Since I will be recalling many other voices, I will start, somewhat pretentiously, with my own, in order to create a field for further narration. My adventure with Krystian Lupa’s Factory 2 began a few years ago, when Grzegorz Niziołek and I were arranging the syllabus for a university course called ‘Theatre After 1989’. When choosing analytical material for a block of classes centered on the subject of contemporary performative acting entitled ‘Actor/Performer’, we decided to feature Factory 2, among other productions. I would add that it was at the time quite an obvious choice, supported by extensive journalistic and academic literature. Our syllabus included a section of Beata Guczalska’s book Aktorstwo polskie. Generacje [Polish Acting: Generations], in which she writes:

It would seem that in this case the rehearsal process was the actual work of art, conceived as a journey of a certain community. What comes at the end, namely the performance, occurs as a fluid, but not necessarily essential, consequence of the previous activity. Krystian Lupa was the guide on this journey, but the actors contributed as much, especially the young ones.1

Guczalska shifts the center of gravity from the stage effect onto the work process, and from the model of director’s theatre (Regietheater) to an ensemble one. She also draws attention to the revolutionary nature of this venture in terms of the approach to acting: ‘The boundaries between the role and private life, between the truth of stage experience and overt pretending, between theatre and performance, have been crossed so radically that there is no chance of returning to rigid divisions’.2 Similar narratives return regularly. In 2017 Maria Anna Potocka wrote that in Factory 2 ‘actors […] ceased to be actors […] they were given the freedom to improvise. The director gave them freedom to create their chosen character […]. In this way a theatrical piece came into being which in a sense created itself [in relation] to the place where one can be free, liberated and creative’.3 In 2018 Maryla Zielińska entitled her text on Anna Karasińska’s theatre style Factory 3, and began by eloquently recalling the legend of Lupa’s show: ‘In 2008, in Kraków’s Stary Theatre, Krystian Lupa recreated Andy Warhol’s silver Factory. The imitation of Warhol’s studio was conceived as personal space for the company performing Factory 2, a kind of an enclave guaranteeing the participants’ safety’.4 The production, subtitled ‘a collective fantasy inspired by the works of Andy Warhol’, became to a large extent a turning point in contemporary reflection on the subject of actorly freedom, creativity and empowerment, as well as collaboration in which the director renounces a part of the ‘authority’ assigned to them in favor of other artists creating the show. Apart from academic publications, we also included in the syllabus for the course the interviews printed in Didaskalia 845 that were conducted by Julia Kluzowicz with Katarzyna Warnke, Adam Nawojczyk, Zbigniew Kaleta, Krzysztof Zawadzki and Piotr Skiba immediately following the premiere. Reading them several years after the premiere had a surprisingly sobering effect on me. This document turned out to be crucial for me as well as many students. Under its influence, from one year to the next, each time with a different group, conversations on this production became increasingly critical both of the myth of Factory 2 and of Lupa’s work methods. It came to the point that in recent years we have recalled this ‘myth’ only to dismantle it step by step, pointing to elements of evident manipulation on the part of the director. The creative freedom and empowerment of the actors were put into question. Questions were asked as to what exactly the meaning of the performative dimension of their stage creations was in such a situation. Is the performative condition possible without empowerment?6 Is empowerment possible in conditions of manipulation? While investigating this matter, I decided to supplement the archive with further conversations, with Małgorzata Hajewska, Marta Ojrzyńska and the dramaturge Iga Gańczarczyk.7 Currently I am straddling a researcher’s perspective – cool, critical, distanced – and the perspective of the process participants. Neither do I usurp the right to say ‘how it really happened’. I want rather to report my observations, conversations and doubts, while at the same time putting forward certain theses regarding the direction of research on contemporary acting. Having said that, I am aware that I also am performing here a certain manipulation of the gathered material, although of course that is not my intention.

Rehearsals for Factory 2 lasted about fourteen months. For that time, the rehearsal studio at the Chamber Stage of the Stary Theatre was given to the ensemble, and after a while it was repainted in silver, just like Warhol’s Factory. The actors were released from work on other productions. The initial period comprised joint exploration of the source material. For four months the ensemble watched Warhol’s films, learned the biographies of the artists involved in the Factory, and improvised. Katarzyna Warnke described the period as ‘summer day camp with Warhol’.8 At that time the first screen tests were recorded: individual acting sessions in front of the camera on the subject of ‘My fucking me’ and ‘My body’, as well as improvised sex scenes performed in duets. The screen tests were then viewed and discussed by the entire group, numbering a dozen or more. Subsequently the actors were asked by Lupa to write letters with the names of the characters they would like to play, the characters they would rather not play, and the characters that according to them Lupa should assign them. The final decisions were made by the director. Once the roles were cast, the work consisted for the most part of improvisations, often inspired by Warhol’s films. The entire process was recorded on camera. The final script, finished just before the premiere, was written by Lupa, but the scenes were discussed and modified under the influence of suggestions by the actors.9 Some of the scenes were a condensed record of improvisations; others contained dialogues from Warhol’s movies. It was these elements of the work that formed the basis of the narrative about the freedom of actors and the performative dimension of their creativity. However, these elements also prove the most problematic in interviews.

