MMK3 is the smallest of Frankfurt’s Museum für Moderne Kunst’s three buildings, and Hassan Khan’s exhibition Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said began here from outside the gallery. Applied to its windowed façade were two giant faces looking away from one another, fashioned from brightly colored, semi-transparent plastic. The faces told stories; they looked tired: exhausted, wearied by life. Above each head, spelled out in vinyl lettering, was the title of this exhibition (also, this work). Above one head the words face outward, towards the street; above the other, the words face inward, towards the gallery.

“A window is a platform, a stage, an entry point,” Khan writes in a short essay to accompany the exhibition. The text has been printed and stacked on a plinth in the vestibule between the inner and outer set of plate-glass doors at the gallery’s entrance. “The frame for a double portrait of power. It is, however, out of necessity, a disassembled double portrait. For how else can we tackle a judge who was a police officer and now hands out death sentences like candy?”[1] This text, which functions both as exhibition text and press release, takes the form of an imaginary, artist-led tour of the display. It is difficult to take in all at once. It outlines the historical contexts of each work and is a meandering, stream-of-consciousness affair that jumps from references to Philip K. Dick to the sixteenth century English composer and poet John Dowland. The specific passage quoted above relates this exhibition’s first work to the story of the Cairene judge who, in February this year, handed out the death sentence to 183 members of the Muslim Brotherhood in response to the killing of 16 policemen in the Egyptian town of Kardasa in August 2013.[2] A sound work leaks through the gaps of the inner set of doors and imposes upon the attention given over to the exhibition text.

A quick scan of the text makes us aware that the works that comprise this display are references to other things, though it’s unclear precisely what at first. Literature is the obvious reference (the title of both the exhibition and its first work is taken from a 1974 novel by Dick), but that doesn’t feel very important. It feels too academic, too detached. Hassan Khan often demonstrates a tendency to implicate the viewer in his works. “This white space is a stage (there’s the word again: “stage”) – a platform that highlights and draws out a set of material conditions and coldly inspects them,” Khan has written previously.[3] What is the self in this space? He goes on: “[t]he figure can be allowed to appear. The ground is the context… The subject is enframed, is charged with the concept of the self, of a persona performed.”[4] It is a concept that is easy enough to accept in theoretical terms but less so in practice.

Hassan Khan, “Taraban,” 2015. Live at Portikus, Frankfurt, 2015. Courtesy of the artist. Photographer: Helena Schlichti.

A week after Khan’s exhibition opened, he performed Taraban (2014) at Portikus, a Kunsthalle located on a small island on the River Main, a short walk from the center of Frankfurt. The artist has a growing relationship with the city. In addition to the exhibition Flow My Tears…, this performance was devised with a research-in-exhibition program that Portikus has developed with Städelschule, the art school where Khan has a guest professorship. Taraban is Khan’s own composition, and that is based on two songs from the early 1920s. The piece was meticulously put together in a recording studio as a multichannel mix by Khan alongside session musicians. The piece is then bounced as an eight-channel mix that Khan can then perform live (by reconstructing it and putting it together in relation to how he commonly works with sound and uses his other instrument, the feedback mixer). In Khan’s own words, “an important element of the work is how I work on the language of classical Arabic music to produce something that is authored and structurally different (not just texturally).”[5] With the aid of a computer and a giant mixing desk, Khan rearticulates the composition as a performance, treating the sound through a series of filters, processors, digital manipulations, synthesizers, feedback mixers, and live microphones.

Taraban is at once recorded, a live performance, and an improvisation, produced through a captivating process that creates a spellbinding sound. By subjugating these melodies to various filtering techniques, Khan ultimately created musical vortices. He returned to passages over and over until they became collections of moments arrested in time. These individual passages, these contained bars, become the subject of our attention, and our comprehension of these contained passages affected our comprehension of the piece as a whole. Indeed, a close listening of these repeated sequences transformed the overall melody from one that is concerned with the performative (that is, externalized) to one that is concerned with the construction of the self (that is, internalized).

Taraban itself is a system of interpretation as well as being evidence of a process of the artist’s creative – and thus subjective – thought. Rather than “art making,” perhaps the term “directing” is closer to what Khan attempts in his work. The works themselves are material through which to contemplate Khan’s thought processes and interpretive systems. They move us – the audience – into a position on-stage and we are left to ask the question of where meaning is created. The artist provides the material and the processes, and we come prepared with the paradoxical knowledge that exhibitions – particularly museum exhibitions – rely on a specific form of spectatorship, where we allow ourselves to become involved in a multi-layered, authorial narrative structure despite the fact that the cornerstone of analytical discourse is based on the deconstruction of narrative in order to reveal constructed power, hierarchy, and/or concealed ideology.

