Strange Fruit

They were pronounced dead on the scene.

Sunday morning, September 15th, 1968, 14-year-old Addie Mae Collins pampered herself in the bathroom of her church. Her and three other young girls, 11-year old Denise McNair, and 14-year-olds Cynthia Wesley and Carole Robertson stared at their black faces in the mirror. They played with their kinky wooly hair, unassuming and unsuspecting of the 19 sticks of dynamite which rested underneath their feet.

September 15th, 1968, on a Sunday morning, the pastor of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama prepared a sermon on love and forgiveness. Unaware of the four members of the Ku Klux Klan who had planted bombs in his church, in preparation to decimate and destroy every black body in sight.

They were pronounced dead on the scene.

A survivor said their bodies flew into the air the way one throws up a rag doll. Barely identifiable; one of the little girls had been decapitated, only recognizable through the Sunday school clothing she had worn that morning; another little girl, found with mortar pierced through her skull.

They were pronounced dead on the scene, 47 years before Dylann Roof would sit in the pews of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina and place bullets into the backs of innocent black bodies. Those four little girls—Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Cynt

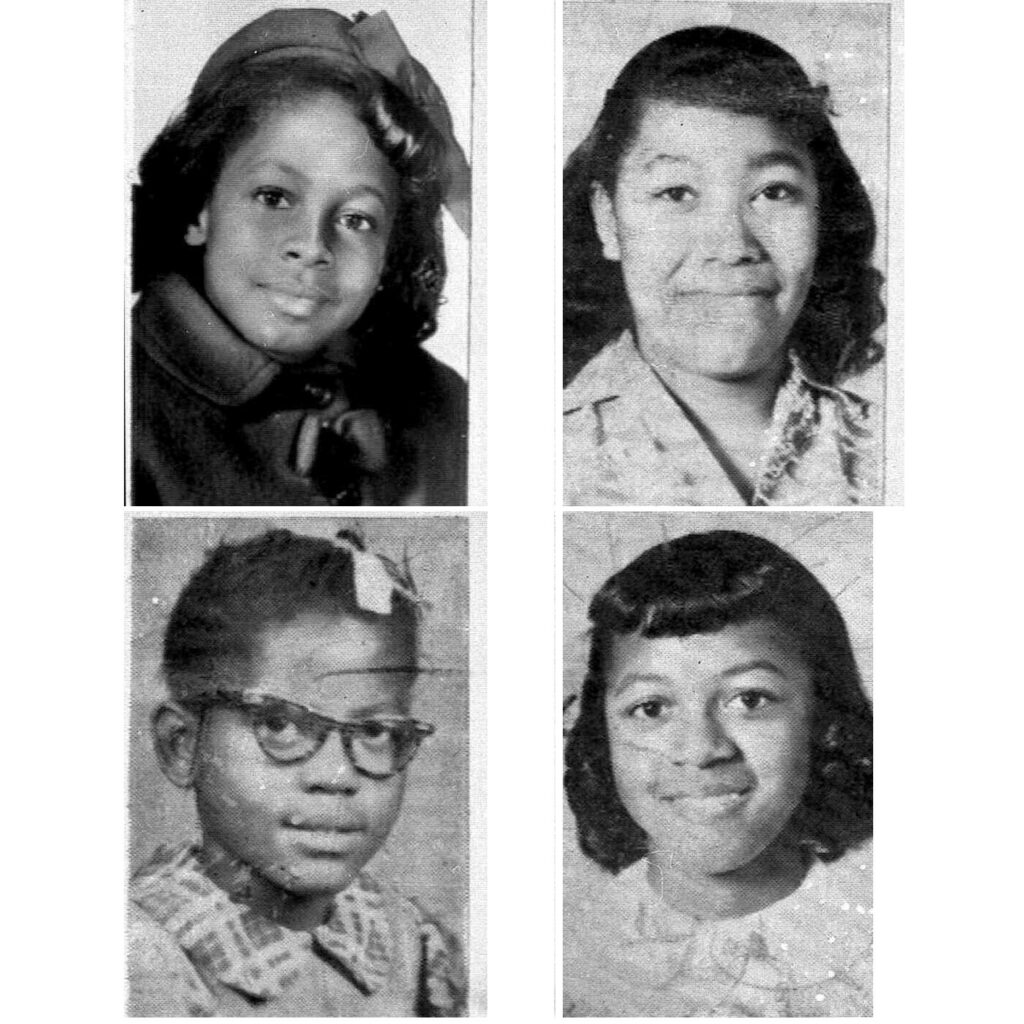

Clockwise from left: Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, Denise McNair, and Addie Mae Collins. Photo credit: AP Photo

hia Wesley, and Carole Robertson, were pronounced dead on the scene.

