A throng of reporters circled Kristine Li at the officiating ceremony of H Queen’s, a gleaming new tower filled with art galleries. Designed by architect William Lim, it was Li who spearheaded the project for her family’s company, Henderson Land. The much-touted complex now houses some impressive names in the global contemporary art world, with high ceilings and big, bright rooms designed specifically with galleries in mind–the sort of space that is extremely hard to find in this hyper-dense city, so many of whose problems come down to a lack of space.

Li is the granddaughter of property tycoon Li Shau-kee, one of Hong Kong’s richest men. She holds up well under pressure as she fields questions in Cantonese and English, reporters thrusting recording devices under her nose. The opening of H Queen’s comes at an especially interesting time for Hong Kong’s creative sphere. Five years after the arrival of Art Basel, a growing number of commercial galleries are trickling in from abroad, joining an assortment of local commercial and non-profit art spaces, as well as the rather rambunctious auction houses. Hong Kong has never been more coveted as a place to show and sell art. But the problem of space persists.

Michaël Borremans, Fire From The Sun, David Zwirner Hong Kong, 2018. Photo Kitmin Lee – Courtesy David Zwirner

Tall, smooth-talking David Zwirner is one of the new arrivals. He runs an art empire of such stature that he permanently occupies a place in the top five biggest art dealers in the world, often coming in second only to Larry Gagosian. When he came to Hong Kong to open a new outpost in H Queen’s, he described the decision to set up camp here as a no-brainer. Though Beijing and Shanghai both have lively art scenes and a growing base of collectors, Zwirner was drawn to Hong Kong in part because of the freedoms that still exist here. As a gallerist with a fondness for putting on provocative, polarising shows, that decision seems wise.

Zwirner’s first show was a controversial exhibition featuring dismembered, bloodsoaked babies depicted with Goya-like oil brushwork by Belgian artist Michael Borremans. The horror those grim infants elicited in Hong Kong audiences has lingered. Some spectators reveled in the show, which was vehemently un-decorative, and which spoke to anxieties surrounding where humanity is headed that resonate globally, particularly in the wake of the maddening news cycle coinciding with Trump’s presidency. Other spectators described feeling unsettled–and not in a good way.

“Everyone is really enamored with Zwirner. He’s like the Gucci of the art world,” said one longtime local gallerist who asked to remain anonymous. “But what did that show have to say to Hong Kong people? How did it relate to them at all?”

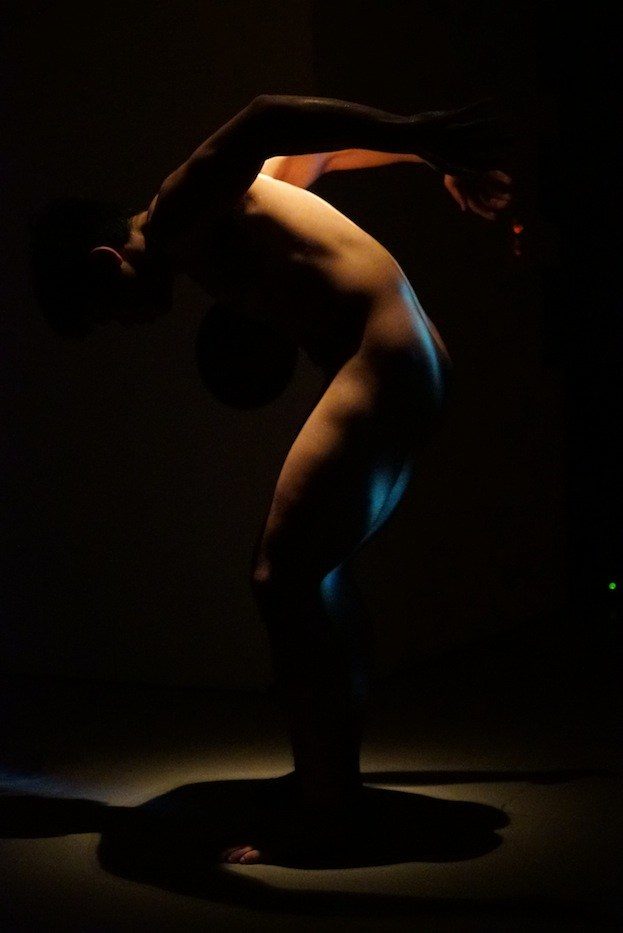

- Wu Tsang Dulian – Spring

- Josh Serafin with Happ’Art – Spring

- Industrial Forest mushroom – Spring

There are other complaints that come with the international hotshots and big art brands that have installed themselves on Hong Kong turf. Along with Zwirner, other blue-chip transplants include Hauser & Wirth, Pace, Gagosian, White Cube, and Lehmann Maupin, to name just a few. The ratio of market-driven international galleries to non-commercial spaces seems to be more out of balance than ever before. And Hong Kong has never enjoyed a particularly healthy art ecology, thanks to its paucity of museums.

