In his latest premiere, Koprofagi, Jan Klata abandons all the strategies that secured him his current position in Polish theatre. Sadly, it seems there is little left once the flashy façade has been removed.

It is certainly a difficult and artistically risky decision for a director to abandon his previous path and signature style. Every experiment involves an inherent element of risk—an element that artists are rarely willing to take into consideration.

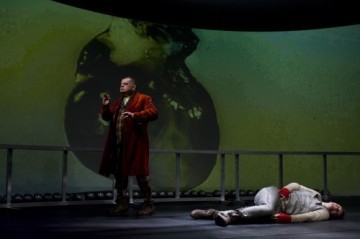

The piece consists of two parts, each telling separate stories but sharing such themes as secret agents, informers, challenging the system, and terrorism. Both parts take place in identical spaces: a semi-circular back wall onto which black and white images and footage are constantly projected—from landscapes and insects to the interiors of fascist headquarters. A round stage, resembling a pocket watch with no face, is suspended above the stage. Every now and again the contraption is set in motion; the gear slowly turns, signaling the passing time, the imminent end, and the wheel of history.

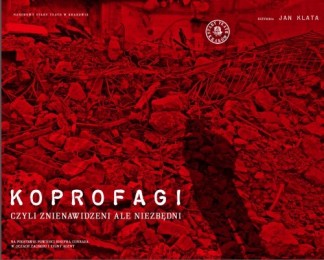

Koprofagi, czyli znienawidzeni ale niezbędni (Coprophagists, or the Hated Yet Indispensable), based on the novels Under Western Eyes and The Secret Agent, by Joseph Conrad. Directed by Jan Klata. Stary Theatre in Kraków.

Part one opens with a political annunciation: Wiktor Haldin (Zbigniew W. Kaleta), wearing wings of iron, reports to Razumow (Juliusz Chrząstwoski) about the successful assassination of a minister who had—in his opinion—been working to the detriment of the economy and the state. Razumow is implicated in the assassination, arrested, recruited, and sent to Switzerland as a government spy to infiltrate a group of anarchists who view Haldin as a hero. Razumow humbly undertakes the mission, but once he arrives in Switzerland, he falls in love with Haldin’s sister and, stirred by emotions, admits to being an agent. The group of anarchists is led by Piotr Iwanowicz (Krzysztof Globisz), a man with an aristocratic air who speaks in a slow, weak, barely audible whisper and requires constant care due to his disabilities. The group shares a characteristic demeanor, which—in the director’s mind—serves to unify their members: the constant drinking of tea and smoking of electronic cigarettes. Initially frightened and confused, Razumow quickly abandons his role as a spy, choosing instead to enjoy long walks with Natalia Haldin (Anna Radwan-Gancarczyk).

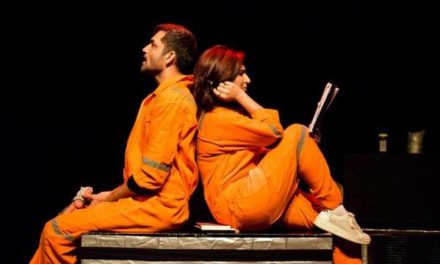

In part two, the secret agent Verloc (Krzysztof Globisz) is given the mission of blowing up the Greenwich Observatory after years of fruitless labor. He is not only an agent but also the husband of Mrs. Verloc (Ewa Kaim). The couple lives with her mentally handicapped brother Stevie (Wiktor Loga-Skarczewski), who treats Verloc as a father. Verloc co-opts his brother-in-law into the terrorist plot, but the boy trips while carrying the explosives and is killed instantly. Desperate, Verloc tries to figure out how to break the tragic news to his wife, who finally discovers the truth and murders her husband.

Both parts of the piece take place in the realist plane. The actors try to create psychologically convincing characters, drawing out their sentences and overemphasizing dramatic pauses in dialogue. In Klata’s earlier performances, such techniques were used intentionally to highlight or subvert the convention. Their use in Koprofagi seems conscious and very serious, just like the linear narration and the logical transitions between scenes. Unfortunately, none of the actors appear truly comfortable with the melodramatic dialogue, some of which resembles plays by Jon Fosse. In the long scenes with Razumow and Natalia, both Chrząstowski and Radwan-Gancarczyk come across as insincere, as if they were incapable of communicating. Razumow sighs lovingly at Natalia, while she bursts into tears upon hearing of his betrayal of Haldin, wiping her tears with a handkerchief. And yet both have proven, on numerous occasions, to be masters of formal performances, capable of building original characters without relying on psychological drama. Suffice it to mention Klata’s Kraków performances (paradoxically enough): Oresteja, Trylogia, and his recent premiere, Wesele Hrabiego Orgaza. Koprofagi, in contrast, has the pair using unbearable mannerisms, skimming along the surface of words that come together to produce pretentious dialogue and fail to build any tension between the characters.

Klata has also given up on the dance sequences and musical samples that often imbued his performances with impressive power and rhythm. All of this has been extinguished, leaving mere hints: the drunken Ziemianicz who comes to Razumow for help, staggering around the stage to the accompaniment of a choir, stumbling onto Razumow, and rolling over his back; the participants of the political meetings attended by Verloc spin hula-hoops around their necks. These clear yet weak signals leave no room for the actors to develop their characters, nor for the audience to interpret them within a broader context. Most of these tactics seem superfluous and tacked on as an afterthought.

The juxtaposition of the two parts doesn’t contribute anything, either, as there is absolutely no difference between them in terms of performance. Klata’s apparent aim was to universalize the chronologically-distant stories, yet his observations are hardly insightful. They’re not even innovative when compared to Klata’s own work: he has already covered the themes of revolution and history in Sprawa Dantona and Trylogia. The statements posed in those pieces were powerful and sparked debate. No single topic takes center stage in Koprofagi; there’s no concept to consolidate the scenes, which drag on endlessly and predictably. The actors play out one situation after another, developing the plot without building the characters. As a result, the actors’ performances are monotonous and indiscernible, despite playing different roles in each part.

Klata’s undoubted intention was to use the two Conrad novels to tell a complete story with a beginning, middle and end. In doing so, he explores such themes as terrorism, the innocence of assassination victims, rebellion against the system, and government agent networks. But he stops short of any radical statements and avoids the enormous theatrical potential that lies in these topics. Klata has assumed the difficult task of abandoning his previous directorial style, but one wonders why he has stubbornly chosen to explore these subjects solely through a psychological lens. Especially since most scenes give us little clue as to the topic at hand or what goals the director has given the actors. Perhaps Klata felt the need to explore new directions in which to take his theatrical work. As an experiment in Klata by Klata, Koprofagi is a failure. The director has abandoned the very strategies that secured him his current position in Polish theatre. Sadly, it seems there is little left once the flashy façade has been removed.

Translated by Arthur Barys

This post originally appeared on Biweekly.pl in October 2011 and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Marta Bryś.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.