ten Duel Commandments.” As the audience has already learned the structure of the ritual, the ten commandments of the duel are replaced with “there are ten things you need to know,” describing the actions taken from Burr’s perspective before shots are fired. For example, Lee’s instructional verse of “duel before the sun is in the sky” in Act 1 is replaced with Burr’s very specific “we rowed across the Hudson at dawn.”

Hamilton and Burr, the seconds in the first duel, are now the combatants. The audience is offered glimpses into their minds and actions; Burr deciding that there is no other recourse if he hopes to reclaim his reputation, Hamilton preparing for the moment of decision, as well as glimpses into their long history with each other (i.e. “Burr, my first friend, my enemy.”) Burr observes that Hamilton intends to fire upon him rather than into the air; he notes that Alexander wears glasses to improve his aim, makes close examination of the terrain, as well as methodical manipulation and testing of the firearm itself. This becomes the justification for his choice to fire directly at Hamilton, whereas for Hamilton we are allowed a frozen moment in time where he reflects at length upon his life and choices. The audience relives Hamilton’s life and loves in his dying moments, and the rest is aftermath.

When Hamilton raises his pistol to the sky, signaling an attempt to end the affair without bloodshed, Burr is surprised. Committed already to firing in earnest, Burr deals Hamilton a fatal shot. Though the audience presumably knows from the start that this moment was coming, the weight behind one great man’s death at the hand of another’s strikes them full force because of the dramatic and musical structures that have been building to this point.

Who Tells Your Story

The musical, of course, condenses and takes liberties with historians’ understanding of the matter. Everything from potential misinterpretation of Hamilton’s actions to the specialized trigger mechanisms in Hamilton’s pistols are glossed over. Miranda himself gives a very nuanced (and comedic) telling of the story in Comedy Central’s Drunk History. That said, Miranda more than does justice to his source material.

The construction of the storyline around both the duels themselves, the events that cause them, and their consequences, are a master class in effective and dramaturgically sound stage violence.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Meron Langsner.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.