Kristine Li says Henderson hopes to counter this by supporting arts education and programs to develop public art. The developer played a big role in supporting a temporary sculpture park along Victoria Harbour that saw local artists showcase works alongside an impressive billing of international artists. The motivation for such a project was not only to offer local artists a platform among international stars but also to take world-class art out of galleries and into the public realm.

That’s a global trend; as the value of the art market soars to ever more stratospheric levels, there is an impulse to at least be seen as democratizing it. But the sculpture park also speaks to another trend. Hong Kong’s economy is dominated by big property developers, and more and more of them are looking to become patrons of the arts by investing heavily in public art and exhibitions. This extra funding has been a boon for artists, but it is also an opportunity for society’s most powerful people to to co-opt art as yet another way to spread their influence, cementing existing power structures.

Few would argue that exposure to more meaningful, high calibre art will do harm to the public. “I think it’s great that young Hongkongers are getting to see more art than ever before,” says Catherine Kwai, who opened longstanding commercial gallery Kwai Fung Hin in 1993, at a time when opting to work in the arts was a life choice that raised eyebrows. Like other gallerists in Hong Kong, she started out in the financial sector, rekindling her childhood passion for art after she had her first child.

Since Kwai opened her gallery—a space that focuses on Mainland Chinese artists alongside some European and Chinese diaspora artists—attitudes towards the arts have changed dramatically, with Kwai noting that it is not unusual to find parents who now support their children’s dream to make a career out of art. Ever-pragmatic Hong Kong is coming round to the idea that the creative industries might provide viable career paths, and may even provide a sustainable future for a city whose core industries are in ruthless competition with mainland China.

And yet it is far from easy to make a living as an artist in Hong Kong, with a high cost of living and few platforms for emerging artists to make themselves seen. Compared with mainland Chinese and international artists, Hong Kong art isn’t especially valuable on the market, and many—if not most—established local artists supplement their income with teaching jobs that take them away from their studios. Another criticism voiced about Hong Kong art is that it tends to be rather trend-oriented, with artists regularly flitting about from discipline to discipline, leaving not much time to build craft or a cohesive voice. Artists have to be prolific jacks-of-all-trades, showing prowess and adaptability in installation work, video art, performance art, and sculpture as they pursue the attention that garners the right press, patronage, representation, and ideally, a sustainable income.

Soul Is Like Wind; Life Is Like Snow: Recent Works of Ai Xuan – Courtesy Kwai Fung Hin Art Gallery

The commerce-driven quality of the art scene also threatens artists’ ability to express themselves in a genuine way. Kacey Wong is one artist who is particularly concerned with this problem. He notes that more and more artists seem to be producing works that are purely decorative; they avoid challenging the status quo, lest they lose the favor of their corporate patrons. This pressure to make profitable art dilutes the quality of the art scene, pushing up the prices of unchallenging art without providing real, long-term cultural significance. That’s why a diverse art ecology in which non-profit spaces can support art, experimentation, and self-expression without being overly beholden to commercial and short-term interests are so important to the cultural vibrancy of a city.

