When the COVID-19 pandemic reached Brazil, I was in the city of São Paulo, covering an international theater festival, MIT-sp. On the last days of the event, we saw theaters being locked down and performances being either canceled or relocated to other performance venues. A few days after I had returned to Belo Horizonte, everything was locked down. Those had thus been my last photo shooting sessions of in-person performances in 2020. I would only get back into a theater again in July 2021.

At first, I took the chance to dedicate myself to editing the material collected at the festival, believing, as the majority of the Brazilian population did, that the mandatory quarantine would do justice to its name. A break in the activities for around 40 days so that, little by little, we would get back to our ordinary work rhythm. As time went by, we gradually realized this was very far from the harsh reality of facts.

Once I had organized MIT’s photos, I started following the first online experiences created by stage artists as theaters remained closed and other ways had to be sought. The moment was given to experiment.

But what about photography?

If, at that moment, one would question whether or not what was being presented was theater, taking into account the inexistence of in-person meetings between the artist and the audience, what can be said about stage photography? It had been coming along with theater for many decades, creating its own way of documenting and perpetuating the history of theater, and now it found itself before a major challenge. What role should it play? Should it reinvent itself into a new format or give in to the frames of its “cousin,” the video art, a primary tool to take to everyone’s screens the performing arts being produced at this new moment? It was already clear to me, as an individual, that the pandemic was putting us in all the history books yet to be written. But as a photographer, it was impossible not to hold photography accountable for documenting this period.

While some friends and colleagues started to lend both their views and equipment to record and broadcast online plays, I remained in my field – photography – and went on dealing with the issues raised by it.

On a first cut, I did not watch any recordings of in-person performances formerly presented. I may call it an intuitive cut, for there was no elaborate timely thought about it. Today, however, I think it happened because such performances were a part of an earlier moment, already documented, and I needed to think about my work with the eyes of the present moment we were all going through.

In my initial experiences, I started capturing screenshots of performances through the known method of the print screen that, in fact, did not get me anywhere, except to the feeling of being a kind of snatcher of someone else’s images. I then started to think it was necessary to get back to the primary question: what lies in the essence of stage photography? This thought led me to works featuring historical names associated with this practice in Brazil.

From the 1940s to the early 2000s

I remembered Carlos Moskovics (1916-1988) and his stills of “Vestido de Noiva” (1943) as well as other of his works from the 40s and 50s, a period in which photography was mostly done with robust cameras equipped with not very light-sensitive films. Such technical limitations of photography and Carlos’s proximity to the fine arts brought his personal language closer to cinematographic images and perhaps even closer to paintings. Photographs in which action ad movement frequently gave place to the aesthetic rigor of composition and the poses of the portrayed performers.

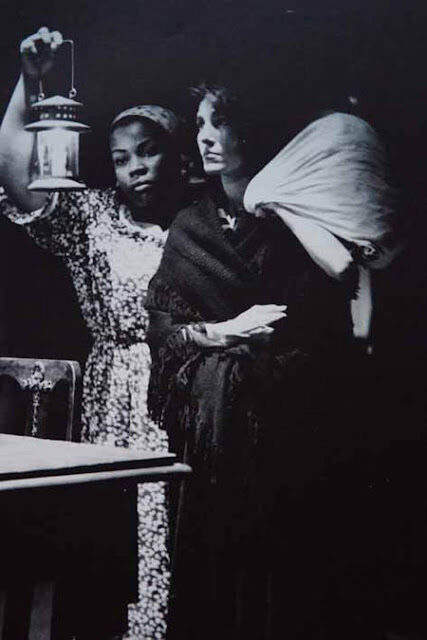

“Vestido de Noiva” [Wedding Dress] (1943). Still: Carlos Moskovics. On stage: Maria Fernanda and Stella Perry.

“Cesar and Cleopatra” (1944). Still: Carlos Moskovics. On stage: Dulcina de Moraes and cast.

