In June 2017 the eminent New Zealand actor Dame Kate Harcourt celebrated her 90th birthday at Circa Theatre in Wellington, where she was in rehearsals for a new play Destination Beehive. Two years earlier, she was the recipient of a Lifetime Achievement Award from New Zealand Actors Equity. In her lengthy career, Dame Kate has performed in many landmark productions including the premieres of Renée’s Wednesday to Come (1984) and Jean Betts’ Ophelia Thinks Harder (1993). In 1988 she was a founding member of the influential feminist cabaret company Hen’s Teeth. At an age where many have long since retired or moved to a rest home, Dame Kate still performs regularly on stage and screen. As a working professional actor in her 90s, Dame Kate is a positive example of how age does not need to be a barrier for senior actors.

In medical terms, aging is seen as “a process of inevitable decline”[i] whereas acting is often presented in terms of fit, able-bodied young people. Most drama schools carry out out intensive testing during auditions to ensure that potential students have the physical capabilities for the rigors of actor training. What does all of this mean for the professional actor as they face the physical and mental challenges of old age? Due to increasing life expectancies and declining birth rates, New Zealand’s population is rapidly aging, with over 25% of the population predicted to be over the age of 65 by 2051. This has significant implications for healthcare, employment, and social planning. Increasing attention is being paid to the impact of this demographic shift on the theatre internationally. For example, the “Ages and Stages” project in the U.K. brings theatre practitioners into dialogue with social gerontologists, psychologists, and anthropologists, challenging “stereotypes that the capacity for creativity and participation in later life unavoidably and inevitably declines.”[ii] In her book Applied Theatre: Creative Ageing, Sheila McCormick argues that “applied theatre continues to respond to the needs of older adults with the intention to promote creativity, wellbeing and social capital while combating marginalization and social exclusion.”[iii]. McCormick cites studies quantifying the health benefits of older adults participating in the performing arts including improvement in cognitive skills, increased confidence, and ability to make social connections.[iv]The main focus in these studies is on encouraging the participation of the elderly in theatre, and the wellbeing benefits of involvement in creative arts. But how do such studies connect with older professional actors like Kate Harcourt who have spent their lives working in theatre?

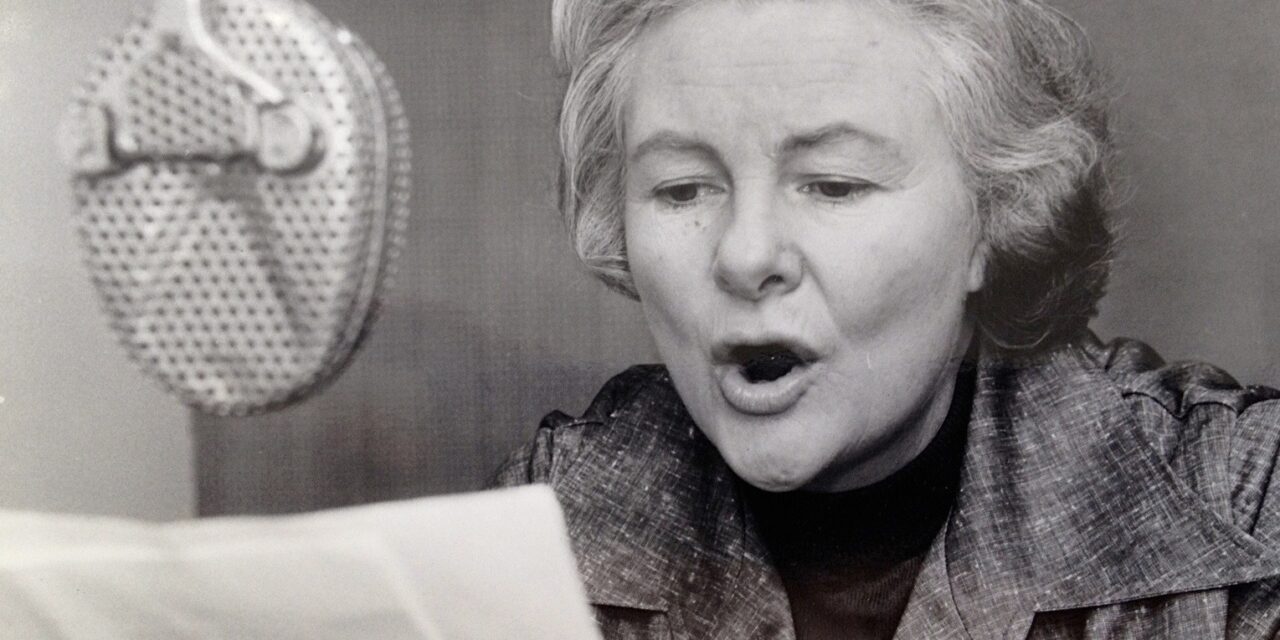

Kate and Miranda Harcourt Listen with Mother., record cover, 1963. Photograph courtesy of Miranda Harcourt.