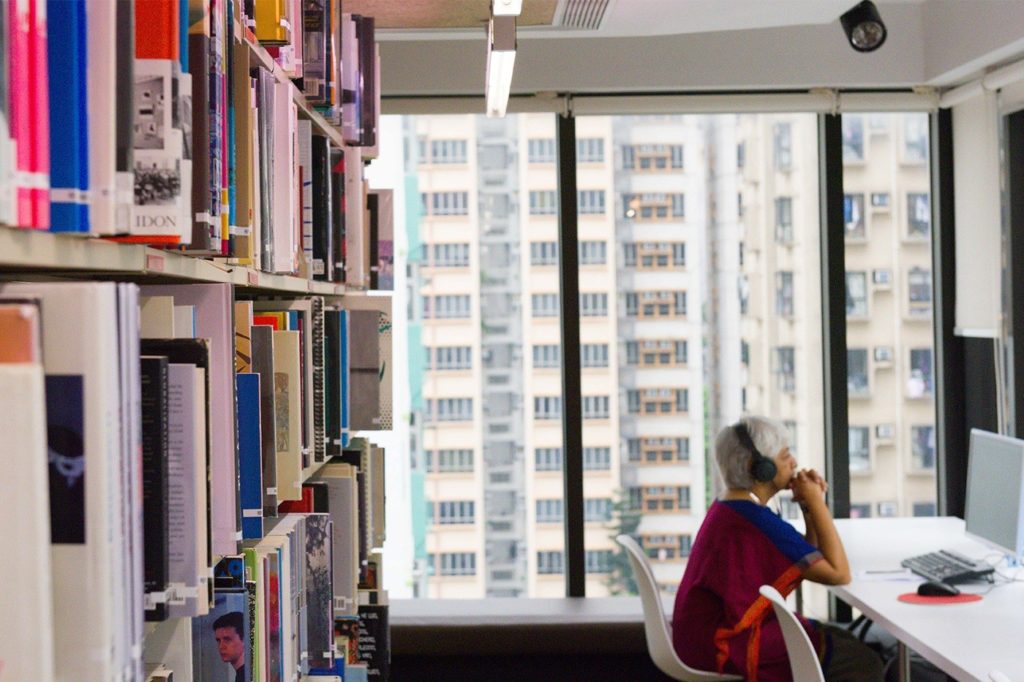

It’s something that concerns Mimi Brown, whose five-year project, Spring Workshop, was one of Hong Kong’s most vibrant art spaces. After Brown arrived in Hong Kong from California in 2005, she became involved with non-profit organizations Para Site and Asia Arts Archive, both of which are crucial to the city’s cultural sphere, even though high rents have forced them into discreet locations inside tower blocks. Brown launched Spring in 2011, and over the next five years, it developed a broad and ambitious program that created cultural collisions between artists in Hong Kong and abroad. With numerous artist residencies that drew filmmakers, curators, musicians, and writers, it cultivated an atmosphere of experimentation and play alongside intellectual rigor, with a collaborative spirit that invited creators to genuinely pursue what is meaningful to them and their practice.

“The main problem for non-profits in Hong Kong is space,” says Brown. “For example, there are organizations like Asia Art Archive, which is a world-class organization, that can’t find an adequate home for its exceptional holdings, team, and programs. This surprises me, as one would imagine there would be landlords here who would be delighted to sponsor so precious a tenant.” Tied in with that problem is a lack of interest in non-profit spaces–“or even necessarily in the distinction between commercial and non-commercial spaces,” she says.

Asia Art Archive – Courtesy AAA

Earlier this year, Spring closed its doors, and its Wong Chuk Hang space is now being occupied by a coworking franchise. In recent years, the neighborhood’s industrial blocks have filled up with art galleries, blossoming into Hong Kong’s largest art enclave. But this has inevitably created a surge of interest in the area, and as rent rises, studios and other art spaces may be forced out. These are some of the many challenges Hong Kong artists face as their stomping grounds become increasingly inundated with international players eager to enjoy their stake in the global art market.

For all these challenges, though, Hong Kong’s art world is not without hope. Two major new institutions, the M+ museum of visual arts and the Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage and Art, will open over the next two years. While non-profit spaces will still be needed, the museums will help offset the imbalance in art ecology still weighing too far in favor of commercial forces.

One art world mover and shaker who is particularly excited to see the city enter this new chapter is Doryun Chong, chief curator at M+, who took on the role after a stint at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Chong says he was eager to come to Hong Kong at this point in its unfolding art chapter. “We have been in the midst of a seismic shift,” he says. “There is absolutely no doubt that Hong Kong will be one of the leading hubs for art in Asia, for many different reasons. We’re witnessing a new crop of commercial galleries, but others were there before, and small non-profits have been here for a long time. All layers of the art ecology have grown exponentially over the last few years.”

Asked about the threat of Hong Kong’s art scene leaning too heavily towards the commercial, Chong brings up a curious metaphor, likening Hong Kong’s cultural trajectory to the growth spurts of a teenager. “Different parts of your body grow at different rates,” he says. “Teenagers are so awkward, but when they reach the end of puberty their bodies find a balance. There is no correct formula for growing a city’s art ecology.”

But if the arrival of H Queen’s and the impending opening of M+ are signs of the art scene being in its teenage years, what does adulthood hold for Hong Kong? That’s a trickier picture to paint, especially in these disorientating, hyperconnected and rapidly-transforming times we live in, where everything and nothing seems possible.

This article was originally written by Sarah Karacs for Zolima Citymaon March 29, 2018. Reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Zolima CityMag.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.