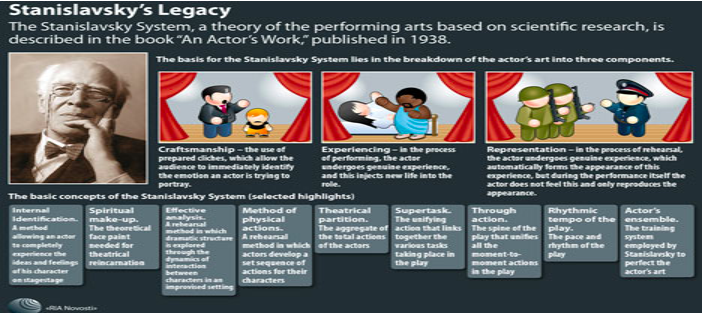

Born 150 years ago, Stanislavsky created the method that revolutionized 20th-century acting and brought it to the American stage.

Source: RIA Novosti

Russian actor and director Konstantin Stanislavsky, who was born 150 years ago today, toured the United States with his actors in 1923 to great acclaim. Stanislavsky and his students trained Americans, like Lee Strasberg and Stella Adler, who would go on and teach their interpretation of “the method” to generations of American actors.

Stanislavsky was encouraged to write his autobiography, which was swiftly translated, rather roughly, into English. The dedication to his book My Life in Art (1924) reads: “I dedicate this book in gratitude to hospitable America as a token and a remembrance from the Moscow Art Theatre which took so kindly to her heart.”

The early 1920s were a difficult time for Stanislavsky. His son was suffering from tuberculosis and while Stanislavsky was a giant on the stage, he still badly needed foreign currency to treat his son in a European sanitarium, according to historians. The U.S. trip assisted him in that effort.

The Toast Of Moscow—And The World

Actors all over the world, and especially in the United States, are still inspired and nourished by the great theatrical pioneer, one of the most internationally influential figures ever to have lived in Moscow.

His handbook An Actor Prepares”, published in 1936 two years before he died, is still a standard text for drama students around the world. His famous “method”, promoting the naturalistic style of acting that we take for granted today, broke away from the stilted traditions of 19th-century theatre. Moscow was Stanislavsky’s birthplace, lifelong home and final resting place. It was also the venue for his far-reaching discussions and experiments.

On June 22, 1897, Stanislavsky had an all-night meeting with Vladimir Nemirovich-Danchenko, which led to the founding of the Moscow Art Theatre. The old Slavyansky Bazaar restaurant on Nikolskaya Ulitsa, where they met at 2 p.m., no longer exists; but the theater that eventually grew out of that famous dinner is still going strong a few streets away on Kamergersky Pereulok.

A year later, on June 14, 1898, the company met for their first rehearsal in the nearby town of Pushkino. Stanislavsky’s opening speech urged the new team to dedicate their lives to creating “the first rational, moral and accessible theater.” Here are some of the other Moscow sights associated with the great director and his work.

Gold And Silver Threads

Source: RIA Novosti

Among the merchant families that facilitated the great creative boom in 19th-century Russia were the Alexeyevs, textile magnates specializing in the manufacture of gold and silver thread. The house where Konstantin Alexeyev (who later became “Stanislavsky”) was born in 1863 is a large, neoclassical mansion. It is on a street that is now named after Alexander Solzhenitsyn, near Taganka, lined with the elegant houses of other wealthy merchant families. Stanislavsky’s cousin Nikolai Alexeyev became mayor of Moscow in 1885.

On the next street, predictably renamed Ulitsa Stanislavskogo, the magnificent, curving redbrick Alexeyev family factory has been transformed into offices. The area is well worth exploring, not least for the unusually sensitive and tasteful modern architecture.

The main factory dates from 1912 and now has a great café on one side of the open-plan ground floor. The lampshades in the café, designed to look like spools of silver thread, are a subtle reminder of the factory’s original purpose.

Source: RIA Novosti

One of the offices on the upper floor has a giant transparent version of a famous photo of the read-through of The Seagull across its plate glass window. Stanislavsky sits next to the playwright, Anton Chekhov, surrounded by the other members of the Moscow Art Theatre. In a courtyard behind the factory, one of the older, more ornate buildings was converted back into a studio theatre in 2008.

Stanislavsky worked here in the 1880s and founded his first theater as part of the Society of Literature and Art. According to the studio’s new director, Sergei Zhenovach, “Stanislavsky created his theater here to stop the workers from drinking in their spare time.”