The physical presence of the audience in the exhibition Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said is acknowledged – applauded, even. Four speakers, on stands at face height, variously emit a rhythmic clapping. This work, Live Ammunition! (2015), is a four-channel audio installation; the one that could be heard leaking through the doors into the gallery’s inner vestibule. It is a hypnotic cycle of clapping, followed by the creeping of strings and electronics. In the exhibition text, Khan describes this sound as “the beat of the show.”[6] It is an austere presentation for a performance of great effect. Like in Taraban, Live Ammuntion! is Khan’s own composition, in which all elements are meticulously recorded in the studio with percussionists as clappers. The sounds are then put together to create the polyrhythms. As Khan explains it, the work is connected to another piece, Live Ammunition!! Music for Clapping, Strings and Electronics: “both rely on the same recording sessions but are constructed differently…what is important is that they have an authorial voice as well as an amount of labor that is actually creative labor (a form of writing if you will).”[7]

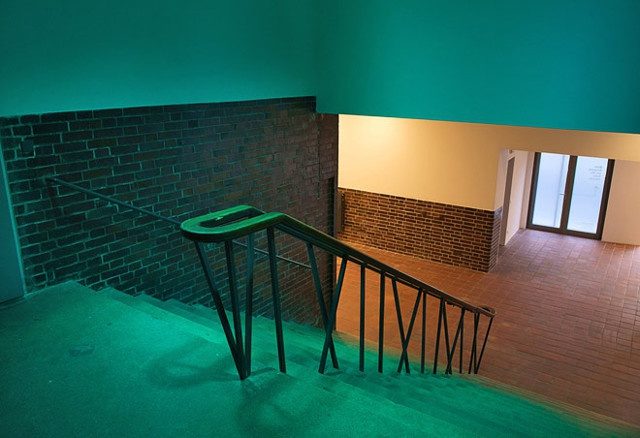

For more than a few minutes I stand transfixed before Live Ammunition!, an audience of the music, despite the fact that I know that I’m just looking at speakers. The clapping begins jarringly, the individual strikes jump from speaker-to-speaker and crescendo in both volume and intensity to ultimately create a dense wall of sound.[8] It’s a testament to the power of this piece that I don’t notice colored lights pulsating beside me, turning from red to yellow to blue to green. This is another work, LightShift (2015), installed over the staircase that leads from the entrance area to the gallery’s main atrium. Innocuously – frustratingly – it pulls me away from the music and the reverie of the display so far. I feel the lights should infiltrate my senses, like the music had done, and lead me up the stairs. It’s a pivotal point in the exhibition, LightShift acts like a fulcrum in this building, bridging the exhibition’s pounding opening to the big reveal of its melody-to-come. Instead, I’m left aware of my surroundings. The shifting lights have brought attention to the structure of the show (even more so because the gallery have a ticket inspector sat at the top of the stairs). The entire arrangement of this piece needlessly interrupts the exhibition’s hitherto carefully constructed logic. You know how when you were younger radio DJs would talk through the opening of the songs on their playlist, specifically so you couldn’t tape it entirely? Here I am, waiting to explore the rest of the show and I’m forced to take a moment of pause. But perhaps this is a useful time to reflect upon what I’ve seen, what I’m seeing now, and what I anticipate seeing.

The event invokes a rupture, necessarily. It would be erratic to spend time in this essay going back to terminologies already well-established in contemporary philosophy (that’s much less its purpose), but let’s retain the following:

Let’s agree to the term first inconsistent multiplicity and the second consistent multiplicity.

A situation (which means a structured presentation) is, relative to the same terms…inconsistent and consistent… Structure is both what obliges us to consider, via retroaction, that presentation is a multiple (inconsistent) and what authorizes us, via anticipation, to compose the terms of presentation as units of a multiple (consistent). It is clearly recognizable that this distribution of obligation and authorization makes the one – which is not – into a law. It is the same thing to say of the one that it is not, and to say that the one is a law of the multiple, in the double sense of being what constrains the multiple to manifest itself as such, and what rules its structured composition…[9]

This assertion underpins the rationale of this text. An inconsistent multiplicity is comprised of both void and excess. It is enframed within a structure of a dominating ideology. We can move on from this to come to a series of working conclusions around specific theories of the event[10] in relation to temporal locations. Bertrand Russell was the first to explain how objects occupy four-dimensional space.[11] From this vantage point, we can extend the question of the place of the person in the exhibition, to the question of the place of the object in the exhibition. Are the objects “coherent” (that is, fixed), on the one hand, or on the other, perhaps routinely being readdressed in interactions with the exhibition visitors? Regardless, to purely base an understanding of the exhibition on individuated experience here seems like an ontological fallacy.[12] We can argue therefore that the event-as-interruption precedes a Truth, but that that knowledge is unstable.