It can be assumed that the process began even before the rehearsals started. Lupa played out the issue of completing the cast by using rumours, while at the same time wielding the power to make decisions. This concerned mainly the young actresses, for whom being cast in a show directed by Lupa constituted a special privilege and opportunity. For unknown reasons, Lupa delayed the completion of the casting process. At some point, having already informed Mikołaj Grabowski, artistic director of the Stary Theatre at the time, but before announcing the final cast list, he changed his mind.10 This led to a situation in which several people first learned that they would be involved in Factory 2, and then that the director had decided not to involve them after all. Warnke speaks about this: ‘I had unofficial news that I was cast, but Krystian [Lupa] would evade me. Because of Factory I had to give up on being involved in Jan Klata’s Oresteia, and once I had given up on that, it turned out that Krystian would probably not cast me in his show after all’.11 Marta Ojrzyńska found herself in a similar situation. The actresses adopted different strategies. Warnke called Lupa, met with him, asked about her participation in the show, and immediately joined the cast.12 Ojrzyńska, in turn, decided to go to India for a scholarship. Only after she returned and learned that Iwona Buła had quit the cast did she call the director and was eventually also invited to participate in the show. It could be said that the actresses had to take responsibility for their involvement in the production and to show determination. On the other hand, it is obvious that the distribution of power and authority between them and Lupa was extremely unequal: two young actresses who had just graduated from drama school versus a great Polish director, their recent professor at the National Academy of Theatre Arts, working with whom, as Ojrzyńska put it, was ‘a dream come true’. We can assume that many actors were rejected despite having shown similar initiative. Lupa finally admitted in a conversation with Warnke that the situation was a strategy aimed at ‘mounting up tension before the start of work’.13 This process indeed paid off. It can be surmised that the people who joined the ensemble in this way were more strongly motivated. ‘Since I’m cast in this show, I want to take risks,’ says Ojrzyńska. The actress joined the ensemble after four months, which from a certain perspective gave her distance to the project and made her curious about everything at a point when most of the ensemble had begun to grow tired of the prolonged research and directionless improvisations: ‘I entered it with a completely different energy, unburdened by the baggage of screen tests, parties, interdependencies, free from the toxic relationships between the characters.’14 On the other hand, she was perceived as a ‘foreign element’. As Adam Nawojczyk notes, ‘The real situation of a young actress trying to find her place in a close-knit group of actors was in a way transferred into the show’.15 Ojrzyńska admits that she was not welcomed along the lines of ‘It’s great that you’re here!’ As she comments on her relations with her stage partners in the improvisation from the third part of the show:

It all played out between Aśka [Joanna Drozda], Gosia [Małgorzata Zawadzka] and me. They weren’t happy that I entered their scene – that much was clear. I think the actresses as characters […] might have been jealous of me. Imagine that suddenly a girl joins the group – a young one, the youngest of them, similarly talented, insolent, brave, Andy adores her […]. This in itself provokes emotions. Lines were uttered: “brat”, “smartass”…. “She didn’t even have a screen test, and now she’s going to be in the show.” It’s quite typical for this profession that people are jealous of those who are younger and more beautiful. What was private permeated what was professional and immediately transferred itself onto the stage. The question is to what extent it was arranged.

It is worth noting that Drozda and Zawadzka had a sex scene together before Ojrzyńska arrived:

They had it all worked out, they got on well with one another. I disrupted it. I think this also was a deliberate measure on Lupa’s part. And I won’t even tell you what went on in the ladies’ dressing rooms, as it would only be a cheap stunt. Various situations, you know. Things happened. But I perceived that too as games between the characters, not personal ones.16

This permeation of the professional and private spheres was played out by Lupa on many levels. The initial research period, when the direction of work was not specified, served this purpose as well. The way Lupa commented on Warhol’s films generated impressions about his expectations towards the actors of the Stary Theatre, expectations which in fact they objected to. They did not know whether they were supposed to improvise as characters, or private people. They rebelled against the way Lupa showed appreciation of the unconscious creativity of Warhol’s actors, which was frequently stimulated by drugs. They were also troubled by the tragic life stories of Warhol’s ‘stars’. The situation was so uncertain for them that they were afraid of simply translating the predicament of Warhol’s actors onto their own. According to Iga Gańczarczyk, the dispute between Małgorzata Hajewska, Adam Nawojczyk, Krystian Lupa and Piotr Skiba was fundamental here, in the course of which the phrase was uttered that Warhol’s actors discover something without being conscious of it. To this Lupa replied: ‘The fuck you need consciousness for?’ Contrary to these intentions, rehearsals affected the level of self-awareness of at least some actors. Hajewska puts it this way:

I was aware that I was entering an adventure without fully realizing the risk I was taking. It wasn’t about whether the show would succeed or not, but as what people we would leave this adventure […]. We watched Warhol’s films for months and in them his stars, who were at the same time his victims. […] You realize you find yourself in a similar melting pot. […] You realize that you’re watching others, but you yourself are in a similar situation. That’s always true, in any job, but you only become conscious of it now.