Catherine (Kate) Fulton was born on the 16th June 1927. She began acting at school, performing in productions such as The Wind in the Willows and The Magic Flute at Woodford House, a private school in Havelock North that was founded in 1894. She was encouraged by a headmistress who was keen on theatre and ended up winning the drama cup. On leaving school she trained as a kindergarten teacher, but a back injury meant she had to leave teaching because she was unable to pick up children. Seeking an alternative career, she moved to Melbourne and completed a three-year opera course at the Conservatorium at Melbourne University, followed by further training at the Joan Cross Opera School in London. When she returned to New Zealand, Kate taught speech and drama at secondary schools. While working at the famously bohemian Wellington coffee lounge Monde Marie in the 1950s, she met her future husband Peter Harcourt who was writing scripts for the revues he produced in partnership with David Tinkham. Kate auditioned for the revues, married Peter, and got her first professional job presenting a popular children’s radio program called Listen with Mother. This was the ideal job for her because it brought together her kindergarten and performance training, requiring her to read stories and sing songs for children. Her seven-year stint on Listen with Mother began a relationship with the Drama Department of Radio New Zealand that continued for several decades. She and Peter were unusual in Wellington at that time in that they were both freelance actors, writers, and broadcasters. Peter joked that they invented the word “freelance”. In order to make a living, Kate had to be entrepreneurial and take on a wide diversity of related jobs, including teaching singing and speech and drama, directing and writing scripts for fashion shows, radio broadcasting, and working as a publicist for Downstage, New Zealand’s first professional theatre (founded in 1964). As acting became a viable profession in the 1960s and 70s, she was cast in roles in theatre, television, radio drama, and film. At Downstage her roles included the maid Bertha in Colin McColl’s acclaimed production of Hedda Gabler (1990) which toured to Edinburgh, London and Sydney.

Dame Kate Harcourt in advertising campaign for online music. Photo courtesy of Miranda Harcourt.

One of Kate’s most significant roles at Downstage was playing Mary in the first production of Renée’s Wednesday to Come in 1984. In its naturalistic depiction of the struggles of women during the 1930s depression era, Wednesday to Come is recognized as one of the most significant plays in the canon of New Zealand drama. Kate played Mary, one of four generations of women in the same rural family dealing with the aftermath of the suicide of the family breadwinner at a forced labor camp. As Mary bakes (real) scones onstage to support the mourners, she exemplifies the play’s feminist themes, illustrating that women’s unpaid domestic work keeps the nation going in times of adversity. The role seemed a natural extension of Kate’s persona in her radio show Listen with Mother – the nurturing, supportive motherly figure. But this was a harder-edged portrait of a pragmatic, resilient, working-class mother. For Kate, it was also a career landmark in portraying a recognizably New Zealand woman:

It was great playing a New Zealander, playing somebody that I knew. I suppose it would have been one of the few (New Zealand roles I played) because most of the plays we did were British, weren’t they? I enjoyed it very much.

When Wednesday to Come was re-mounted at Downstage in 2005, Kate, now 21 years older, played the character of Granna. There is a line in the play where Granna, who shares the name Jeannie with her 13-year-old great-granddaughter, says “I was Jeannie once”. Here Renee makes the point that as we age we lose our identity as individuals and are seen merely as old people. Granna’s line asks that she be recognized as the individual she once was rather than being solely characterized in terms of her age.

Kate Harcourt as the Queen in Ophelia Thinks Harder by Jean Betts, Circa Theatre, 1993. Photograph courtesy of Miranda Harcourt.

Kate’s husband Peter died of cancer in 1995. In 1996, she became Dame Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit (DNZM) for services to theatre. In 1999 she toured widely in Flowers from my Mother’s Garden, a verbatim play about her own life written by her daughter Miranda Harcourt and son-in-law Stuart McKenzie. Now Kate is the matriarch of a celebrity show business family with three generations of actors working concurrently. Miranda Harcourt has been one of New Zealand’s leading actors and directors for several decades, and an internationally renowned acting coach. Kate’s granddaughter Thomasin McKenzie has developed a successful international film career since she received critical accolades for her performance in Debra Granik’s film Leave no Trace in 2018. Leave No Trace was screened in Director’s Fortnight at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival, the same year that the festival featured Miranda’s film The Changeover, co-directed with her husband Stuart McKenzie. In The Changeover, Kate plays the benign witch Winter Carlisle. Thomasin has gone on to play roles including Elsa in Jojo Rabbit (directed by Taika Waititi), Eloise in Last Night in Soho (directed by Edgar Wright), and Mary in True History of the Kelly Gang (directed by Justin Kurzel). She is currently filming an untitled project directed by M. Night Shyalaman. Thomasin’s younger sister Davida McKenzie travelled to London earlier this year to act in Silent Night, a film starring Keira Knightley and directed by Camille Griffin.

