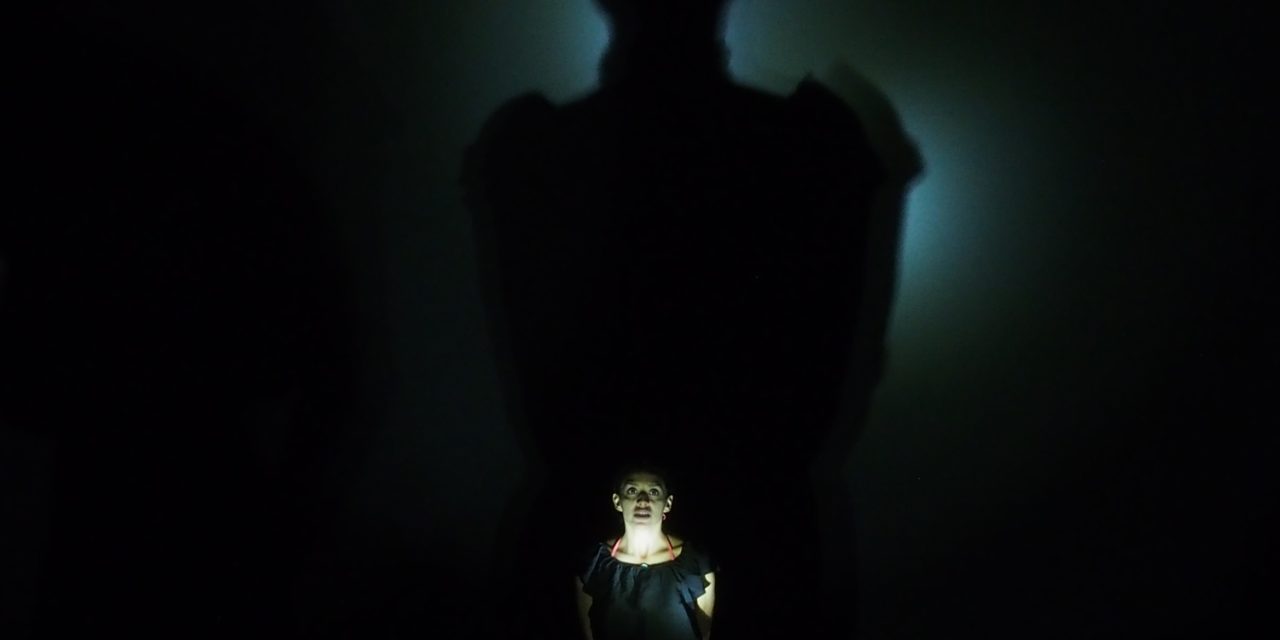

Chekhov’s Three Sisters is distilled into vibration and iteration in The Hummm, a radical adaptation by a collective of artists led by director Kai Chieh Tu at Dixon Place, NYC.

The soundscapes of Chekhov’s plays have presented particular challenges since Stanislavsky staged The Seagull at the Moscow Art Theatre in 1898. The playwright and director famously quarreled over whether or not the play was a comedy, and over Stanislavsky’s insistence on overwhelming the play with “realistic” sound effects where Chekhov had asked for simplicity. In his production notebooks, Stanislavsky, who later admitted that the play went over his head, describes the opening scene in his production notebooks:

“distant sounds of a drunkard’s song; distant howling of a dog; the croaking of frogs, the cry of a corncrake, the slow tolling of a distant church-bell. All this helps the audience to get the feel of the sad and monotonous life of the characters. Flashes of lightning, faint rumbling of thunder in the distance…Yakov knocks, hammering in a nail…he busies himself on the stage, humming a tune.”