Fredi Kleemann (1927-1974) brought a different approach to theater. Since his first photographic registers of TBC – Teatro Brasileiro de Comédia at the end of the 40s, it became quite common to hold dress rehearsals before the premieres so that these could be photographed by him. Such fact gave his work a kind of emotion and expressiveness that mirrored what was really happening on stage.

“Arsenic and Old Lace” (1949). Still: Fredi Kleemann. On stage: Cacilda Becker, Madalena Nicol, Milton Ribeiro, and Célia Biar.

“Paiol Velho” [Old Barn] (1951). Still: Fredi Kleemann. On stage: Zeni Pereira and Cacilda Becker.

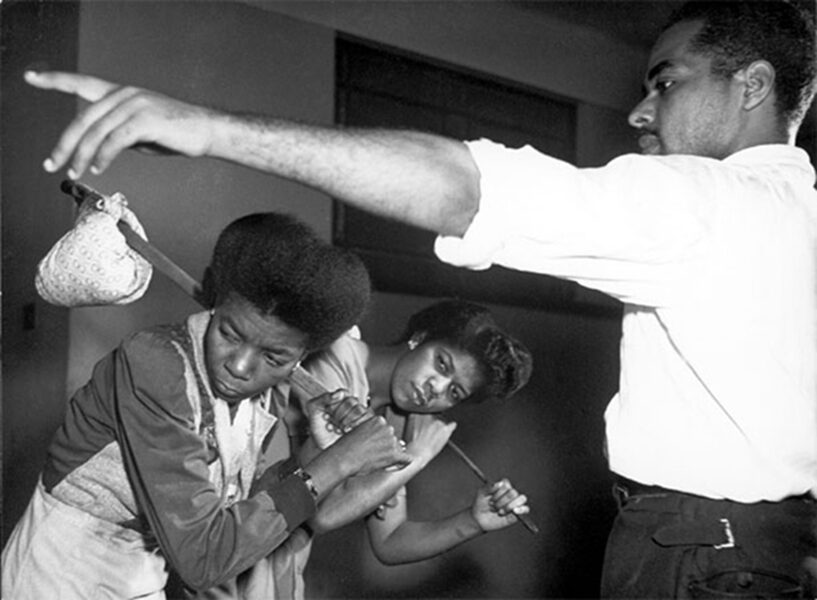

Rehearsal of “Emperor Jones” – Teatro Experimental do Negro. Still: José Medeiros. On stage: Arinda Serafim, Marina Gonçalves, and Abdias Nascimento.

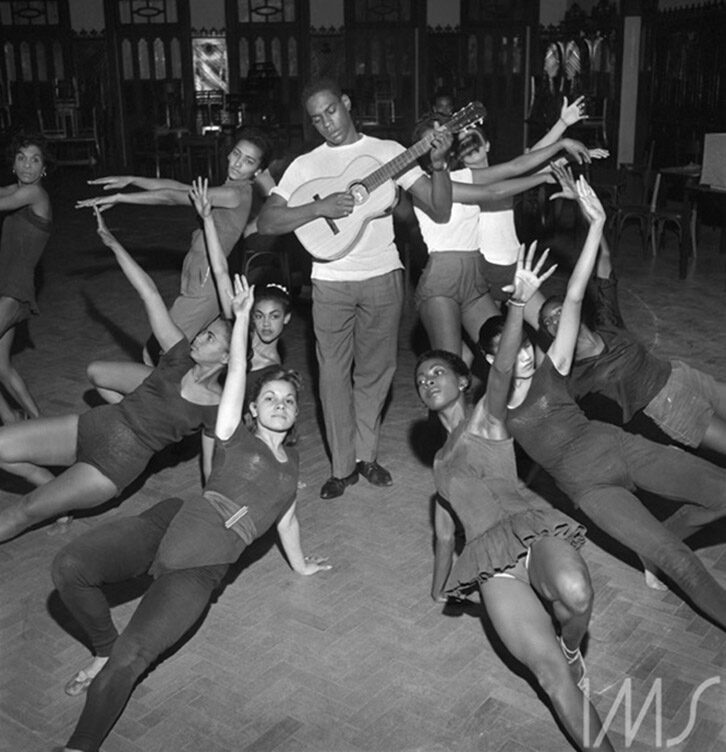

Haroldo Costa leading the cast of “Orfeu da Conceição” (1956). Still: José Medeiros. Rio de Janeiro’s Municipal Theater.

