On March 20 2018, VaChina, a London-based Chinese feminist network, staged its first full drama show Our Vagina, Ourselves (阴道之道), the Chinese version of Vagina Monologues, in the lecture theatre of SOAS, London. Around 100 people filled the lecture theatre, with some enthusiasts having to sit on the floor to watch the Chinese version of Vagina Monologues in Chinese languages played by international performers (plural because the play’s conversations were also performed in dialects other than Mandarin Chinese).

On March 5 2017 in New York, Our Vagina, Ourselves was performed by a group of New York-based Chinese feminist network that also initiated and published the petition against sex harassment in China among Chinese overseas students as part of Chinese #MeToo. Both shows are a continuation of the Vagina Monologues-influenced English-language feminist work that began fifteen years ago in China and is now, finally, traveling abroad and being performed in the Chinese language.

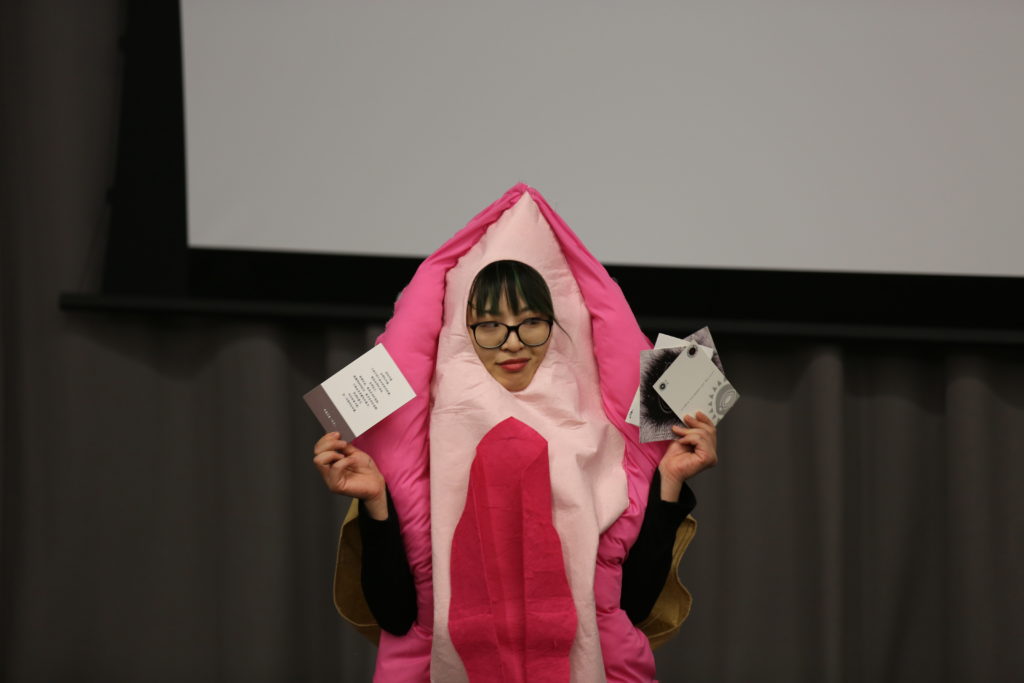

Our Vagina, Ourselves (阴道之道) at SOAS University of London. Source: VaChina; Photo Credits: Junchi Deng

However, between two shows in London and New York which fell around the International Women’s Day on March 8, the Chinese Social Media Weibo suspended FeministVoices (女权之声) and then completely banned the group, which remains the largest independent feminist media in China with 181,019 followers. To support them, audience and participants of Our Vagina, Ourselves in London were asked by volunteers to take photos outside the registration area with pre-made FeministVoices Weibo and Instagram cardboards.

Our Vagina, Ourselves (阴道之道) at SOAS University of London. Source: VaChina; Photo Credits: Junchi Deng

The script of Our Vagina, Ourselves was written by the Beijing-based feminist group BCome, a drama-focused group established in 2012 with support from Beijing based NGOs Media Monitor for Women Network (妇女传媒检测网络) and YiYuanGongShe (一元公社). While the latter is one of the pioneer NGOs that covers LGBTQ issues in China, the former is known to most as the FeministVoices.

As feminist academic Rong Weiyi (荣维毅) has summarized in her online article, the traveling of Vagina Monologues is crucial to the development of young female activist groups across China. In 2001, Vagina Monologues had its first show in English in Nanjing at the Johns Hopkins University-Nanjing University Center for Chinese and American Studies. In 2003, a renowned feminist activist academic Ai Xiaoming (艾晓明) based at Sun Yat-sen University partially localized the plot and arranged the first show in the Chinese language in Guangzhou Museum of Art.

Our Vagina, Ourselves (阴道之道) at SOAS University of London. Source: VaChina; Photo Credits: Junchi Deng

Within a few years, different versions of Chinese Vagina Monologues have spread to various regions in China, spreading gender awareness and the spirit of civil participation among participants and audiences (see Fan Popo’s documentary The VaChina Monologues). Entire original scripts based on interviews with hundreds of Chinese women were created in different regions of China. For instance, in 2012, Cloudy Vagina (阴dao多云) was organized by Shanghai Beaver Club in Shanghai. In 2013, stage play For Vagina’s Sake (将阴道独白到底) was arranged, again by scholars and students at Sun Yat-sen University, in urban and rural areas in Guangdong province with a sharp critique of the society privileging sons over daughters. In the same year, BCome also showed their drama on the stages of NGOs (including LGBTQ-focused NGO Common Language), theatres, universities (most remarkably and controversially at Beijing Foreign Studies University) and even the Beijing Metro in the form of a flash mob.

Our Vagina, Ourselves (阴道之道) at SOAS University of London. Source: VaChina; Photo Credits: Junchi Deng

Escaping the difficulties and risks of organizing protests, art has become the favored, and, likely, safer form of bottom-up resistance and civic appeal. The drama participants are also behind campaigns to encourage the general public to reflect or at least become aware of discrimination against women and sexual minorities. They have staged various art performances and feminist trek to combat sexual violence. They also organized the first ever LGBT music festival in mainland China. At the same time, we witness a continuation of pluralization of Chinese Vagina Monologues. In 2016, Vagina Project (阴道说) was established in Beijing with another group of university students and graduates. Within a year, their script was adopted by a few other organizations based in 8 different cities.

Our Vagina, Ourselves (阴道之道) at SOAS University of London. Source: VaChina; Photo Credits: Junchi Deng

After the show in London, I talked with several audience members about what they found most striking about the show. One of them said to me: “it is perhaps the use of Chinese Language.” After five years of studying overseas, she was finally able to experience feminist solidarity in her mother tongue. Feminism in China will not end with the ban of #MetooinChina hashtags, nor will it end with suspension and blocking of feminists’ social media accounts. In fact, these and similar measures often have unintended social impacts. Anthropologist Vanessa Fong has pointed out that the one-child policy has unintentionally cultivated feminism among the one-child cohort and their parents alike (see her book Only Hope). As long as feminism continues to spread and resonate with more and more Chinese, there is always hope.

Our Vagina, Ourselves will be performed again on 13 June 2018 at the University of Oxford.

Ling Tang is a Junior Research Associate at the International Gender Studies Centre of the University of Oxford.

This article originally appeared in China Policy Institute Analysis, the online journal of the China Policy Institute at the University of Nottingham, UK. Reproduced with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Ling Tang.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.