On the other hand, Lupa appeared to extinguish any conceptual approach to exercises and, for instance, criticized screen tests in which more formal and deliberate proposals were offered, whereas he showed appreciation for unconscious behavior performed in a state of specific intoxication.17 In his show, the drug that was to extract the content hidden in the unconscious was, according to him, improvisation. Lupa writes in the production program that it is ‘some mysterious sense, it is a new kind of life, or a new drug, or a new delight – or a new creative mystery the aim of which is transforming and developing personality […]. Extracting treasures hidden in the depths into the light of day of the camera footage’.18 But we may suspect that improvisations were not the only stimulants leading to the achievement of intoxication in the process of work on Factory 2. And here we come to a risky topic: the presence and significance of alcohol and other stimulants in the Factory 2 creation process. Hajewska says: ‘It was the point at which I stopped drinking alcohol. Privately I worked on not thinking about it at all; on the other hand, day after day, for a few months I practiced total intoxication. Alcohol was present in this process.’ We must bear in mind that the rehearsal process was spread out so much that it was difficult to set a rigid boundary between rehearsal time and time-off. The first stage of work was accompanied, for instance, by parties, both at the theatre and outside the premises. One of them was ‘Warhol’s birthday’. I admit that while watching the footage from the rehearsal studio,19seeing bottles and mugs in the frame and observing the behavior of the participants, it is very hard for me to believe that improvisation was indeed the only intoxicant. We can have doubts as to the state of some actors during the recording of screen tests as well. These doubts are reinforced by the words of Iwona Budner uttered during a conversation with the actors at the conference ‘Krystian Lupa – artysta i pedagog’ [‘Krystian Lupa: Artist and Educator’] held at the National Academy of Theatre Arts in Kraków (on 6 December 2018), who confirmed that her improvisation with Bogdan Brzyski and Krzysztof Zawadzki was stimulated by alcohol deliberately drunk beforehand. The idea and creation process of screen tests also appears problematic. On the surface it seems like nothing much: an actor records a monologue in front of the camera. However, the significance Lupa attributed to these recordings complicates such a simple description. In an interview by Łukasz Maciejewski, the director states that Warhol’s Factory was about extracting ‘authentic personality’. He defines it in a highly essential and enigmatic way as something that ‘very rarely comes to the fore’, which is why, as he concludes, ‘most people end their life in blissful or severe ignorance of their own personality’.20‘My fucking me’ exercises were one of the ways of reaching the actors’ personality and stripping them of actorly falsehood. Lupa describes the atmosphere of their creation in the following way:

Everybody came to the screen tests, the whole ensemble. We circled around this experiment together…. Someone would sit inside with camera-vampires and their fucking “I”, while the rest of the group – or rather horde, or herd – would gather behind the door as if in front of a mysterious shamanistic rite. Those who participated in the self-audition, in turn, would leave each session with three cameras as if they had been asphyxiated, drugged.21

I will admit that for me this juxtaposition of essential definition of personality with a description of being cornered – doubly so, by cameras and by the ensemble compared to an animal herd – sounds disturbingly oppressive. My impression is confirmed by Warnke, who says: ‘It was accompanied by huge emotions. We were afraid it would turn out that we had no personality’.22 It is also worth adding, as the actors said during the aforementioned conference, that Lupa claimed that he gave each of them a different task, which is why he forbade them to disclose to the others the trigger theme of their screen test. And even though the regulations created around the screen tests assumed a great deal of freedom23, it was Lupa who judged whether a screen test was successful, and the measure of success was the degree of his interest. ‘Krystian [Lupa] wanted to draw closer to the limit, wanted something intimate to be shared. And he triggered a suspicion in us: What were we to interest you with, Krystian? Who did we have to be? … The challenge “be interesting” was terrifying’.24 Especially as some of the actors, like Hajewska, who approached the task conceptually and decided, among other things, to photograph the camera, were criticized for not taking risks.25 And that was the main thing that Lupa evaluated, which personality was real and interesting, and which was not.

The constant presence of the camera in rehearsals also stimulated tension. Most of the actors talk about it as a tool of control and oppression. Zbigniew Kaleta even states, ‘The thing with the camera is most strange. It’s a topic for a psychologist, perhaps even a psychiatrist. […] The camera is someone who looks at me. Its eye is cold and artificial, but still it looks on and I’m constantly aware that I’m being watched’.26 However, the anger resulting from this situation was not focused directly on Lupa, but on the two young dramaturges operating the cameras, Iga Gańczarczyk and Magda Stojowska: ‘We felt a lot of hostility on the part of the actors towards us, because of the cameras. Some people wouldn’t talk to us at all. They knew that we were shooting on Lupa’s orders, but at the same time they could not take it out on him, so they would direct all this aggression and anger at us.’ Lupa employed a similar device of redirecting emotions in the case of the script. Some actors were anxious that after several months of work there was still no definite text material. Iga Gańczarczyk says:

Magda and I prepared a document, what you might call a draft of the script, based on our research and composed of books and excerpts from Lupa’s journals. It ended up completely scrapped. […] There was a rehearsal Lupa brought it to. He began reading the script in the presence of the actors, page by page, giving the actors the appearance that something existed, while at the same time completely ridiculing and destroying it. I had the impression that he threw us under the bus, in order to build for himself on the wave of this textual failure a better preamble to the fact that the script would not yet be ready at that point.

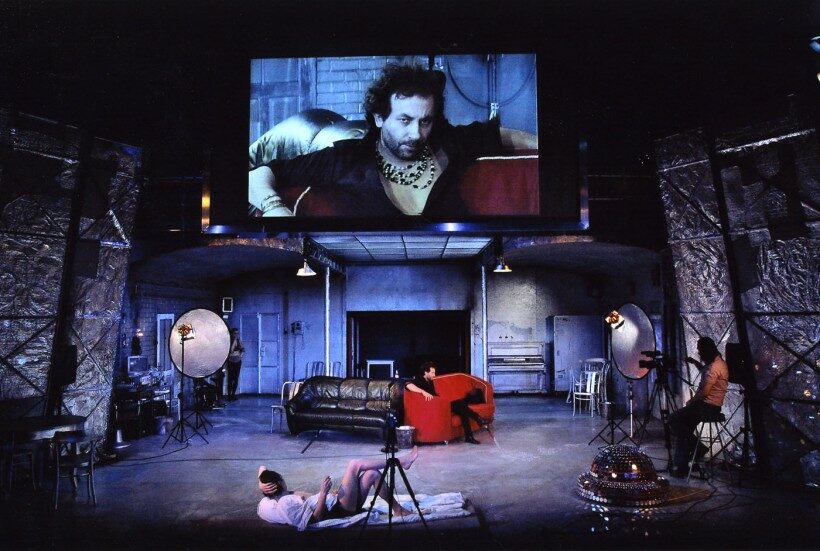

Factory 2, Krystian Lupa, dir. Krystian Lupa, premiere: 16 February 2008, Stary Theatre, Kraków, photo: Krzysztof Bieliński.

