During the AAPI (Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders) heritage month, let us explore the fascinating works by East Asian directors and actors. The AAPI month honors the living, hybrid Asian and Western cultures. Since the nineteenth century, there have been hundreds of adaptations of Shakespeare drawn on East Asian motifs. Gender roles in the plays take on new meanings when they are embodied by Asian actors, and new accents expanded the characters’ racial identities in this age of globalization.

What’s in a name? Everything!

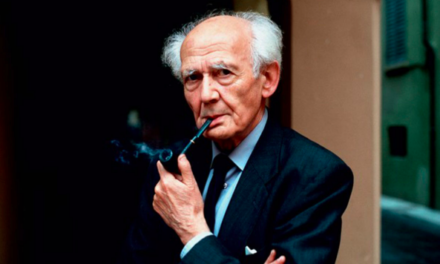

Oh Tae-suk’s Romeo and Juliet (Mokhwa Repertory Company), one of the earliest mainstream South Korean productions of Shakespeare to tour the United Kingdom, is a landmark in the history of post-1990 Korean theatre. It toured to Bremen in 2001 and London in 2006. The highly stylized production was characterized by aesthetics of self-restraint. Oh prioritized stillness overdramatic explosions of emotions. Dance and stylized, symbolic fight scenes replaced shingûk (new, modern theatre) and Stanislavski-inspired psychological and dialogue-based realism. A martial dance expressed the mutual hostility between the Montagues and Capulets without words.

Romeo and Juliet, directed by Oh Tae-suk, Mokhwa Repertory Company.

Gender roles have been reimagined. The scene of Romeo in Juliet’s bedroom played out with a heightened sense of frustration. The stage was covered with a gigantic white bedsheet, and Romeo spent a good part of the scene hunting down Juliet as she scurried under the sheet. He never successfully undressed Juliet and struggled to even remove her socks even when she willingly offered her leg. The adaptation reminds us that Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet itself is peppered with fast-paced, improbable plot developments that are closer to fables.

From Cinematic Stage to Theatrical Screen

In Asian performance histories, there are deep connections between theatrical and cinematic performances. Many adaptations experiment with features of both conventions and ask metatheatrical questions.

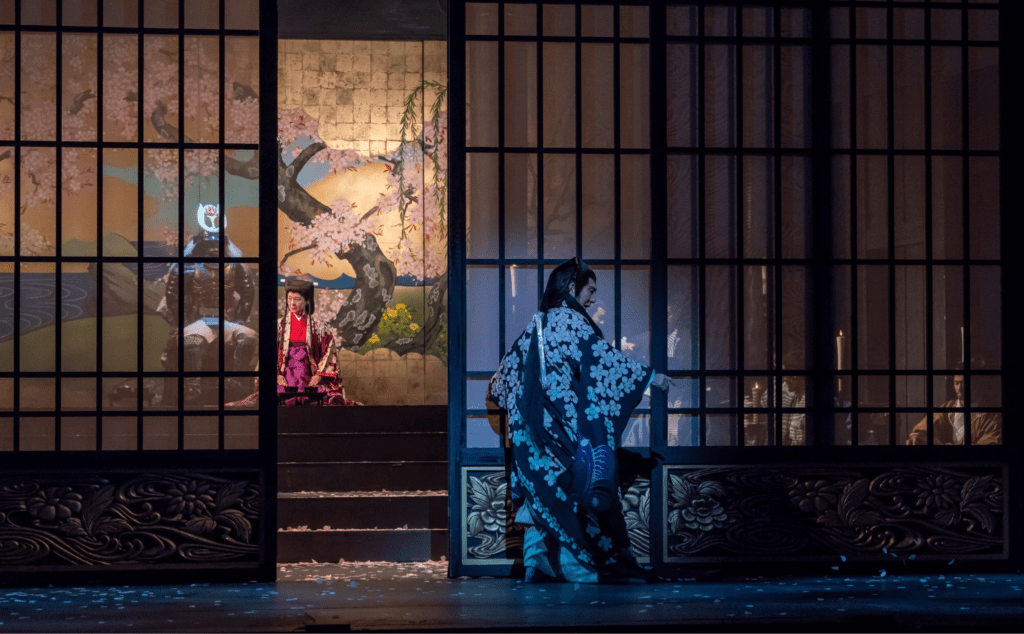

Filmmaker Akira Kurosawa, for example, used traditional Japanese theatrical elements in his cinematic depictions of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth in his samurai film Throne of Blood (1957). Kurosawa’s signature long shots, which remain emotionally detached, are echoed in Yukio Ninagawa’s stage version of Macbeth, particularly in scenes played behind semitransparent screen doors. Ninagawa was well known for the cinematic quality of some of his stage productions, and Kurosawa derived inspiration from Noh and Kabuki styles of presentation and makeup.

Macbeth (dir. Yukio Ninagawa, Lincoln Center New York, 2018). Semitranslucent screens.

The theatre—as a profession and genre—occupies a central place in the Hong Kong comedy film One Husband Too Many (dir. Anthony Chan, 1988). The rustic stage where the play within a film is mounted serves as both a dramatic device and a venue where cultural values are negotiated. The film follows a couple aspiring to introduce Western culture to backwater Hong Kong through their iffy performance of Romeo and Juliet. The couple’s performance is an imitation of Franco Zeffirelli’s 1968 film version. Comedy arises from the protagonist’s Quixotic insistence on staging Shakespeare for enlightening messages. The film and the play-within-the-film grinningly contrast the contrivance of Zeffirelli’s film with any fantasy that the allegedly greatest (British) love story of all time can ameliorate social conditions in Hong Kong.

