Belén Santa-Olalla has a BA in Media Practice and Theory from Sussex University, Brighton. She studied audiovisual communication, drama and performance art, and was an assistant director for the former director of the National Theatre and the National Dramatic Centre in Spain where she founded her own theatre company, Stroke114. As she became interested in the intersection of technology and theatre, she learned about transmedia storytelling and, due to her interest in post-production software and other technology, ended up working with Robert Pratten at Transmedia Storyteller Limited (www.conducttr.com) in London. Now, she works there as a creative consultant, focusing on adding a physical

Belén Santa-Olalla. Photo by Rodrigo de la Calva.

element to transmedia work.

AB: How do you define transmedia storytelling through your practice?

BSO: For me, transmedia storytelling has three core elements. The first one is that it is a narrative universe deep enough to give room to different stories, allowing creators to follow aesthetic or story world rules that give them a framework. The second is that we are looking at multiplatform storytelling, using different channels that complement each other to tell independent stories. I like to think as these platforms as windows, so you can just look at the world and that generates the idea of a rich and full universe. The third is that the users can interact with each other, so it is participatory (through co-creation or choose-your-own-adventure and community mechanics).

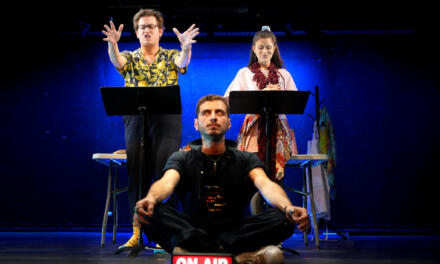

El proceso, de Kafka. Photo by Daniel Pérez.

AB: When you are working with your own company how do you use transmedia storytelling mechanics?

BSO: When I work with Stroke114, I tend to use transmedia storytelling. Our latest production was an adaptation of The Trial by Franz Kafka. I would say that transmedia storytelling and immersive theatre are not related on paper. For example, one of the most important companies in immersive theatre is Punchdrunk, and I wouldn’t say that they are using transmedia storytelling. They are very perfectionist and detailed in making production spaces, but they don’t necessary create different stories in different media. They launched a book about The Drowned Man, but it is not a different story, it is a recreation, a memory of what you experienced there. They don’t conceive stories that start before or expand on different media, so I wouldn’t say that immersive theatre is necessarily transmedia storytelling, although transmedia storytelling can benefit a lot of immersive theatre as one of the channels used. In the end, they are different formats, but both transmedia and immersive make the audience the protagonist. They are very good allies that don’t necessary have to go together, but when they do, it is awesome.

AB: Do you think that in immersive theatre there are more elements of gamification, game mechanics?

BSO: Immersive theatre might and might not use game mechanics. I would compare what Secret Cinema and Punchdrunk do. Secret Cinema uses game mechanics much more than Punchdrunk does, even if it’s not very gamified, but there is this sense of competition that the actors put you in. They use very isolated dynamics that make you compete, and make you be part of isolated game mechanics, which I think in Punchdrunk they don’t necessarily do. You are a witness, but there are not so many game elements. I wonder if it is because of the barrier they create by using masks. You are a witness, you are not a character, you are really not an active role apart from choosing where you want to go.

AB: The boundaries of an immersive theatre are not really defined.

BSO: I think these components work together pretty well, but it is not compulsory that theatre has to have game mechanics or the other way around.

El proceso, de Kafka. Photo by Daniel Pérez.

AB: Can you lead me through your creative process?

BSO: Stroke114 got commissioned to create The Trial in a stage incubator program in Malaga. We thought this was an opportunity to tell the story of Joseph K. in an interactive way. Our premise was that everyone, any day, can become the subject of a Kafkaesque trial. What if what happened to Joseph K. happened to you? In the end, Joseph K. is prompted to carry on with his normal life while he is having a trial that overshadows everything, as he is contacted all the time. This is why we started thinking: how can we create this? How can we use transmedia storytelling to make the audience participate in a more active way and experience that themselves? This is how we started to create this setup of different initiatives and content on different platforms to generate the idea of the pervasiveness of the organization called ‘The Door Of The Law” (www.lapuertadelaley.com). We were collaborating with actors who would hand out subpoenas on the street. We were using newspapers and posters. We used networks like Tinder, Airbnb and a second-hand sales platform called Wallapop , but also organized an exhibition with visual artists and engaged nationally-known opinion-makers through personalized posted packages. All this was done with a very clear visual identity, but the analogical components were very important too. By using Conducttr, we could reach out to the engaged people based on previously collected data, personalized messages, and phone calls (which were sometimes were conducted at 2 a.m., as the court of Kafka’s novel would). The play itself is more self-contained, and no participative element was included. It is an experience based just on witnessing, but the day before the show audiences also receive a phone call, where they are told: “this is not the end, this has just started.” We had 12 show days in 3 weeks, performing from Wednesday to Saturday. In total, we had 900 audience members and we had a very good interaction rate: 250 interrogation situations through the website (which is a pretty high rate for an interactive project). Normally, when you create a transmedia project you have to calculate that 5-10 percent of the audience will be interactive, and that is a success already. All this was made from 25 000 Euros, from which we only spent about 10 percent for the transmedia experience because we used Conducttr.