The casting process was ‘dramatic’ as well. On the one hand Lupa asked the actors to express their preference in various aspects in a letter to him, but it was clear to everyone that he was making the decisions, and could use sincere declarations of actors against their intentions since, as Warnke terms it, ‘He built up tension like at the Miss World pageant’.27 But the impression of agency the director gave the actors seems illusory. While it did happen that the wishes of actors were granted, that only happened when they were aligned with the director’s vision. Małgorzata Hajewska says: ‘I admitted that I would like to play Viva, and he replied: “It’s just as well”’.28 In a conversation I have recently had with Hajewska, the situation appears more complex; it reveals the tension between the actress and the director and the risk taken by the actors who were to disclose their ‘dream’ to Lupa. Hajewska says:

I was honest in my suggestions. I wrote that I would like to play Valerie Solanas (who shot Warhol) as well as Greta Garbo and Viva. With Solanas, once I thought about that character, I became scared. […] Do I want to duel with Lupa? […] My second suggestion was Greta Garbo. I don’t know where I found the courage to “reach out for” that ideal of mine and speak about it aloud. When the director asks you who you want to play, he induces you to reveal yourself. Would he not laugh inwardly at your suggestion?

The actors who, like Zbigniew Kaleta, were not as lucky had to accept Lupa’s decisions, even if they objected to them: ‘I chose Dylan, who didn’t make it into the show at all. […] I was sure I’d be cast as Morrissey. I really didn’t want to play him’.29

‘Playing’ a group of actors/characters also consisted in sending letters to certain individuals: ‘He’d send us e-mails that he called “cooking pots”. They contained information that was to inspire us to further improvisation and constructing our characters. He often used situations associated with me, my private affairs which he knew about,’ says Adam Nawojczyk.30 Iga Gańczarczyk argues that the ‘cooking pots’ ‘were important in building tension in the group, stirring conflict between the actors. They could contain instructions that you were not allowed to reveal to the group, as the other person would then prepare for it, arm themselves. When discussing some of the improvisations, someone would betray that they received instructions, had a theme. At that point their behavior would become more understandable.’ She also recalls Katarzyna Warnke and Tomasz Wygoda’s improvisation, which seemed cruel to her: ‘Kasia cornered Tomek with a camera. She was getting to him, mostly using her words, some ghastly attempt at a conversation, and Tomek wasn’t ready for it.’ In the journal accompanying the rehearsals, Lupa writes about explicit and implicit directions as an ‘imperative’. It is that imperative that stimulates conflict or even sadism:

For instance, that third, humiliated, eliminated, worse girl is not allowed to come out from under the table and join in as a partner. […] Is it “me” that does not allow her? Is it my idea? My need. […] The central imperative appears to be coming from somewhere outside. […] The order is too modest […] to feel secure in it, to understand it fully […] and to identify with it. […] Why should I want her to not come out from under the table? Because I want to punish her, or, for instance, I am a sadist and it brings me […] pleasure’.31

This imperative, like a thorn or a speck of dirt, provokes, causes tension and conflict, and stimulates the formation of a character that is like a ‘pearl’ growing around it. In this context Warnke’s statement that ‘Krystian bred us like silkworms or oysters, threw a seed inside us and waited for a pearl to form. He founded a personality farm’32 gains a deeper significance. Adam Nawojczyk points to yet another device employed by the director: frustrating the actors. He says:

I like improvising and it seems to me that I’m good at it. Yet none of my improvisations made it into the show. Everything I say was written by Krystian or drawn from the film Chelsea Girls. I’d get ready material and say to myself: damn, why is that? That was the case with the Pope scene. Krystian was fascinated with that scene in the film and said that we would definitely have to improvise on that subject. I was waiting for it all the time and finally I asked: “The premiere is in two weeks, perhaps we should do something with that Pope?” To which he replied: “Yes, yes, yes. We need to write down the text from the film.” I wonder why everything I say was written for me. Perhaps Krystian wanted to irritate me by not allowing me to write a scene for myself?33

I will add that by some mysterious coincidence Nawojczyk’s screen test also did not get recorded. Such a context of stage creation meant that, as Iga Gańczarczyk claims, an actor frequently entering into polemics with Lupa did not argue with the material offered him right before the premiere. At the same time, he saturated his stage presence with striking aggression. We can therefore put forward a cautious thesis that in this way Lupa forced the actor into submission, at the same time enhancing the character’s expression.

A powerful and important device introducing a feeling of jealousy, rivalry and tension between the actors while at the same time generating the need to fulfill the director’s vision and putting him in a superior position were the notes sessions following the improvisations and performances, as well as Lupa’s reactions during the performances. Ojrzyńska says: ‘Factory 2 was also happening backstage […]. In the third part of the show Lupa would sit in the wings, like Warhol or Kantor. He could be seen from the auditorium. Sometimes, if he didn’t like a scene, he would circle behind us. He also stimulated the atmosphere backstage.’ Hajewska also notes this:

When Krystian runs a notes session, you can sense a provocation in it. For instance, let’s say a performance went well. He praises us, but distinguishes one person above the others. Is that manipulation? Sure it is, because if there are eighteen of us sitting there and suddenly he speaks of one person with incredible love, just as Krystian can, but says nothing of the others, jealousy rears its head.

