South America’s trauma in the second half of the twentieth century can be summed up by one phrase: The Disappeared. Whether in Argentina or Chile or anywhere else, the victims of military dictatorships multiplied in the 1970s and 1980s. Aptly enough, New York playwright Caridad Svich’s excellent adaptation of Isabel Allende’s 1982 modern classic begins with one of the disappeared, student radical Alba, who has been arrested after a military coup in an unspecified country that seems very like Chile under General Augusto Pinochet. While she is being tortured in a scene which powerfully evokes not only her agony but that of a whole generation of 1970s South American leftists, she remembers and narrates her family history.

Allende’s The House of the Spirits began as a letter to her dying grandfather, written from exile after she fled Chile in the wake of Pinochet’s coup, a military takeover which cost the life of Salvador Allende, the freely elected socialist president of Chile and her father’s cousin. The novel is a hugely ambitious family epic which mixes naturalism and magic realism to tell the story of four generations of the del Valle and Trueba families, with a particular focus on the women. Svich’s stage version, which won the 2011 American Theatre Critics Association Prize, is written with enormous confidence, concision and theatrical skill. Although inevitably simplified, it conveys much of the original’s emotional force and its spirit.

As narrated by the imprisoned Alba, the story begins with her grandmother, Clara, as a child. Looked after by their bourgeois mother Nivea del Valle, Clara and her older sister Rosa live an enchanted life. When Rosa dies mysteriously, an event that Clara — who is psychic — has predicted, her devastated fiancé Esteban Trueba, who works as a miner, turns his attention to improving his family’s derelict country estate, The Three Marias. After managing this property for several years, he returns and marries Clara, and the couple has a daughter, Blanca. When she is a teenager she falls in love with Pedro, a young radical. These relationships are complicated by the fact that Esteban has raped so many local women that the estate is littered with his children.

Eventually, Blanca gives birth to Alba, and she continues the revolutionary feeling in the family, whose women are notably more radical than the men. The epic canvas, which includes constant movement between city and countryside, and features at one point a terrible earthquake, is effectively and economically sketched out by Svich, who concentrates on the emotional truth of the family relationships, including Clara’s relationship with Férula, Estaban’s sister. Other episodes, such as Alba’s discovery of Clara’s diary and Estaban’s marrying Blanca to the French count Jean de Satigny, are well integrated into the stage narrative, which also features the family’s delightful dog, Barrabás. At the same time, the magic realist elements are kept under strict control, merging most poignantly at the end of the show.

The House of the Spirits, performed in a bilingual production directed by Paula Paz, is a very spirited evening, but also one with its fair share of irony. For a play about four generations of women, all of whom overcome hardships, it is surely ironic that the most complex and contradictory character is Esteban. But although he dominates the story, he is not a very attractive person. Not only does he visit prostitutes, symbolized by the character called Tránsito, but he also rapes the peasant women, such as Pancha. When the socialist government is legally elected, he denounces any radical as a Communist and helps the generals to organize a coup d’état. Not very nice. But while we may cry out for justice against this macho man’s crimes, neither Allende nor Svich will answer. In fact, in the end, this story shows how family wins over politics. Men get away with murder. So the story both expresses a desire for change and subverts it.

Despite this rather reactionary message, which is a bit odd for a feminist play, the story is absorbing in its emotional perceptiveness and sensual reality. Paz’s production has a fine pace and the narrative is clear and compelling, with designer Alejandro Andújar’s backcloth featuring an old family photograph and video by Enrique Munoz, which spills reams of words across the landscapes evoked by the text. A lot of the acting is well-focused and energetic, although the inclusive nature of the cast — who all come from a variety of Spanish-speaking countries — means that there is a slight unevenness of tone. Some actors have more passion than others, some are louder than others.

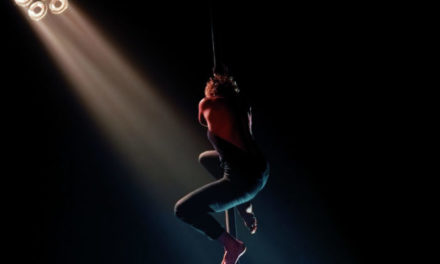

Nevertheless, there is much to enjoy here. Raul Fernandez dominates the action as Esteban, even when he becomes aged and regretful; he strongly conveys not only his character’s restless forcefulness and toxic masculinity — the rape scene is genuinely disturbing — but also some of his charm and his determination to improve his land. Pia Laborde-Noguez’s Alba acts as a narrator and guides us through the story’s labyrinth, while Constanza Ruff’s Clara embodies the magic and the pain of the central character. There’s good work also from Vanessa Calderón as Rosa and Blanca, Alejandra Costa (Tránsito), Daniela Cristo (Pancha) and Elena Saenz (Férula), together with the rest of the 12-strong cast. This is an adaptation that is full of feeling and rich in ideas and complexities.

The House of the Spirits is at the Cervantes Theatre until 11 December.

This article was originally posted at Sierz.co.uk and has been reposted with permission. To read the original article, click here.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Aleks Sierz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.