Hassan Khan, Abstract Music, 2015. Stacked glass. Courtesy Hassan Khan, MMK/Frankfurt. Photographer: Axel Schneider.

The centerpiece of this exhibition is a work titled Abstract Music (2015). It is a beautiful and captivating piece that gleams in the eye as it emerges into sight on the upper level. MMK 3 is a chapel-shaped gallery, which tends to give the works it houses an imperious quality. Abstract Music isn’t the only artwork in the room but it’s a show-stopping piece that rises to the grandness of its surroundings. The title seems off-kilter, the work is a cluster of 13 glass sculptures, ovoids of varying sizes stacked on top of one another, each column is raised from the ground on its own individual dais and spotlit dramatically from above. Beyond this work, by the end wall, rear-projected onto a 21-inch screen is the only work not made specifically for this show, Studies for Structuralist Film no.2 (2013). Set off to the side of the room, the third work in this main space feels incongruous, and creates an odd sense of balance to the display. The Double Face of Power (2015), a title that recalls the exhibition’s first work, is a three-panel wooden dressing screen or room divider. Each panel shows a different emblem comprised of white lines carved into a grey, green, and red colored background.

The exhibition, like any other, presents the appearance of a composed identity. Live Ammunition! continues to gradually get louder and louder, and once again begins to cloud the entire gallery space, we become aware that the effectiveness of this display is contingent on many irregular factors. If we can talk about curating as a “practice” that utilizes an evolved form of relational techniques (in one given terminology, of course relational curating has its precedents) then we have a phrasebook of concepts that relate to how artworks can activate a situation. Did you realize that the viewer can walk around, can get a 360° view of every artwork? In the case of LightShift, for example, we can even walk through the artwork. This kind of viewership may be somewhat standard for sculpture raised on a plinth, a work like Abstract Music (the most “traditional” fine art work in this display), but if we return to the beginning and replay each work: the mural isn’t fixed to a wall, but to a window. The speakers aren’t bracketed into corners, but stand in a line. The film is rear-projected and we can literally walk behind the screen.[13] The rear side of the room divider is set towards the wall, but we can see around it. Frustratingly, only the front side is decorated. I feel like we’ve been allowed to see behind the scenes and it’s revealed that this exhibition, despite its arresting qualities, is merely a set, a soundstage for a performance that we’ve somehow become a part of. A sober reality emerges as I begin to think about how I’ve been required to perform the role of the audience as much as the artworks have been made to perform their roles as material gesture.

Hassan Khan, LightShift, 2015. Courtesy Hassan Khan, MMK/Frankfurt. Photographer: Axel Schneider.

The concept of “inconsistent multiplicities” (as interpreted between Cantor and Badiou) has similar outcomes to the term that Khan uses in his exhibition text, “bracketing transformations,” that moment of clarity when an audience member is “between” objecthood.[14] These artworks provide the reality of the show, but they are not objects for their own sake, designed to present a narrative or a point of view. The works in this exhibition defy their setting. Situations have two faces: one that points towards a regime of consistent multiplicities and that are structured by operating procedures; the other that marks the excess of “pure” multiplicity. What we expect and what appears to be ultimately evades determining itself by virtue of itself. In Badiou’s definitions, the situation is not important but Truth appears once an agent belongs within a situation. Truth is connected to agency and intervention. As an audience we can witness such intervention in a work like Taraban, where the lifespan of an object (in this case, the pre-recorded concert piece) is stretched, protracted, unrolled, and magnified until it becomes something new, yet still recognizable. For Khan, that act of agency is where “transformation” occurs. It’s a difficult place, somewhere between absolute void and complete excess. “The performances of belonging promise but never deliver… Thus, negotiation is key,”[15] writes Khan. But that place of transformation – of Truth and knowledge – would not emerge were it not for the performances that these artworks undertake – it is irreducible to what came before and will become necessary in describing what comes next.

Perhaps it is easier to explore these concepts through Khan’s music-based works, which are integral to his practice overall, because even its improvised moments are based on a set of rules and systems. Analyzing success in the visual arts is an inexact process (art sales notwithstanding). Criticality is often often judged on the dissemination, longevity, and publicness of responses to an exhibition or artwork. But performance is always contingent on the public that it engages directly, the right shift in tempo can cause a ripple of sensation across your live audience. Very simply, as Plato suggests, we know when belief is true because we can generally provide a demonstration of that belief. Yet, of course, knowledge is variable, among various aspects, including personal experience. We may reject the full extents of Badiou’s assertion that “[t]he rule of knowledge is always a criterion of exact nomination”[16] unless we also accept that statements, or propositions to any given statement, can only “describe” any given state of affairs.[17] Therefore, in writing this essay on Hassan Khan’s exhibition Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said, I have removed myself one step further, first from audience, then to participant, and now to respondent.