But it was much worse when the director was displeased: ‘The actors were performing a scene, and Lupa was very unhappy with it. During the notes session he threw a bottle that smashed on the stage, very close to the actors. From today’s perspective it’s difficult to imagine that nobody reacted at the time,’ recalls Iga Gańczarczyk.34

Can the devices employed by Krystian Lupa and described here be called manipulation? Certainly. Very intelligent and effective, at that. Interestingly, the actors confirm this opinion, while at the same time indicating that never before did they have such freedom as when working with Lupa; many of their suggestions made it into the show, and they were aware of the manipulation itself and agreed to it. Nawojczyk says, for instance: ‘I knew that he was manipulating me, but he also knew that I was aware of it. And from this distance something was born that propelled me as a character. […] Sometimes I’d get annoyed by it, but then it made me laugh and I’d think to myself: he’s so cunning, I adore him’.35 Hajewska takes a similar position: ‘Krystian wouldn’t let this cauldron stop bubbling. It was a kind of manipulation, but, in my opinion, a necessary one.’ When asked whether Lupa directed them as a group of people or stimulated tensions between the actors to generate stage tension, she replies:

I have no doubt that this was the case. We observed it and took part in it. We’d meet often, intensely […]. It was inevitable that camps would form. Our internal relations, tensions, are not unique, but rather typical for a group of people spending time together and working so intensely. There’s both rivalry and hierarchy. We were aware of that. After all, when we speak of Warhol, we first think of Krystian.

According to Hajewska, the fact that the actors were adults and could quit the collaboration eliminated the argument that they were being used. Marta Ojrzyńska also points out that she perceived any tension and rivalry at a character level, and adds: ‘It was one of my most important pieces of work, encounters, experiences. I have no doubts about it.’ Iga Gańczarczyk notes that the actors ‘very much believed in the project, even when some frustrations would occur. Lupa’s myth was very strong at the time.’ According to her, the show’s success also played an important role, making the actors feel very appreciated. And certainly it gave various of the director’s devices the marks of purpose, sense, or even necessity.

The more I investigate this process, the stronger my impression is that Lupa took advantage of the situation in which as a ‘guru’,36 a ‘great artist’,37 an ‘artificer’,38 and a ‘father figure’ (Małgorzata Hajewska’s term), he seemingly ceded a part of his power to the actors, which is the basic condition of the empowerment process, in order to shift the process of directing them onto an implicit level, decisively limiting their actual agency but highly effective in achieving his intended goal, which became clarified in the work process. If therefore we can speak of ensemble work, it was based on unequal awareness and power and on the unquestionable authority of the director. We can view Factory 2 as a peculiar laboratory in which the actors were subjected to a specific experiment. Ojrzyńska says: ‘At that time it seemed to me that the show was heavily improvised. But in fact it was all very precisely set up. Those performances work like a Swiss watch.’

Many people will probably think that posing such questions of a creative process is unfounded, and we have already gotten so used to Krystian Lupa’s work methods that we have adopted them as something obvious and necessary. One could also say that theatre is not a place for practising democracy or empowerment, and in art the end justifies the means. Such an opinion is expressed, after all, by both Potocka, who writes that ‘in the exploitation of an actor the only thing that counts is artistic pragmatism’, and ‘theatre is not assessed in terms of morality’.39 and Lupa, according to whom adopting ethical categories in reference to artistic work would lead to a simple consequence: ‘We would have to close the business down and do nothing’.40Questions about the ethical dimension of collaboration are gaining an increasingly important place in theatrical practice and research, however, also or perhaps above all in relation to the most important creators of twentieth-century Polish theatre. Interestingly, the author of a highly critical statement about the artistic practices of Jerzy Grotowski and his attitude to actors and participants of his later paratheatrical practices is none other than Krystian Lupa:

He looked at his actors a bit like a sadist pornographer, a bit like a commander who built his role in theatre on his sacramental: ‘I don’t believe it’, as that’s what he’d always say to actors. […]

After all, his shows were created as a result of enormous pressure on the actors…. He had no theatrical imagination, but rather squeezed creative energy out of the actors […].

He usurped such knowledge of human nature that it gave him the opportunity to change it. I have the impression that he compelled the action participants to joint self-deception. To certain ceremonies of the golden calf cult. […]

In my opinion, Grotowski aroused states and emotions in his actors that he did not feel himself […].41

At the same time, Lupa assesses Grotowski’s responsibility for the fate of his colleagues in a highly ambivalent manner:

Łukasz Drewniak: Was he in that case responsible for opening them to something unrecognizable and then leaving them?

Krystian Lupa: Is he indirectly responsible for their broken lives, illnesses and deaths…

ŁD: No one forced anyone to work with him. Theatre is not a prison. Is the director responsible for such matters?

KL: Yes, but saying that Grotowski destroyed his people seems unfair.42

The statement concludes with the aforementioned protest against the application of ethical categories to art. It is difficult to say, therefore, what exactly these accusations are driving at, and what position in this network of dependencies within the creative process Lupa wants to take himself. However, his argument slides toward the implied premise that while Grotowski was a false prophet, he himself is (or can be) a real one:

KL: By entering this path, he became a false prophet to an even greater degree. He usurped such knowledge of human nature that it gave him the opportunity to change it. I have the impression that he compelled the action participants to joint self-deception. To certain ceremonies of the golden calf cult.