I like to say I come from a generation of stage photographers from the “last century” and that we, despite not being pioneers such as Carlos, Fredi, and José Medeiros, also faced changes and technical challenges that made us rethink our work and adjust to reality. We moved between the analogical and the digital systems. A transition that did not take place overnight, as many might think. Accustomed to shooting mostly in black and white, for in such format was printed the newspapers up to the end of the 80s, we were led to try out, as colors reached these media, the rare and technically limited higher-resolution color films. Then, with the arrival of the first digital cameras, still financially unattainable for most of us, though already found in some newsrooms, we had to invest in a hybrid process in which we would photograph in film, digitalize the images by means of special scanners, and only then send these digitalized photos to newspapers and magazines. As for me, only in 2001, I was able to acquire my first digital camera, the starting point of this new moment in my stage photography career.

“Álbum de Família” [Family Album] – Grupo Galpão (1991). Still: Guto Muniz. On stage: Wanda Fernandes, Eduardo Moreira, Beto Franco, and Rodolfo Vaz.

Today we stand before a new and major transition. Therefore, before a new and great challenge. The theater will certainly return to the stages and will once again be witnessed by the public and us, photographers, as well. However, it is to be expected (and desired) that online performances should go on taking part in our daily lives, considering that a great plethora of possibilities has been opened up and new audiences have been reached. So, what are we to expect from photography at such a moment?

Photographing online theater and dance

In November 2020, I was invited by the collective Complexo Duplo from Rio de Janeiro to cover the performances that made up the online program of the event called Complexo Sul – Plataforma de Intercâmbio Internacional which, in that year, dedicated its program to reflecting and experimenting on online lecture-performances. A perfect marriage of goals since experimenting was exactly what I had set my mind on doing at that moment.

My initial reflection showed me that my work should contribute something of its own, something video performances would not bring in their original format. Right from the start, a decision was made. It was important for me upon documenting such a historic moment that the image has the texture of the screen and of the pixels that compose it, characterizing the online broadcasting. Therefore, the screen should not only be “captured” but literally “photographed”. The next step would not be any different from what usually happened prior to in-person performances, that is, the study of the performance’s proposal and of the artist creators’ background. I had to photograph an online rehearsal of each work in order to generate the event’s advertising material.

This helped me understand them and come to the conclusion that maybe the final image should not be a single photograph, but rather a group of them. Once associated, these images would be able to create narratives that, allied to the reading of the synopses, would awaken the public interest in the works. Thus, I took the liberty to build sequences that sometimes escaped the video chronology although remaining faithful to the performances’ proposals.

“Òrò” by Tatiana Henrique (Rio de Janeiro). Complexo Sul 2020. Image created from stills by Guto Muniz.

“Se eu falo é porque você está aí” [If I speak it is because you are there] by Teatro do Concreto (Brasília). Complexo Sul 2020. Image created from stills by Guto Muniz.

“Osmarina Pernambuco não consegue esquecer” [Osmarina Pernambuco cannot forget] by Keli Freitas, with Keli Freitas, and Alex Pinhiero. (Lisbon and Rio de Janeiro) Complexo Duplo 2020. Image created from stills by Guto Muniz.

“Experimento Concreto” [Concrete Experiment] by Plataforma Àràká (Bahia) Complexo Sul 2020. Image created from stills by Guto Muniz.

