This weekend see a play about the Internet age with Orwellian subtexts and an experimental Chekhovian comedy.

Ten-odd shows after opening at last year’s NCPA Centrestage—which might have well been the final edition of the festival of premiering plays—Story Circus’ I, Cloud will return to the alternative spaces circuit this weekend. Directed by Ulka Mayur, the play’s starting point was Kalidasa’s Meghadūta, in which a passing cloud is convinced to relay a message from an exiled yakṣa to his beloved. Mayur fashions the messenger cloud as a digital entity, clearly a metaphor for the Internet or social media, with its vast network of interconnected systems. Rather than a run-in with the god Kubera, as in the original, the circumstances of the protagonist’s exile are linked to a stint at a “like factory” where he cannot quite keep up with a digital culture of instant affirmation and is banished for penning a purportedly anti-national poem.

Insidious agendas

The play features Mayur Puri as Yakṣa and Shashaa Tirupati as his muse, Kavya. The tangerine overalls they wear in the play are reminiscent of Guantanamo Bay, which Mayur terms purely coincidental, even if oppression by the powers-that-be provides the play its central conflict. While it does share structural similarities with Meghadūta, it is ultimately an original piece set in the future. Mayur herself plays the Cloud as a tapori-style character. Deep into its run, the play continues to evolve, because Mayur considers her theatre pieces as perennial works in progress— although overriding structures are put into place early. “It’s similar to how a film is redesigned on the editing table,” she says.

The very notion of a “like factory” recalls social media cells and the machinery of propaganda thriving on virality, and Mayur is well aware of this Orwellian subtext. It plays out as an undercurrent, inspired by the assassination of Gauri Lankesh, but Mayur was interested in fashioning a play that wasn’t in-your-face, but subtle, and therefore more in line with the insidious agendas that pervade our lives.

Experiments in comedy

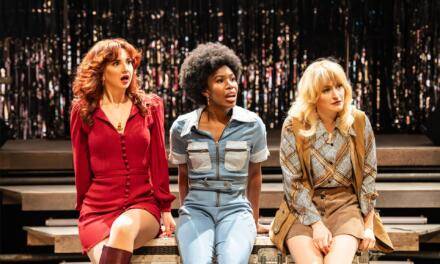

Another classic that will receive a makeover this weekend is Anton Chekhov’s one-act farce The Proposal, a play that is all of 150-years-old but still hasn’t arrived at its sell-by date. It is essentially a hysterical comedy of errors spawned by a suitor’s misguided attempts to request the hand of his neighbor’s winsome daughter, despite persisting bad blood from the past. Directed by Tushar Dalvi, this will be Rangaai Theatre Company’s third immersive outing, after The Darkroom Project 2.0, in which stories by well-known writers were effectively delivered to the underbelly whence they emerged, and Untitled, which examined the intrusiveness of sexual violation through hard-hitting stories like Franca Rame’s The Rape. This time around, keeping the original’s narrative integrity in mind, the immersive and interactive elements are restricted to the beginning and the end of the play—the audience enters a space filled with the rhythms and bonhomie of a North Indian sangeet ceremony. The play will be a 360-degree experience performed “in the round,” and the actors will frequently “break the wall,” a common trope in broad comedy. As is evident, names and cultural contexts in the original have been changed to better suit local audiences. Dalvi is one in a growing tribe of immersive theatremakers of markedly differing sensibilities in the country, whose practices have emerged quite independently of one another. It took him some persuading to get his ensemble around to experimenting with a new form, especially one that is rife with creative uncertainties, and audiences soon followed suit. The extended run that The Darkroom Project 2.0 has enjoyed in the fringe circuit has provided the group a fillip of sorts to continue in the same direction. “We are among the earliest groups to adopt several of the spaces currently functioning as arts venues,” says Dalvi of his part in supporting an eco-system in which experimental works by emerging artists can thrive.

This article appeared in The Hindu on October 12, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Vikram Phukan.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.