ŁD: Harsh words, but you have also talked about yourself as a prophet…

KL: I think I can discern, or one can recognize from certain gestures, whether the artist’s message is falsified or not.43

It can therefore be concluded that Lupa does not blame Grotowski so much for his work methods as for the sense that no ‘true’ prophecy stood behind it, no sincere artistic intention.44 45 Quite a different perspective is triggered by the camera-recorded production from several years later entitled Książę [The Prince], directed by Karol Radziszewski based on a script by Dorota Sajewska (premiered on 29 July 2014 at the 14th T-Mobile New Horizons International Film Festival), in which the central place is taken by the testimony of the actress Teresa Nawrot. As Agata Adamiecka-Sitek notes, ‘Her experience of working with [Piotr] Cieślak and Grotowski relayed after many years becomes a shocking testimony of literal and symbolic violence, directed against women both in Grotowski’s theatrical practice as well as in the meanings constructed by his shows.’46

Artists and theoreticians also view increasingly carefully and critically the creative practices of Tadeusz Kantor, mainly from the acting perspective. This is exemplified by the Kantor Downtown production by Jolanta Janiczak, Joanna Krakowska, Magda Mosiewicz and Wiktor Rubin (Polski Theatre in Bydgoszcz, premiere 13 November 2015) or Katarzyna Niedurny’s interview with the Cricot 2 actor Roman Siwulak.47 A similar critical perspective has already been employed in the context of Krystian Lupa’s works. Agata Łuksza examines, for instance, the institutional, personal and gender entanglements of Lupa’s collaboration with Sandra Korzeniak on the show Persona. Marilyn(Dramatyczny Theatre in Warsaw, premiere 18 April 2009):

The vivisection of femininity and its symbol, Marilyn Monroe, performed on the body and psyche of the actress, but very risky and painful for her, was sanctioned by the high professional status of the director, who as a recognized creator of theatrical masterworks held a safe-conduct pass for stage experiments. The entire project was additionally legitimized by the place where it was carried out: the Dramatyczny Theatre in Warsaw, an institution with an artistic and non-commercial profile, at the time, under Paweł Miśkiewicz and Dorota Sajewska’s directorship, particularly open to theatrical exploration. The actress became a tool in service of art, and her dependence on the director was anchored in existing, patriarchal institutional structures.48

While in Poland similar topics are most often raised at the level of artistic or theoretical reflection, in Belgium they have become the seed of a wide-ranging, public discussion in which the aggrieved themselves rebel against the violence directed at them. I mean, of course, the open letter to Jan Fabre and Troubleyn, signed by the (former) employees as well as interns of the Troubleyn company, disclosing the oppressive nature of the director’s work methods, instances of sexual harassment, taking advantage of professional and symbolic position in building a power structure based on violence, which elicited a considerable response, also in the Polish press.49

These are just a few examples of how the belief that a ‘great artist’ is free to do almost anything is increasingly undermined, especially on the level of analysis of the relationship between directors (both male and female) and the acting ensemble, where the division of power is for many reasons very unequal. All the more so in the discussion of actors/performers, inherently creative, self-aware and committed artists who want to treat theatre as a space of their own expression too. I believe that the change in reception of Factory 2 that gradually took place during my classes is symptomatic of this direction of thinking about acting.

This article is an extended version of a paper delivered at the conference ‘Krystian Lupa: Artist and Educator’ on 6–7 December 2018 at the Stanisław Wyspiański National Academy of Theatre Arts in Kraków, and originally published in Didaskalia 150 (2019).

Translated by Karolina Sofulak

1. Beata, Guczalska, Aktorstwo polskie. Generacje [Polish Acting: Generations] (Kraków: Wydawnictwo PWST, 2014), p. 256.

2. Ibid., p. 357.

3. Anna Maria Potocka, ‘Patrzeć i czuć przez innych’ [‘Looking and Feeling through Others’], in Live Factory 2: Warhol by Lupa, ed. by B. Fekser (Kraków: MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art, 2017), pp. 41–42.

4. Maryla Zielińska, ‘Factory 3’, Polish Theatre Journal, 2018, no. 1, http://polishtheatrejournal.com/index.php/ptj/article/view/140/777, [accessed 27 April 2018].

5. Julia Kluzowicz, ‘Faktoryjka: Julia Kluzowicz in conversation with Katarzyna Warnke, Adam Nawojczyk, Zbigniew Kaleta, Krzysztof Zawadzki and Piotr Skiba’, Didaskalia 84 (2008)

6. The operative definition of this term is suggested by reflections organized around the concept of ‘empowerment’, used in both the social sciences and management: ‘In the sociological sense … the aim of empowerment activities is to achieve a state in which people gain/regain individual and collective control over their own life, place, postulates, interests, space, rights, the language in which their reality is described, including themselves, etc. Thanks to empowerment, people […] have a sense of agency/influence. Empowerment is also a method for restoring or enhancing the power and authority of people who have been deprived of it, or whose use and expression of power and authority has been systemically limited […]. At the same time, if we are talking about the empowerment process, we mean both subjective feeling and actual possibilities […]. Empowerment in management is understood as the process of including and involving employees in making decisions regarding the company/organization/project, which encompasses taking responsibility for their own actions, but also for the functioning of the structure. This increases the sense of belonging, the sense of responsibility for the relationships within the team’ (entry on ‘empowerment’ as edited by Agata Teutsch, równość.info, https://rownosc.info/dictionary/empowerment/ [accessed 6 November 2018]). The principles of empowerment developed in the field of psychiatry by those interested in this problem were in turn enumerated by Michaela Amering. The most important of them are the ability to make independent decisions, having access to hidden information and hidden opportunities, having alternatives to action, the sense that an individual has an impact on something, the ability to think critically, seeing through conditioning and rejecting it, which consists of a new definition of identity, agency, attitudes towards the authority of institutions, understanding oneself as part of a group, the sense of having competence and control, acquiring new skills, e.g. in the field of communication, correcting the perception of others in relation to one’s skills and abilities, being visible, change and development as an independently steered process, working out a positive self-image and overcoming stigmatization. See Michaela Amering, ‘Rola empowerment w psychiatrii’ [‘The Role of Empowerment in Psychiatry’], Dla nas. Czasopismo Środowisk Działających na Rzecz Chorujących Psychicznie, 2007, no. 11. http://otworzciedrzwi.org/files/dok/dla_nas_nr11_suma.pdf, [accessed 6 November 2019].