An exhibition is the conscious act of creating a structure for communication,[18] and are inherently critical productions. Structure is key, particularly when addressing curating as a “practice” because the term “practice” suggests an ongoing process. Performances are finite, like Truth there is the implication of boundaries and the knowledge of an end to come. My presence in this exhibition created a necessary rupture in its logic. Necessary because my presence enacted a moment where criticality performed itself. The artworks on display here articulate a situation that becomes, as Yasmeen Siddiqui has written on Khan, a “new paradigm for human encounter…an idea from multiple standpoints.”[19] Even if we wanted to, it would be erroneous to discuss this exhibition solely within the terminologies of visual art. This exhibition is a loose assemblage of thinly-related works and, as such, its structure is less moderated than an exhibition’s generally would be. Just as Khan’s 2003 work 17 and in AUC was described as “appearing to tackle autobiography head-on…[it] was in fact an exercise in the technology of communication,”[20] so is this exhibition concerned with communication. Khan has stated his interest in “modulation…For example, a short story based on a distant memory with a long musical interlude is structured as two experiences. A text and then a concert and then a text. When you return to the text it has completely changed because of the experience of the music.”[21] Khan provides the beat of the show. The performance is up to us.

Watch Hassan Khan’s performance 17 and in AUC on Ibraaz projects.

This article was first published on www.ibraaz.org. Reposted with permission of the publisher. Read the original article.

Notes:

[1] The full text can be found here: http://mmk-frankfurt.de/en/exhibitions/review/2015/.

[2] O. Fahmy, ‘Egypt court sentences 183 Muslim Brotherhood supporters to death,’ Reuters, 2 February 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/02/02/us-egypt-brotherhood-court-idUSKBN0L60VK20150202.

[3] H. Khan, ‘RANT,’ e-flux 2, 2009, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/rant/.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Details on the performance of Taraban at Portikus, Frankfurt am Main, on 5 February 2015 can be found here: http://www.portikus.de/1490.html?&L=1.

[6] The full text can be found here: http://mmk-frankfurt.de/en/exhibitions/review/2015/.

[7] Hassan Khan via email, 04 November, 2015.

[8] The Wall of Sound, as developed by music producer Phil Spector in the 1960s, was created by having both acoustic and electronic instrument playing the same parts in unison and then adding musical accompaniments played by orchestra-sized bands. The idea was to create a sound specifically for the audio limitations of jukeboxes.

[9] A. Badiou, Being and Event (London: Continuum, 2007), p.54.

[10] The relating of the event to the ‘consistent’ and ‘inconsistent multiplicities’ appears first in Badiou’s Being and Event, however the latter concepts are originally taken from the mathematical philosophy of Georg Cantor. A brief explanation of Cantor’s Paradox can be found here: Weisstein, Eric W. ‘Cantor’s Paradox.’ From MathWorld A Wolfram Web Resource. http://mathworld.wolfram.com/CantorsParadox.html, along with further references to the concept.

[11] B. Russell, The Analysis of Matter (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co, 1927).

[12] Further definitions of the role of object in four-dimensional space can be found in N. Goodman, The Structure of Appearances (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1951); and L.B Lombard, Events: A Metaphysical Study (London: Routledge, 1986), among many others, including works by Willard Van Orman Quine, Roland Stout, John Lemmon, and Anthony Galton.

[13] I’m trying desperately to avoid referencing The Wizard of Oz.

[14] My reference for a definition of objecthood comes from M. Fried, ‘Art and Objecthood,’ Artforum, Summer 1967.

[15] Khan, op cit.

[16] Badiou, op cit.

[17] Paraphrased from J.L. Austin, How to Do Things with Words (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1962), p.2.

[18] This is a common assertion though not necessarily always the case. My point of reference here includes a number of texts, but that begin with the idea of the contemporary functions of the museum as highlighted in, including, L. Alloway and J. Coplan, ‘Talking with William Rubin: The Museum Concept is Not Infinitely Expandable,’ Artforum 13.2 (1974), or Hans Ulrich Obrist’s interview with Jean Leering from H.U. Obrist, A Brief History of Curating (Zurich: jrp | ringier, 2008).

[19] Y. Siddiqui, ‘The Multiple Standpoints of Hassan Khan,’ Hyperallergic, 9 July 2014, http://hyperallergic.com/136655/the-multiple-standpoints-of-hassan-khan/.

[20] J. Griffin, ‘Hassan Khan,’ Frieze 101, September 2006.

[21] Siddiqui, op cit.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ajay Hothi.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.