Would you go and see a bilingual or multilingual show if you only spoke one of the languages staged? What if by going, you could open your mind not just to a new language, but also a new culture?

In New Zealand, it is rare to see theatre performed in New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL), and rarer still to see it performed through the hands of a first language user.

Award-winning theatre company Equal Voices Arts has developed two original shows performed in both NZSL and New Zealand English (NZE) to enable both Deaf and hearing audiences to share the experience.

Sign and spoken language share stage

In New Zealand, around 25,000 people use NZSL. It is one of two official languages, alongside te reo Māori. English may soon be added as a third official language through Bill Clayton’s proposed bill.

Despite its status, NZSL doesn’t have as much visibility in mainstream cultural settings as many would like to see. In contrast, NZE is so widely spoken that it does not seem to need official status or designation.

Many people who use NZSL as their first language have had to learn how to interact within the predominantly hearing world around them, where speech is, sadly, an assumed default. Many Deaf people have developed superior communication skills in order to function in a world where speech dominates. They are well versed in looking for contextual cues to make sense of a language they themselves do not use.

An understanding of hearing culture is common in the Deaf world, but the reverse is not often the case. What is a common path for Deaf NZSL users is completely new territory for many hearing English speakers. In a signed-spoken bilingual theatre production, it is over to the hearing audience to look more closely, to make sense of the physical language they see on the stage, and to witness the expressiveness and power of NZSL. Here, NZSL and spoken English have equal status.

Read more:

A Great Year For Signed Languages In Film–And What We Can Learn From It

Grammar and use of sign language

NZSL comes with its own lexicon, grammar, and linguistic variation. For example, like spoken NZE, NZSL includes phrases that are expressed by manually signed words as well as emphatic discourse features, which are expressed through facial gestures and body posture. The latter is usually conveyed through stress and intonation in spoken English.

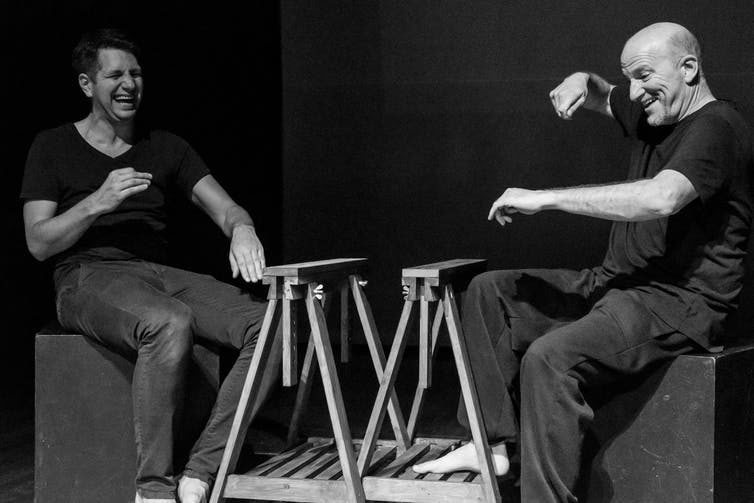

Physical storytelling comes naturally to Deaf actor Shaun Fahey.

Michael Smith, CC BY-SA

Because NZSL and NZE are separate languages, with distinct origins, they also differ in a number of important ways. One aspect is that words don’t always match and sentences cannot be translated word-by-word from one language to another. To this effect, researchers David McKee and Graeme Kennedy have identified that the most frequently used signs in NZSL are very different from the most frequently used words in NZE.

One such difference is the preference for verbs (action words) in NZSL, with signs for “go,” “say,” “work,” “see,” “know,” “want,” “look,” “come,” “feel,” “write,” and so on, being used much more frequently than the equivalent words in spoken English. On the other hand, NZE exhibits a higher rate of function words, whose job is to indicate a grammatical role, such as tense markers. Spoken NZE loves words like “the,” “a,” “do,” “have,” and “be.” In contrast, NZSL achieves these linguistic functions by other means, for example, by using physical space to create different points in time.

Another example is the fact that the order of signs in NZSL is unlike that of words in NZE. A sentence like “I have finished reading the thick book” in English would be expressed by the following order in NZSL “I read book thick finish.”

Blending languages on stage

NZSL and NZE are linguistically very different. But like in any other multicultural setting, the language itself is only one aspect that contributes to a greater sense of cultural awareness, sharing and mutual respect. It seems logical then that a step towards bridging the distance between these two languages and cultures should be to provide opportunities for shared experiences and a common physical space in which both languages can enjoy an equal sense of entitlement, importance, and belonging.

The theatre company Equal Voices Arts sets out to do just that. Their touring productions have included Deaf and hearing performers and have been developed to be accessible to both Deaf and hearing audiences.

The decision not to interpret everything seen on stage into either language was deliberate. In each production, there were sections in NZSL without English translation and vice versa, but with sufficient contextual cues for both the Deaf and hearing audiences to follow the narrative, and to engage directly with the characters on stage.

Efforts were made to provide spaces with no official language, based on concepts such as “visual vernacular” (VV), a term coined in a theatrical context by American Deaf actor Bernard Bragg. Playwright Kaite O’Reilly, whose work has inspired Equal Voices Arts’ approach, explains that VV is “not sign language nor mime, but something in between.”

As Jean St. Clair outlines, VV comes from the “concept of looking at the world in a visual way, and to capture the images using facial expressions, hand movements and body language.” It can use film techniques such as close-ups and different camera angles to focus the audiences’ attention.

Visual storytelling

This form of physical storytelling comes naturally to Deaf actor Shaun Fahey, despite having no formal theatre training before he started work on productions with Equal Voices Arts and director Laura Haughey. Serbian actor Mihailo Lađevac (hearing), who brings more than 20 years of professional acting experience to these productions, learnt from Fahey’s physical storytelling in rehearsal, just as Fahey learnt from Lađevac’s depth of expertise. With neither actor having English as a first language, they started exploring ideas using only physical storytelling and mime.

The visual vernacular developed for the theatre company’s second production Salonica was born in this interaction between Deaf and hearing worlds, borrowing conventions from sign languages and adapting them for creative expression on stage. Both actors created a shared spatial and physical language on stage which was a new experience for Lađevac, but one that came very naturally to Fahey. This is an example of “Deaf gain,” a concept coined to reframe perceptions of deafness to examine gains brought about by diversity.

Two languages, one stage, one society

For some members of the Deaf audience, it was the first time they were able to access theatre in their own language, performed by first language users alongside hearing audiences. Similarly, for many of the hearing audience, this was the first time they had seen NZSL on stage.

The physical space created by the theatre stage acts as a linguistically shared space in which audiences are challenged to use every power at hand to make sense of a language they do not converse with. This is an everyday experience for Deaf NZSL users, who often have to draw on their skills to lip read or use contextual and non-verbal cues to communicate. The experience may be a completely new task for hearing non-signers–and the challenge is a step towards cross-linguistic exchange and a more informed society.

As a review of At The End Of My Hands by Dr. Alys Moody in Theatre Journal states:

the production suggested that theatre can provide a unique medium for staging the encounter between spoken and signed languages, and that the stage, as a site of gestural and embodied expression, permits the two languages to become mutually intelligible.

![]() The authors would like to warmly acknowledge the Equal Voices Arts team and all collaborators, and the work of Oddsocks Productions and Giant Leap Foundation for their work with Deaf and hearing artists.

The authors would like to warmly acknowledge the Equal Voices Arts team and all collaborators, and the work of Oddsocks Productions and Giant Leap Foundation for their work with Deaf and hearing artists.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Andreea S. Calude, Laura Haughey, and Kellye Bensley.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.