7. Translating these principles into theatre, I believe that in the field of production of a show, empowerment could mean to the actors, among other things, access to full information about the project; avoiding manipulation frequently based on the conviction that actors lack competence to undertake conscious artistic activities, and on two myths: of ‘the great artist director’ who has the right to exert control over the actors in the name of ‘art’ and the conviction that ‘great art’ requires sacrifice and suffering; influence on the shape of one’s own presence and stage expression, consistent with one’s personal views (though not necessarily expressing them); a sense of responsibility and influence on the process and effects of the work, one’s role in the project and its subsequent exploitation (understudies); collective work. I write more on this topic in ‘Między upodmiotowieniem a produkcją podmiotowości’ [‘Between Empowerment and the Production of Subjectivity’], in Ślady teatru [Traces of Theatre], ed. by D. Jarząbek-Wasyl and T. Kornaś, which will be published in 2019 by the Jagiellonian University Press.

8. In the further part of the text, if I do not give another source when quoting Małgorzata Hajewska, Marta Ojrzyńska and Iga Gańczarczyk, I will be using these authorized but unpublished conversations.

9. Kluzowicz, p. 17.

10. Shared with me by Iga Gańczarczyk

11. Shared with me by Marta Ojrzyńska

12. Kluzowicz, p. 18.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. Iga Gańczarczyk described in such a way the rehearsal atmosphere at that time.

16. Kluzowicz, p. 19.

17. The recording was included in the Factory 2 installation at the MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art in Kraków. Shared with me by Iga Gańczarczyk.

18. Krystian Lupa, ‘Dziennik Factory 2’ [‘Factory 2 Journal’], in Factory 2programme, ed. by A. Fryz-Więcek (Kraków: Stary Theatre, 2008), p. 18.

19. The recording was included in the Factory 2 installation at the MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art in Kraków.

20. Krystian Lupa, ‘My Fucking Me’, interview by Łukasz Maciejewski, Krystian Lupa – rozmowy/conversations, Notatnik Teatralny 54/55 (2009).

21. Ibid., p. 165

22. Kluzowicz, p. 17

23. See Lupa, ‘Factory 2 Journal’, p. 14.

24. Kluzowicz, p. 18.

25. Shared with me by Iga Gańczarczyk. Hajewska’s recording was included in the Factory 2 installation at the MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art in Kraków.

26. Kluzowicz, p. 23.

27. Ibid., p. 17.

28. Małgorzata Hajewska-Krzysztofik, ‘Maksimum siebie’ [‘The Maximum of Self’], interview by Hubert Michalak, Notatnik Teatralny 60/61 (2010).

29. Kluzowicz, p. 22.

30. Ibid., p. 19.

31. Lupa, ‘Factory 2 Journal’, p. 9.

32. Kluzowicz, p. 17.

33. Ibid., p. 19.

34. Similar behavior was mentioned by the actors in the course of the aforementioned meeting during the conference ‘Krystian Lupa: Artist and Educator’.

35. Kluzowicz, p. 19.

36. Zbigniew Kaleta’s term, ibid., p. 22.

37. Krzysztof Zawadzki’s term, ibid., p. 20.

38. Adam Nawojczyk’s term, ibid., p. 19.

39. Potocka, ‘Looking and Feeling through Others’, p. 39.

40. Krystian Lupa, ‘Fałszywy prorok teatru’, [‘A Fake Prophet of Theatre’], interview Łukasz Drewniak, Dziennik Teatralny 9 April (2009), http://www.dziennikteatralny.pl/artykuly/falszywy-prorok-teatru.html, [accessed 22 September 2019].

41. Ibid.

42. Ibid.

43. Ibid.

44. That the allegations made in this interview against Grotowski could also be applied to Lupa was pointed out by Marta Cabianka on e-teatr: ‘“I don’t know anyone else who would rummage in a human being with such curiosity,” says Katarzyna Figura about working with Lupa on his latest premiere, Persona, while adding that in the course of this mutual vivisection of intimate matters with the director she learned a lot of things about herself. In an interview for Dziennik Lupa states that Jerzy Grotowski “looked on his actors a bit like a sadist pornographer”, yet he does not believe that he can be held responsible for it […]. Perhaps also in Lupa’s theatre there is no more important issue to take up today’. See Marta Cabianka, ‘Odpowiedzialność demiurga’ [‘The Demiurge’s Responsibility’], e-teatr.pl, own material, 20 April 2009. http://www.e-teatr.pl/pl/artykuly/71222.html, [accessed 1 February 2019].

45. Adamiecka-Sitek, Agata, ‘Książę i kamera’ [‘The Prince and the Camera’], Didaskalia 127/128 (2015).

46. The question of Grotowski’s relations with actors has recently been taken up by the production Grotowski NonFiction, based on the concept of director Katarzyna Kalwat and visual artist Zbigniew Libera (Jan Kochanowski Theatre in Opole and Współczesny Theatre in Wrocław, premiere 8 December 2018), in which, as Katarzyna Lemańska writes: ‘Grotowski’s theatre, to simplify the matter greatly, is on one hand considered violence-based and patriarchal/anthropocentric, and on the other mystical, spiritual, religious, while at the same time being viewed as heretical and provocative’ (2019).