And the world, for decades, knew nothing about them; simply referring to them as those poor “four little girls.”

Playwright Christina Ham sought to change that.

Ham found herself in Birmingham one day, researching the 16th Street Baptist Church, as she prepared to write the play Four Little Girls: Birmingham 1963 for the SteppingStone Theatre in St. Paul Minnesota.

“[The bombing] was such a pivotal turning point,” she said. “Not just for black people…but for this country in general.”

Ham sought to put Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Cynthia Wesley, and Carole Robertson on a national stage; identifying them by names, and personifying the narratives of those girls whose life stories have become nothing more than a reminder of the pain associated with being black in this country. Ham wanted to know what their hopes were, and if they had any dreams before they died.

“The artistic director wanted the play to put names to the term ‘four little girls,’” she said. “My mom’s family went to the church where they were murdered.”

In her play Four Little Girls, Denise McNair had dreams of becoming a doctor, while Carole Robertson dreamt of the dress she would wear for cotillion; Cynthia Wesley wanted to become a math professor, and Addie Mae Collins wanted to become a basketball player. The play was met with critical acclaim and has since been produced around the country, including a staging by actress Phylicia Rashad at the Kennedy Center, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing.

Ham had succeeded in giving a narrative to the four little girls. But a piece of the puzzle was still missing.

And it took her seven years to find it.

Little Blue Girl

Christina Ham.

Photo courtesy of Christina Ham

Christina Ham received her master’s in playwriting in 1995 from UCLA. Having briefly studied journalism during her undergraduate years, she stated that the skills utilized by investigative reporters had never served her more than it did once she became a playwright.

“I actually feel like the part I hated about journalism, is actually the thing that aided me the most in playwriting,” she said. “Because I think playwriting is all about investigation, so it’s fact gathering, it’s reading, it’s asking questions of the material in of yourself, and then writing the story.”

In the beginning of her career, she would be commissioned for projects which surrounded Black history. But as she began conducting research, she realized there were many stories regarding her own culture that she never learned about. Quickly, she began to re-focus her artistry on retelling the narratives of African-Americans.

This is when she found herself writing Four Little Girls for the SteppingStone Theatre in St. Paul, Minnesota.

“I was able to interview my mom as part of the process of finding out what it was like to be a young black girl in Birmingham at the time, and what were the things she loved doing,” Ham said. “Because those [things] would have been very similar to what was available to the young girls at the time.”

Ham was born and raised in Los Angeles, though her parents are from Alabama and South Carolina, respectively. Growing up in California, Ham knew that her perception of racism and her experiences of discrimination were different for her than for someone who grew up in the South.

“[In L.A.] it’s more subversive,” she said. “A lot of that has to do with the real estate laws in this state. I think once you start to understand that, you start to understand the larger context of how this country continues to perpetrate advantages and disadvantages for people in ways that have long-standing consequences, even to this day.”

In order to fully understand the black experience in America, Ham began to research the experiences of the black people who lived in the South and find the lost stories to put on center stage.

“The reality of what [their] history was, I did not know,” she said. “[But] they were real people, and to leave that from their narrative, I would not be doing my job as a writer.”

Another influence for Ham was the work of Nina Simone, who was also deeply impacted by the 16th Street Bombings, and served as inspiration and namesake for Ham’s latest play, Nina Simone: Four Women.

“[Simone] could never go back to the way she was creating as an artist,” Ham stated. “It was important for her to really tell the stories of black people during the Civil Rights Movement through music, that she herself created and not to be covering songs by white artists anymore…it was really important for her to provide the soundtrack for the Civil Rights Movement and [for] those people who were on the ground fighting for those rights.”

Though Simone’s song Four Women was released two years before the bombing, on her album Wild Is The Wind, the meaning of the song changed the more Simone involved herself with the black liberation movement at that time.