Shakespeare to the rescue? Not always

Many adaptations depict the idea that performing Shakespeare can improve not only local art forms (such as attracting a larger audience or securing invitations for international festivals or tours) but also personal and social circumstances (such as addressing issues like trauma or voicing political opinions that are otherwise difficult to discuss publicly). Around the world, Shakespeare has been imagined to have a reparative effect on the artist’s or a society’s outlook on life when the time is “out of joint” (Hamlet, 1.5.190) or during identity crises. While the canonical status of Shakespeare’s oeuvre has led to admiration and deference, there have been many witty parodies of the tragedies.

Some adaptations are built on the assumption that performing Shakespeare can improve one’s moral character (such as Wu Hsing-kuo’s Buddhist-inflected solo production of King Lear in 2001 and 2007), but other works mock the conviction that Shakespeare has any recuperative function in the society (such as Lee Kuo-hsiu’s Shamlet (1992) which mocks Western realist performances and turns high tragedy into comic parody).

One memorable parody of the idea of “reparative” Shakespeare is Chee Kong Cheah’s Singaporean film Chicken Rice War (2000). Built around the conceit of a college production of Romeo and Juliet, the film trivializes the feud in Romeo and Juliet by reducing the generations-old dispute, to the rivalry between the Wong and Chan families, who own competing chicken rice stalls. The film’s opening and closing scenes, narrated by a news anchor, simultaneously parody Shakespeare’s prologue, epilogue, and Baz Luhrmann’s film William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet. Performing Shakespeare’s play fails, in the end, to resolve the hostility between the two families—both alike in indignity.

Vincent Chan contemplates, at his chicken rice stall, the rivalry between the Chan and the Wong families. Chicken Rice War, directed by Chee Kong Cheah (2000).

Caption: Vincent Chan contemplates, at his chicken rice stall, the rivalry between the Chan and the Wong families. Chicken Rice War, directed by Chee Kong Cheah (2000).

Sounding racial differences

Race and ethnicity are not only visible but also audible in these adaptations. The aforementioned Chicken Rice War uses multilingualism as both a dramatic device and a political metaphor. The elder generation converse in Cantonese whilst the younger generation speaks mostly Singlish, or Singaporean English. Fenson and Audrey, in a mix of English and Cantonese, perform the “balcony” scene, in which Romeo and Juliet meet after the masked ball.

Meanwhile, their offstage parents become more and more impatient with their public display of affection, not understanding the boundary between play-making and playgoing. The parents are emotionally detached from and intellectually excluded by the younger generation’s Anglophone education, symbolized by their (unsuccessful) enactment of Shakespeare.

In Singaporean director Ong Keng Sen’s pan-Asian production of King Lear (1997 and 1999), Chinese, Japanese, Thai, and Indonesian actors perform characters who speak a range of different languages. The Old Man (Lear) walks across the stage in the solemn style of Japanese Noh theatre. He chants, “Who am I?” in Japanese. A cross-dressed figure in Beijing opera costume, the Older Daughter (a composite figure of Goneril and Regan), approaches him and answers in Mandarin in a stylized high-pitched voice: “Fuqin. Nin shi wo de fuqin [Father. You are my father].” After pointing out that a father is the one who creates her “from a drop of [his] love,” the Older Daughter shifts the focus to herself, to the question of who she is. The confrontation between the Japanese-speaking patriarch and his Mandarin-speaking daughter brings to mind the Sino-Japanese conflicts throughout the twentieth century.

A pan-Asian Lear directed by Ong Keng Sen, TheatreWorks, Singapore, 1997.

Singapore’s propaganda emphasizes commercial cosmopolitanism and transnational histories of immigration in the service of economic growth. Chicken Rice War and the pan-Asian Lear critique the idea that “sounding white”—speaking standard English—conveys more authority.

Deep connections among different cultures

This performance history shows that there are deep connections among Asian and Anglophone performance cultures. For example, Peter Brook’s production of Titus Andronicus (1955) in Stratford-upon-Avon (starring Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh) replaced conventional, naturalistic portrayals of horror with Asian-inspired stylization (such as scarlet streamers signifying Lavinia’s rape and mutilation) and an abstract, minimalist set. Brook’s work anticipated the use of red ribbons to symbolize blood in Yukio Ninagawa’s production of the same play in 2006 as part of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s Complete Works festival.

Lavinia in “Titus Andronicus”, directed by Yukio Ninagawa, 2006.

Chicken Rice War pointedly parodies Luhrmann’s campy film adaptation of Romeo and Juliet. The Hong Kong comedy film One Husband Too Many (1988), directed by Anthony Chan, features costumes reminiscent of Danilo Donati’s doublet-and-tights designs for Franco Zeffirelli’s film Romeo and Juliet (1968) to the tune of that film’s “A Time for Us” by Nino Rota, with new Cantonese lyrics.

These rich cross-references suggest that adaptations of the Western canon have intraregional and global significance. Non-Anglophone Shakespeares are not antithetical to English-language performances; both must negotiate pathways to contingent meanings through transhistorical and cross-cultural axes. All performances are best understood in a comparative context.

English speakers tend to be accustomed to thinking of Shakespeare performances as narratives whose meanings are governed by chronological events—something that unfolds chronologically (Lear’s gradual descent into madness follows the division of his kingdom). Some of these creative adaptations deal with symbols rather than linear narratives. They share echoes of Shakespeare’s lines or imagery, but they also draw on audiences’ awareness of previous adaptations.

These adaptations break new ground in sound and spectacle. They serve as a vehicle for social reparation. They provide a forum where artists and audiences can grapple with the contemporary issues of racial and gender equality, and they forge a new path for world cinema and theatre.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Alexa Alice Joubin.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.