47. Katarzyna Niedurny, ‘Od Alaski po Patagonię’ [‘From Alaska to Patagonia’], Dwutygodnik 249 (2018), https://www.dwutygodnik.com/artykul/8069-od-alaski-po-patagonie.html, [accessed 1 February 2019].

48. Agata Łuksza, Glamour, kobiecość, widowisko. Aktorka jako obiekt pożądania[Glamour, Femininity, Spectacle: The Actress as an Object of Desire] (Warsaw: Zbigniew Raszewski Theatre Institute, 2016).

49. See texts in Didaskalia 148 (2018): ‘#metoo and Troubleyn/Jan Fabre: An open letter to Jan Fabre and Troubleyn’; ‘The right to reply: Troubleyn and Jan Fabre’s reply’; Keil 2018 and, for example, Katarzyna Tórz’s 2018 article. I am aware that drawing an analogy between the work methods of Krystian Lupa and Jan Fabre’s behavior is unacceptable. I am only referring to the trend of thinking wherein the work methods of great theatre artists are subjected to critical analysis.

Works Cited:

#metoo i Troubleyn/Jan Fabre. List otwarty do Jana Fabre’a i Troubleyn’ [‘#metoo and Troubleyn / Jan Fabre: An open letter to Jan Fabre and Troubleyn’], Didaskalia 148 (2018)

Adamiecka-Sitek, Agata, ‘Książę i kamera’ [‘The Prince and the Camera’], Didaskalia 127/128 (2015)

Amering, Michaela, ‘Rola empowerment w psychiatrii’ [‘The Role of Empowerment in Psychiatry’], Dla nas. Czasopismo Środowisk Działających na Rzecz Chorujących Psychicznie, 2007, no. 11. http://otworzciedrzwi.org/files/dok/dla_nas_nr11_suma.pdf, [accessed 6 November 2018]

Cabianka, Marta, ‘Odpowiedzialność demiurga’ [‘The Demiurge’s Responsibility’], e-teatr.pl, own material, 20 April 2009. http://www.e-teatr.pl/pl/artykuly/71222.html, [accessed 1 February 2019]

Guczalska, Beata, Aktorstwo polskie. Generacje [Polish Acting: Generations] (Kraków: Wydawnictwo PWST, 2014)

Hajewska-Krzysztofik, Małgorzata, ‘Maksimum siebie’ [‘The Maximum of Self’], interview by Hubert Michalak, Notatnik Teatralny 60/61 (2010)

Keil, Marta, ‘My też’ [‘Us too’], Didaskalia 148 (2018)

Kluzowicz, Julia, ‘Faktoryjka: Julia Kluzowicz in conversation with Katarzyna Warnke, Adam Nawojczyk, Zbigniew Kaleta, Krzysztof Zawadzki and Piotr Skiba’, Didaskalia 84 (2008)

Lemańska, Katarzyna, ‘Grotowski – co było, a nie jest, nie pisze się w rejestr?’ [Grotowski: What’s Past is Past?], Didaskalia 150 (2019)

Lupa, Krystian, ‘Dziennik Factory 2’ [‘Factory 2 Journal’], in Factory 2programme, ed. by A. Fryz-Więcek (Kraków: Stary Theatre, 2008)

___, ‘Fałszywy prorok teatru’, [‘A Fake Prophet of Theatre’], interview Łukasz Drewniak, Dziennik Teatralny 9 April (2009), http://www.dziennikteatralny.pl/artykuly/falszywy-prorok-teatru.html, [accessed 22 September 2019]

___, ‘My Fucking Me’, interview by Łukasz Maciejewski, Krystian Lupa – rozmowy/conversations, Notatnik Teatralny 54/55 (2009).

Łuksza, Agata, Glamour, kobiecość, widowisko. Aktorka jako obiekt pożądania[Glamour, Femininity, Spectacle: The Actress as an Object of Desire] (Warsaw: Zbigniew Raszewski Theatre Institute, 2016)

Niedurny, Katarzyna, ‘Od Alaski po Patagonię’ [‘From Alaska to Patagonia’], Dwutygodnik 249 (2018), https://www.dwutygodnik.com/artykul/8069-od-alaski-po-patagonie.html, [accessed 1 February 2019]

Potocka, Anna Maria, ‘Patrzeć i czuć przez innych’ [‘Looking and Feeling through Others’], in Live Factory 2: Warhol by Lupa, ed. by B. Fekser (Kraków: MOCAK Museum of Contemporary Art, 2017)

‘Prawo do odpowiedzi. Odpowiedź Troubleyn i Jana Fabre’a’ [‘The Right to Reply: Troubleyn and Jan Fabre’s Reply’], Didaskalia 148 (2018)

Teutsch, Agata, ed., ‘Empowerment’, równość.info.https://rownosc.info/dictionary/empowerment/, [accessed 6 November 2018]

Tórz, Katarzyna, ‘Bunt wojowników piękna’ [‘Rebellion of the Warriors of Beauty’], Dwutygodnik, 2018, no. 10, https://www.dwutygodnik.com/artykul/8070-bunt-wojownikow-piekna.html, [accessed 8 January 2019]

Zielińska, Maryla, ‘Factory 3’, Polish Theatre Journal, 2018, no. 1, http://polishtheatrejournal.com/index.php/ptj/article/view/140/777, [accessed 27 April 2018]

This article was originally published in Polish by Didaskalia. Theater Journal no. 150, 2019 (http://www.didaskalia.pl/). It was published in English by Polish Theatre Journal vol. 7-8, no. 1-2, 2019 (https://www.polishtheatrejournal.com/index.php/ptj/article/view/195/945) and reposted with permission.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Monika Kwaśniewska.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.