Simone’s song depicts four people, each representing an archetype of the African-American woman. The first, Aunt Sarah, represents enslavement and possesses the traits of resilience, bearing the welted scars of slavery on her back. The second woman is Saffronia, who is of mixed race, depicted as living between two different worlds, though she is still oppressed; her father, a rich white man and she, the product of him sexually assaulting her mother one night. The third woman is a prostitute named Sweet Thing, who finds acceptance in the white and black world, as she pleases both with her sexuality and submission. The last, is a tired woman, weighted down by the generations of marginalization and oppression endured because of the color of her skin. She proclaims she is “awfully bitter these days / ‘cause my parents were slaves.” After a dramatic pause, Simone screams out the name of the last woman—her name is Peaches.

“She considered herself to be one of the four women,” Ham said. “I feel like I am all of those women, I think pretty much all black women go between all of those women, depending on what day of the week it is.”

But Ham didn’t intend for her play Four Women to be a musical, even though Simone’s protest songs are used to narrate the story.

Production set for Nina Simone: Four Women, which recreates the interior of the 16th Street Baptist Church.

Photo Credit: Ron Cogswell

“I wasn’t interested in doing a biopic on the stage of one our premier black artists,” she said. “It was to be honest and tell the truth about who these women [were], and what these conversations were, and how we were casted [aside] within the Civil Rights Movement.”

Often subjugated to much controversy in her life, Simone always found ways to be heard. Even if it meant almost losing her career. Black women, like Simone, are, even today, left out of the conversation surrounding the movement of black liberation. Critics found Simone too radical regarding her thoughts on civil rights and feminism. Her song Four Women was even cast aside by the black community, who felt that her exposing the community’s issues with colorism to white audiences was inappropriate.

“Black women were not marching with their men and Martin Luther King on the street,” Ham said. “They were on a separate street.”

Ham’s play Four Women also does not focus on the wider scope of Simone’s life–such as mentioning the singer’s mental health struggles or her relationship with her late husband. Instead, the play offers a glimpse at a moment in time, in which the singer’s life was embattled with the pain and heartache of seeing African-Americans being beaten and dragged in the streets, while also being censored and scorned when she, a woman, tried to speak out.

“Bob Dylan wasn’t being censored for his songs,” Ham said. “[The play] is really trying to put all that complex history into context.”

Ham also recalls the cathartic feelings felt by both her and audiences after seeing Four Women, as black women, especially, were finally able to see themselves represented on stage, with a story that finally spoke, not only about the racism and sexism they face but also about the colorism and the classism which impacts them as well.

“These conversations in the black community are hard to come by. At least [the] audiences that I’ve experienced [the play] with, have seen it as a type of healing,” she said.

Four Women is currently being staged around the U.S. and abroad, including at the Northlight Theatre in Chicago, the Seattle Repertory Theatre in Seattle, Washington, and the Market Theatre in Johannesburg, South Africa. Each production has a different director bringing forth a new perspective on the story, focusing on educating audiences around the world.

“There are too many people that don’t understand the history of the country we live in,” Ham said. “And I am still learning, but I am willing to lean, and it’s going to be a lifetime journey.”

Though, as she continues to use theatre as a tool for education, she realizes theater’s accessibility still removes groups of people, mostly due to the monetary restraints theatre places on those who cannot afford to go.

“I just started writing for television and nearly hundreds of millions of people saw my episode,” she said. “In a way that even [with] the most sold out house in the theatre, most people will still [never] know these stories.”

Now, Ham has decided to take advantage of the large platform television has provided her, and has even begun thinking of her next big project–and it doesn’t stray too far from the historical realism genre she currently finds herself in. Her next project will be a classic L.A. Noire story, about a black woman detective working during the 1960s Watts riots.

“It’s about reclaiming where the black woman is in our historical narrative,” Ham said. “And making sure that people know about it.”

Now ten years after the premiere of Four Little Girls at SteppingStone, Ham has found herself connecting Four Little Girls and Four Women, which together, not only tell the story of what was once a moment in time but rather, a story which now embodies generations of black women in America. The two pieces are now often performed together. Because as time would have told, those four little girls would have grown up to be four women, and without playwrights like Ham, the narratives of their lives would have been erased throughout the course of history.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Dominic-Madori Davis.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.