AB: Can you tell me more about Conducttr?

BSO: Sometimes we work as transmedia consultants, but basically, it is a technology company, so we do have a software, a platform to create multiplatform experiences. The license for Conducttr is 500 dollars (for indie projects) per year to create all interactive components.

AB: When you get a new commission and you have this tool, what is the process for using that tool and personalizing it?

BSO: Personalizing is like creating a logic. For each client, we create a different logic. We know how to use Conducttr, and we can create a specific logic which is based on ‘triggers’, ‘conditions’ and ‘actions’. You define the triggers that Conducttr should listen to, and then you set up the conditions that should match the triggers: which person belongs to which group, or if a person is female, and then the action that will follow that event. Actions are things such as sending an e-mail, publishing content or making a phone call.

AB: Were you also participating in the development?

BSO: I created all the interactivity but I also had the team at Conducttr to help me at specific points, while creating the video-interrogation room for example. They were part of the creation of the logic as well.

El proceso, de Kafka. Photo by Daniel Pérez.

AB: Did you find that it was helpful for you to have a background in theatre in creating this project?

BSO: Transmedia storytelling is a kind of theatre in the sense that you have to keep the audience in mind. When you are a filmmaker or you create a video, you do not take into account what people are saying, but in this kind of narrative the audience response is embedded and it has an impact. That is exactly what is happening in theatre. This idea of liveness is present, as it is happening in real time. A sense of the rhythm and pacing of a piece: this is what I learned from theatre and what I brought to transmedia storytelling. I like to put as much of a physical component in my transmedia storytelling as possible because that really makes the connection. Even if it cannot reach all audience members, it really makes it feel real. It transcends the screen in the moment when screens are overpopulated with content. It makes the story relatable through the physicality. I think that is magic.

AB: How do you see theatre in 30 years?

BSO: I see theatre not calling itself theatre, in the sense of it becoming more open to being permutated into different experiences. I think we are going towards a stage experience where it is not about actors playing a role, but it is about the audience on the stage with the characters. We are going to see a tendency towards a lot of experiences not calling themselves theatre, but that are kind of scenic, stage experiences in which theatre is transformed into something else. I totally see immersive theatre as a big trend. Interactive experiences are a big trend, experiences in which the audience is participating much more and feeling the idea of experiential leisure. Millennials tend to place value much more in experiences than material goods. That is different from the past. They look for travelling and festivals. There is an opportunity to leverage that and to make theatre that isn’t stuck in the past, but that evolves and transposes itself into these experiences that will be theatre, but wouldn’t be called theatre anymore.

AB: How do you see new and immersive theatres? Are they actually changing the experience of the interactivity for the audience, or is it just the form changing? Are people feeling differently in interactive situations where immersive technologies are used?

BSO: We are just discovering a new language/grammar. The audience has to discover the grammar every time. It is not like when you go to the theatre and you know every time what’s going to happen: actors come out and then when they finish, they just bow, that is the grammar crafted through the centuries. There are rituals that we have evolved in the grammar. When there is a completely different media involved, every time the audience has to understand the grammar. It is a huge effort from them to understand, for example, what interaction means. In theatre you know you can’t talk loudly, but here that’s not true. This creates a sense of amusement. Should I or shouldn’t I be here? I think this is the magic. We are all illiterate in this aspect, we don’t know the grammar, and because of this everything is new. I also see the benefits when a certain grammar is established, and when we are all more used to this, we will be able to create more profound stories. Right now, when you mess around with interaction your story cannot really go very deep, so it is typical that these companies are choosing stories that we all know. Fairy tales, Shakespeare plays, stories we know and are comfortable with. They don’t play with the story, they play with the languages, the grammar. In the future when transmedia storytelling becomes more established, we will be more able to go beyond the familiar stories into something deeper and that explores this grammar a bit further.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ágnes Bakk.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.