Chekhov was so distressed by the literal, lugubrious, and flat out wrong atmosphere this approach produced that he fell seriously ill and became determined to abandon the theater forever, convinced that a second such failure would kill him. Fortunately, his determination wavered, and Chekhov went on to write plays that occasionally included confounding, otherworldly stage directions such as the one that comes in Act Two of The Cherry Orchard while the Ranyevskaya circle sits pensively on an outing in the countryside. Suddenly we hear “the sound of a harp string breaking,” a sound that unsettles the entire dramatic framework, that (to borrow the language of cinema) exists in an unnerving place between the diegetic and extra-diegetic, and that invites both Chekhov’s characters and spectators to question the coherence and permanence of their worlds as they appear.

In Chekhov’s purest drama of wasted human potential the titular three sisters Olga, Masha, and Irina Prozorov are uneventfully withering on the vine out in the provinces until their brother brings home the nouveau riche Natasha as a bride and the captivating Lieutenant Colonel Vershinin comes to town, recalling them to a time when it seemed the world wanted them. As it happens, Vershinin really does want Masha, and she him. Despite their unhappy, but inescapable marriages to other people, the pair embark upon a love affair that until the play’s end mainly manifests itself dramatically through sound. By Act Three, Masha and Vershinin are so attuned to one another that they have worked out their own frequency, communicating across crowded rooms using apparently meaningless, casual snatches of song. “I’m in the strangest mood today,” Vershinin says, “I feel an urge to live, to do something wild!” A playful, but pregnant duet follows:

MASHA: Tram-tam-tam

VERSHININ: Tram-tam

MASHA: Tra-ra-ra?

VERSHININ: Tra-ta-ta. (Laughs)

Seldom able to say all that they mean, Chekhov’s characters find themselves very much at home in The Hummm, which, as the title suggests, mostly dispenses with words as the primary site of meaning-making, and focuses on the wavelength as the most basic building block of human connection. Chekhov’s plays are often likened to music, with one character introducing a leitmotif that resurfaces in the form of a similar existential complaint voiced by other characters later on. His complete oeuvre can be said to work the same way, and the Hummm company exploits this by incorporating text from some of Chekhov’s short stories in addition to original Chekhovian-sounding language, sometimes ripped from the headlines and juxtaposed with the source material in apt and surprising ways. Solyony opines that “When a man talks philosophy you get philosophy, or at least sophistry, but when a woman talks philosophy, or two women, all you get is wee, wee, wee, all the way home.” Then we hear Masha identified as a “nasty woman,” a phrase that will for the foreseeable future be associated with the characteristically vile and churlish epithet flung by Donald Trump at Hillary Clinton during the third 2016 presidential debate. In a quotation from Chekhov’s 1899 “The Darling,” which follows the story of a woman who allows her thoughts to be dictated by the dominant men in her life, a man hisses at his lover that she ought “not to talk about what [she doesn’t] understand.” In The Hummm this quotation is followed by a quotation of a quotation: Melania Trump’s plagiarized 2016 Republican National Convention speech. All speech is inadequate, but some speeches are less adequate than others.

But The Hummm mostly treats language as pretext, flooding the theater with sonorous suggestions. Music that evokes by turns the recklessness of youthful desire and the resignation of youth grown old too soon prompts wild dances that spill into the audience (we enter the theater to find our seats equipped with a note reading “BLOW ME” along with a balloon that later becomes a prop), but these explosions never quite overwhelm the sense of melancholy. Painted faces are later effaced. We hear the chugging of a Moscow-bound train. In this version, the sisters do finally get to the chimerical Moscow of their collective imagination, but their final monologues are delivered with their heads buried in metal buckets, their professions of faith in the value of work and suffering reduced to thoughts echoing inside their own heads. With the company’s timely interpolations regarding the ascent of Trump, the decline of truth, and the questionable efficacy of a woman making sound of any kind, Richard Gilman’s observation about Chekhov’s plays still applies. Their general atmosphere of defeat bespeaks a recognition, Gilman writes, “if seldom a full acquiescence in it, on the part of the characters who with one intensity or another have passed beyond illusion: love will not save me, work will not ennoble me, the future won’t rescue the present.”

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Jessica Rizzo.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.