An emerging sidelight at the annual Prithvi Theatre Festival is its selection of fringe offerings that are usually showcased at Prithvi House, a first-floor assembly space in the residential building that overlooks the iconic theatre and café. The curation is often hit-and-miss, as is arguably the case with the main festival, but there are many diamonds in the rough waiting to be unearthed by lay audiences and connoisseurs alike. This year’s fringe threw up two separate lyrical offerings from two upcoming actors turned writers turned directors. Indulging his predilection for poetry, Trinetra Tiwari put up Putai, a series of elegiac vignettes staged in a dialect that was a raw mix of Hindi and Marwadi, with musical interludes to boot. And Ajitesh Gupta presented Jo Dooba So Paar, co-directed with Mohit Agarwal. Two years in the making, it is a musical dastangoi on the life and times of Amir Khusrau. Incidentally, Tiwari and Gupta are flatmates in one of the suburban Andheri’s many aspirational enclaves.

Satire, bite, and politics

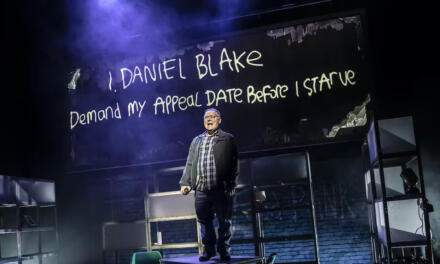

In Putai, Tiwari plays a Rajasthani putaiwala (or ‘house painter’) clad in orange regulation overalls not quite splattered with paint, the labor being entirely simulated. He and his Bihari co-worker (Durgesh Kumar) are de facto narrators of the piece and wear lightly the many couplets at their disposal, handling both the colloquial and literary rhythms of free-flowing verse that never seems out of meter. The play features a tight ensemble of actor-singers, who bring to life episodes from the lives of nameless entities like courtesans in decline or star-crossed lovers or, much more surreally, a lion embarking on a journey to the fictional realm of Tilimistaan. The latter sequence took off from a poem Tiwari had recited at a recent spoken word event organized by Kommune, a storytelling hub.

There is certainly satire and bite and political undercurrents in Putai, but the intensity of verbal expression doesn’t quite allow us to break away to gather our thoughts, which then dissipate and disappear as they came. What remains is a visceral puddle of melancholia and loss, punctuated cursorily by lacings of humor.

Given that we are still early into its run, the scenes in Putai don’t quite move into one another seamlessly, and the play comes across as a loose consortium of scattered ideas, but what is ultimately a powerful unifier is the consistent flavor of tongue employed by the earnest Tiwari.

Spirited performances

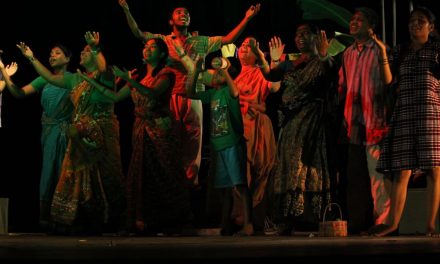

Taking its title from one of Khusrau’s love-poems, Jo Dooba So Paar has been produced by Manav Kaul’s Aranya group, where Gupta cut his teeth as a theatre practitioner for almost a decade — managing productions, acting, and co-directing his first directorial effort, Island — while establishing himself as a regular on the Prithvi circuit. As in Putai, the director-duo of Jo Dooba So Paar have positioned themselves as its raconteurs-in-chief, clad in 19th century white angrakhas typical of dastangos, or exponents of the particular form of oral Islamic storytelling revived by Mahmood Farooqui at the turn of the 21st century. This weekend, the play will be staged at a special dinner for patrons at Jaipur’s luxurious Clarks Amer Hotel, as part of Jairangam, the Jaipur Theatre Festival. It is a piece in which Gupta and Agarwal can give ample display of their singing chops and boyish buoyancy of spirit.

The traditional dastangoi performance dates back to the 13th century. The Persian strand evolved in the 16th century when the 46-volume Hamzanama was first compiled. The manuscript detailed the whimsical exploits of Khusrau’s namesake Amir Hamza, which were narrated as oral dastaans in the court of Akbar (circa 1560). Centuries earlier, Khusrau himself had produced a dastaan-like lyrical masterwork (in the masnavi form) based on the saga of Deval Devi and Khizr Khan (who were contemporary figures).

More recently, his riddle-poems were compiled into a tome, Amir Khusrau: The Man in Riddles, by the late dastango Ankit Chadha, who performed excerpts from the book in the manner of an intrepid dastaan at its book launch.

Others like Syed Sahil Agha have staged their own Dastan-e-Amir Khusrau, and there have been heritage walks in Delhi that end with a musical dastangoi based on the relationship between Khusrau and his pir, Nizamuddin Auliya.

Gupta’s work is yet another chapter in a canon that marries a distinctive theatrical form with the persona of the very individual considered to be a progenitor of the language that is now its mainstay.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.