Fate Has Been Kind To Me

Source: RIA Novosti

Stanislavsky did not forget his privileged upbringing. “Fate has been kind to me,” he wrote in his autobiography, My Life in Art: “I began my life at a time when there was considerable animation in the spheres of art, science, and aesthetics. In Moscow, this was due to a great degree to young merchants who were interested not only in their businesses but also in art.” The entrepreneur Savva Morozov donated 500,000 roubles to set up the Moscow Art Theatre.

Gold And Silver Threads

Source: RIA Novosti

The Alexeyev family did not approve of professional acting as a vocation for their son, leading to Stanislavsky’s name change in 1884, but they nonetheless fostered his love of theater. He grew up amid a flourishing tradition of amateur dramatics. The family estate at Lyubimovka, with its theater barn, is sadly derelict; but you can see a reconstruction, together with an exhibition about the young Stanislavsky, on the top floor of the house-museum on Leontyevsky Pereulok.

Not In A Grammar School

Source: RIA Novosti

The Maly Theatre – the smaller yellowish building next to the Bolshoi – played an important role in Stanislavsky’s developing ideas. In his memoirs, he wrote: “The Maly Theatre defined our spiritual life… I can safely say that I have received my education not in a grammar school but in the Maly Theatre.” At the same time, he rebelled against the mimicry and melodrama of theatrical convention, leaving the Moscow Theatre School in a matter of weeks. The opera singer Fyodor Chaliapin was another important influence. Performing at the Private Opera, funded by businessman Savva Mamontov, Chaliapin sang with great emotional power and verisimilitude. Stanislavsky later wrote that many elements of his method were drawn from Chaliapin’s work.

A sense of the range and power of Chaliapin’s repertoire can be gleaned from a visit to his house-museum on the Garden Ring. The top floor includes a gallery of costumes and photographs.

Making War On Routine

Source: RIA Novosti

The Moscow Art Theatre first opened in the Hermitage Garden with a repertoire that included classic dramas by Shakespeare and Sophocles and, of course, Chekhov’s The Seagull. The premiere of The Seagull in imperial St. Petersburg had been a disaster and Chekhov was reluctant to see it staged again, but Nemirovich-Danchenko wrote to him describing how their new theater was full of “fresh talents” who were “making war on routine.” The play was so successful that the audience insisted a telegram be sent to the author to congratulate him.

After All We Have Lived Through

Source: RIA Novosti

In the museum above the MKHAT theatre on Kamergersky Pereulok, where the company relocated in 1902, you can trace the theatre’s long tradition from its roots through the turbulent 20th century.

In a letter of 1923, Stanislavsky complained that the theater had become increasingly unpopular as a bourgeois institution (quite an irony after its radical beginnings). “They think we are rolling in dollars,” he wrote, “when actually we are up to our ears in debt.” Plays by Chekhov and other intellectuals were popular with “Russian émigrés and American capitalists” and, for precisely that reason, became less popular with the Soviet authorities. The truth was that by this stage, Stanislavsky was also disenchanted with the endless productions of Chekhov’s plays.

Source: RIA Novosti

“After all we have lived through,” he is said to have remarked to Nemirovich-Danchenko about Three Sisters, “it is impossible to weep over the fact that an officer is going and leaving his lady behind.”

It was around this time that Stanislavsky moved into the 18th-century mansion on Leontyevsky Pereulok, where he spent the last years of his life. The house is now a wonderful house-museum with painted ceilings, carved wooden furniture, and a potent atmosphere. There are explanations in English in each room.

Under The Sign Of The Seagull

Source: RIA Novosti

After the initial triumph, the seagull became the theater company’s emblem. The stylized art deco emblem, designed by the architect Fyodor Shekhtel, adorns the graves of the many MKHAT company members buried in the Novodevichy Cemetery. Stanislavsky is in the row just behind Chekhov.

Stanislavsky’s legacy lives on in Moscow as elsewhere. There are three theaters named here after him and – more importantly – his techniques, aimed at producing psychologically convincing characters on the stage, have never gone out of fashion.

Originally published in The Moscow News.

Addresses:

1) Stanislavsky house-museum, 6 Leontyevsky Per. 6, m. Pushkinskaya

2) Moscow Art Theatre (MKHAT) museum, 3a Kamergersky Per., m. Teatralnaya

3) Chaliapin Museum, 25 Novinsky Bulvar, m. Barrikadnaya

All rights reserved by Rossiyskaya Gazeta.

This post originally appeared on Russia Beyond on January 17, 2013 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Phoebe Taplin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.