In preparation for this article, I interviewed Dame Kate Harcourt at her home in Wellington, which she shares with her extended family. I asked about her training as a singer and actor, and which directors had been most influential in her career. She highlighted the ‘inspired’ directing of David Tinkham, Peter Harcourt’s revue collaborator who taught her the importance of timing, and Davina Whitehouse, who directed her in Radio Drama as well as performing with her in many productions. She credits Davina with teaching her the nuances of timing, vocal delivery, and how to ‘get under the skin’ of a character. In creating a character she highlights most of all the importance of the imagination, which she credits as one of the most important things for an actor.

She also discussed the importance of nerves in her process:

I get nervous on stage, I think you have to. Not shatteringly so, but enough to be on your guard you know, to be on your toes. I think if you’re not properly nervous you don’t give a performance. I just keep going. But it makes you more alert I think, more aware. But to say you’re not nervous appearing in public would be nuts. I’ve got less nervous as the years have gone by, but creative nerves I think you’d call it. Heightened awareness.

I was interested in whether Kate encountered any barriers or obstacles in being an older actor. I asked how she coped with the demands of night shoots for her role in The Changeover. Her reply illustrates her pragmatism and independence: “I just sleep in the next morning”. I’m aware that it’s the most awful cliche to ask an actor how they remember all those lines, but I felt, given Kate’s advanced years, that this was a reasonable question. She replied:

I used to have terrible trouble with lines, but I’m having less trouble the older I get. I’ve got something coming up next week, I’ve had to learn a song and learn the lines. Just repetition. I’ve been learning lines my entire life and forgetting them. I had a bit of trouble with those lines in Destination Beehive. The pianist had the script with him. He could prompt me if I went wrong. So, no, it’s always been a difficulty.

This suggests that the challenges Kate faces as an older actor are a little different from those she has faced throughout her entire career. She now walks with a pronounced stoop and walking stick. However, in her 20s she had to give up kindergarten teaching because of this same back injury, so she has successfully managed this condition throughout her lifetime as a professional actor. Research by sports scientists suggests that with exercise, “physical function in later life is amenable to improvement”[v]. I suggest that Kate Harcourt’s wellbeing in her 90s is linked to her continuing exercise of mind, body, and imagination through her work as an actor, and her refusal to be defined by her age.

Two of Kate’s performances from her 90th year illustrate the range of her influence: these were in the 2017 World of Wearable Arts (WOW), a spectacular theatricalized fashion show which plays to audiences of approximately 60,000 each year, and in a revival of the classic feminist cabaret Hen’s Teeth at Circa Theatre’s Women’s Theatre Festival in March 2017. In the WOW show, directed by Kip Chapman, the choreographed fashion sequences were united by a narrative depicting the life of a fictional woman, Lucy, whose life is vibrant and colorful as a child but as she grows into middle age, becomes drab and conventional. Through the agency of the wearable art show, she recovers her sense of awe and wonder and transforms into a stylish creative person. Actors of different ages play Lucy throughout the show, and her oldest manifestation was played by Kate Harcourt.

As an audience member, I experienced Kate’s performance as one of the most effective theatrical moments in a show full of coups de théâtre. A group of dancers in red slips surrounded the mid-life Lucy (Alison Bruce), wearing a somewhat drab dress. All turned with their backs to the audience facing a huge red silk backdrop. From a fold in the curtain emerged a small figure in a sparkling red jacket and red skirt. As the crowd recognized Dame Kate Harcourt, they went wild with cheering and applause. As the older Lucy, Kate counseled her younger self. “Let’s have a look at you,” she said warmly “You only get one life kid, so go out there and grab it.” Kate turned upstage to the dancers and showed them her nails. “Look, see my nails, they’ve got cats on them, aren’t they fun … You can get them too. I can tell you where to go, it’s a place in Cuba Street”. The audience erupted with laughter at this mention of Wellington’s most bohemian inner-city street. “I’ll let you know the address. Come on, hurry up.” Kate vanished into the throng of dancers, they followed her upstage, and as the lights faded, there was another sustained round of applause from the audience. In this brief appearance, Kate presented an empowering image of an older woman – relatable, cheeky, and creative – that was received with immense enthusiasm by the audience.

