The Belarus Free Theatre, exiled from their home nation, has returned to Australia to collaborate with local theatre artists on a new political work, Trustees. The production begins with a hypothetical scenario in which the Australian government has placed a moratorium on public funding for the arts. While this scenario isn’t real, it cuts close to the bone after then-arts minister George Brandis gutted the Australia Council in 2015.

The production stages a public debate hosted by the (made up) Melbourne Trust Forum. It unfolds as part media reportage and part game show. The actors take on the roles of charismatic celebrity types, stalking the stage and encouraging the audience to register an online yes or no vote to the question “does government funding for the arts do more harm than good?” Several positions are thrashed out by the four celebrities who embody the spectrum of right-wing and left-wing commentary, in a parody of Australia’s own culture wars.

If not our poets and playwrights, argues one of the members of the trust forum, who or what forces will shape a cohesive and distinct Australian cultural identity today? As if such a thing were possible or even desirable. These arguments are not staged as earnest interventions, but rather as an absurd spectacle.

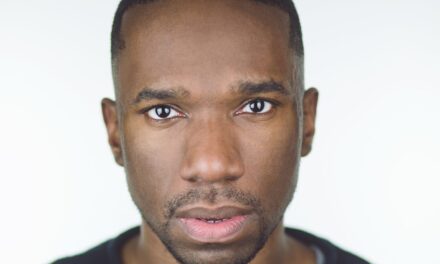

Natasha Herbert. Photo: Nicolai Khalezin

This staged debate becomes a decoy for exploring other structures of political disenfranchisement and privilege. For instance, can the debate over the arts be connected to Australia’s dehumanizing treatment of refugees and asylum seekers? While a direct link is never explicitly made, it is certainly intimated.

The stage, which until this point has been modeled on a TV studio, with its bright lights and cues for audience applause, is then transformed into a boardroom. Here, the trustees of the Lone Pine Theatre Company gather to elect a new CEO and decide on a survival strategy amid the wreckage of a defunded arts sector. A proposal for a new form of theatre is floated: an immersive playground housed in a multi-story building. It will host plot-lines and participatory experiences where jingoism might intermingle with a Kardashian style reality TV format: something to really make theatre profitable again.

The absurdity mounts. The trustees brainstorm underground levels where the violence of the Frontier Wars will be re-enacted in a kind of sexed-up colonial “Westworld.” The critique of arts funding is driven by cynical interpretations of what counts as innovation and diversity in Australian theatre is certainly not lost here.

The boardroom table is not what it seems in this production. Photo: Nicolai Khalezin

The increasingly debauched suggestions of the trustees create a tension and sense of complicity in its audience. We laugh at the trustees’ rising absurdity and self-exploitation, yet recognise our role as consumers of their commodifiable identities: a Palestinian man (Hazem Shammas), an Aboriginal woman (Tammy Anderson), a young Indian woman (Niharika Senapati), and as counter-point, two white characters (Daniel Schlusser and Natasha Herbert).

Then the mood shifts again, to great theatrical effect. Where in the earlier scene the audience was asked to take on the role of adjudicators in a failed debate on arts funding, we now became voyeurs. One of the trustees is to be elected as leader, and a choreographed leadership spill ensues where board members battle it out in a dirty power play.

Bridget Fiske’s movement direction comes to the fore here. Her stylised choreography captures the slow-burn horror of market-driven competitiveness in the arts. The tussle for power is expressed as a violent libidinized tango, intimating that power is not only synonymous with brute physical force but laced with sadomasochistic impulse.

As is to be expected, the white guy (Daniel Schlusser) wins. He mounts the boardroom table to give a terrifying victor’s speech with a recognizable reference to John Howard’s 2004 acceptance speech. The boardroom is suddenly transformed into a bizarre occultish space where the acceptable violence of Australian political and cultural life bleeds to the surface and the anti-racist platitudes of the liberal left are prodded and deflated.

Daniel Schlusser, as the victorious white guy, and Tammy Anderson. Photo: Nicolai Khalezin

It provides a surreal platform for the actors as they explore legacies of male anger and violence. The disturbing dynamics of white guilt are played out, political complacency is confessed, and theatrical traditions of exploitation of Indigenous women’s bodies are confronted head-on.

The production avoids the kind of earnestness that imbues much of political theatre. Is it didactic? Yes. But it also cuts through the turgid crust of fraught public debate over the arts and culture to create an atmosphere that verges on gothic horror. Unable to concede to the viewpoint that a distinction between left and right even exists, it asks us to imagine a post-political world. Here, freedom of speech no longer functions as the dignified ideal of the democratic institution but is captive to hellish modes of spectacular, and mediatized, presentation.

It asks us to imagine that we live in an oppressive echo chamber that resembles one of the rings of Dante’s Inferno, a purgatorial space of ritualized punishments. The only way out of this impasse of opinion and apathy, it seems, is to invoke chaos.

On this front, Hazem Shammas’ powerful incantations towards the end of the production will leave you reeling. With a kind of terrifying conviction, he speaks the unspeakable into the void of Australia’s political sublimations, jolting us temporarily out of our sense of complacency: “Fuck the Australian dream,” he tells us, “fuck Allah, fuck Christ, fuck white validation, withdraw, stay safe, stay comfortable.”

Trustees was staged as part of the Melbourne International Arts Festival.

This article appeared in The Conversation on October 8, 2018, and has been reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Sandra D'urso.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.