In stark contrast to the glitz and glamour of WOW, in Hen’s Teeth, produced by Kate JasonSmith, Kate played a curmudgeonly pensioner named Maud Hornby in a sketch originally scripted by herself for the Hen’s Teeth shows in the 1980s. In the sketch, Maud has been recruited for a promotional video for the rest home where she resides. She enters the stage barely mobile on two walking sticks, wearing a neck brace, a hairnet, covered in bandages and safety pins, dressed in a cardigan and fluffy slippers. Maud is a carefully curated compendium of all of the clichés of old age. She protests about the nagging she encounters daily from the staff at the home, then she complains about not being able to see the cue cards because someone’s hidden her glasses. As she begins the prepared spiel extolling the benefits of the home she undermines the promotional hype by adding in her own comments, such as noting that the residents use the chapel to play cards. I saw this sketch in the 1980s and again in 2017, and the impact of the sketch was enhanced by Kate’s advanced years. Clearly, she was more qualified than most to present the reality of aging. As in the WOW show, Kate’s appearance was greeted by applause and cheers from the audience. As Maud, Kate displayed impeccable comic timing, riding the audience responses, gaining belly laughs from the audience on almost every line, thought, or glance. Since she first performed this sketch retirement homes have become one of the fastest-growing industries in New Zealand due to the aging population. This gives the script arguably more immediacy and relevance than in the 1980s. Maud ends by reluctantly endorsing the rest home, as per her script, then adds, “It’s the people that piss you off” which brings the house down.

The glamour and star power of Kate’s brief appearance in the WOW spectacular is a stark contrast to the subversive impact of Maud Hornby’s dark comedy. The WOW performance presented an immensely positive image of old age in a highly creative context, unequivocably suggesting that women can become more independent and creative with age. Viewed together, these performances are playful and subversive, contesting stereotypes by celebrating independent thinking and confidence in old age.

Kate Harcourt and Sophie Hambleton in The Pact, a short film written and directed by Natalie Medlock, 2017. Photograph courtesy of Miranda Harcourt.

In her autobiography Dame Judi Dench offers the tongue in cheek observation “You don’t need to retire as an actor, there are all these parts you can play lying in bed, or in a wheelchair.”[vi] Kate Harcourt has certainly not retired, and her recent roles depict her as anything but passive or disabled. Her activity and agency contests the cliches of the flourishing genre of Grey Cinema. For example, in the 2012 film Quartet, a group of elderly opera singers eke out their last days in a home for retired musicians, overcoming adversity in order to perform the famous quartet from Rigoletto one last time. In contrast, Kate Harcourt does not appear to perceive any sense of adversity in continuing to work as a freelance actor, as she always has. In her nineties, she still considers herself a jobbing actor performing in theatre and short films alongside more high profile celebrity appearances. Most recently she has appeared in the consumer affairs television series Fair Go and has recorded voiceovers for an Electoral Commission radio campaign promoting the 2020 parliamentary election.

While applied theatre for the elderly can bring quantifiable benefits to society, the resilience and energy of older actors like Kate Harcourt provide a positive role model, not only to younger actors, but also to their contemporaries, older people in general. Sports scientists advocate for physical training for older people, promoting what Tulle labels “the reconstructed older adult … strong, trainable, with improved psychological and health status and, ultimately, with greater wellbeing derived from having regained control and independence.”[vii] Kate Harcourt has no need to be “reconstructed” as she already exhibits all of these qualities. Her example shows that it is possible to continue to work into old age, that the cliches and stereotypes of old age are an illusion. Especially in her live theatre performances, her very presence on stage contests the biological notion of age as an inevitable process of decline. In her interview, she spoke passionately about acting techniques including exercising the imagination, timing, energy, pacing, memorization, breath control, alertness, and utilizing creative nerves. Her deployment of this actor training contributes to a sense of vitality which is lacking in many people younger than her. Her recent career achievements demonstrate that not only is she a highly public figure who provides positive inspiration that older people can lead rich fulfilling lives, but also that some form of actor training could be beneficial to many older people, enhancing their enjoyment of life and keeping them active, independent, creative and socially engaged.

[i] Tulle, Emmanuelle. “Acting your age? Sports Science and the ageing body”. Journal of Aging Studies 22, 2008: 340-347, 340.

[ii] Bernard, Miriam, Michelle Rickett, David Amigoni and Lucy Munro. “Ages and Stages: the place of theatre in the lives of older people”. Ageing and Society 35(6), 2015: 1119-1145, 1119.

[iii] McCormick, Sheila. Applied Theatre: Creative Ageing. London: Methuen, 2017, 41.

[iv] McCormick 2017, 43-4.

[v] Tulle 2008, 340.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by David O'Donnell.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.