“Before Falling Seek the Assistance of Your Cane” by Rabih Mroué (Lebanon). Complexo Sul 2020. Image created from stills by Guto Muniz.

This procedure was followed in registering the 10 lecture-performances created in March 2021 as a result of the creative lab “Museums, Theatre and History”, coordinated by Daniele Avila Small, who also took part in Complexo Sul’s program. This work may be seen at the following link: www.focoincena.com.br/museu-teatro-e-historia.

In this same period, I experienced online theater through the performance “Heróis: espisódio música” by Suacompanhia (SP). A “pure blood” online performance was created to be displayed in this format and that, upon diving into the universe of music, made use of several visual effects offered by the video medium. In most of the final images, I sought to create rhythms from movements, forms, and photographic sequences of different moments.

“Heróis: episódio Música” [Heroes: Episode Music] by Suacompanhia (São Paulo). Image created from stills by Guto Muniz.

“Estudos para um corpo árvore” [Studies for a Tree Body] by Thiago Cohen (Bahia). Horizontes Urbanos 2021 – Screenshot by: Guto Muniz.

“Capítulo 1: …olhar para além do que se vê… um convite a percepção…” [Chapter 1: …To Look Beyond One Can See. An Invitation to Perception…] by Andreza Aguida (São Paulo). Horizontes Urbanos 2021. Screenshot by: Guto Muniz.

Among the conclusions, that on second thought may come down to only one, is the fact that the research process about the understanding of the specificities of each performance and how the photographic technique may be better adjusted to its register remains the same. Be it in-person or online performance, it is essential. And before the new, it becomes indispensable!

Conclusions

Concerning the current reflections, I may say that a thought that takes up most of my time is the creative freedom and authorship of the images. The online performance took away from the photographer, as well as from the public, the liberty to choose the venue from which one wishes to witness the scenic work. And we, photographers, cannot even choose the optics we find the ideal for each work. All of this is imposed by one or more video cameras strategically placed at certain spots and operated by professionals responsible for directing, capturing, and editing these images. I am well aware that today I work on video frames generated by someone else’s thinking and creation. However, the discomfort involved in the “snatching of these images” was minimized by the understanding that the final result is notably different from the original, both in its visual structure and communication proposal.

If the discomfort of the mere capturing of the image has been overcome, somehow another one remains. How should we name these final images, created many times from the coming together of so many others? Should they still be called photographs? If we won’t call them photographs, how then should we call their creators? These questions may sound simple as if they were digressions or an identity crisis. They should, nevertheless, not be undervalued lest we harm rights in a process that has involved several creators since its origin.

Along with their careers, all stage photographers, from the pioneers to the current ones, have produced photographs that, much more than being important registers, have worked as creative or memory triggers. Such photographs, owing to their own essence, have always told stories that were necessarily and purposedly unfinished, able to awaken in each observer the desire to go beyond, bringing memories or building new stories in each one’s mind. This is their role as tools for advertising performances. The images shown here still play the same role.

When these performances are eventually taken out of the repertoires and stop being presented, their photographs assume a historical role. Therefore, it is paramount to document each and every process. I treasure the registering of creative processes. I frequently come upon “making of” and online performance registers. I sense with great concern the lack of images that may represent “photographically” the performances seen on our screens. Will it be that in a few years this kind of footage will be the only resource available to study these performances? Will they be accessible? Will we have to capture frames? Will these frames be able to characterize the circumstances in which those works took place?

and grown in its need for daily reinvention. What has been explored on the screens will certainly reflect on the stages. Likewise, I know my work as a photographer has already been deeply touched by my own reflections and experiments. Undoubtedly, it will never be the same.

“Piranha” by Wagner Schwartz (São Paulo) | 1, 2 na Dança 2013 International Solo and Duo Show. Image created by Guto Muniz from stage stills.

My gratitude to Daniele Avila Small, Felipe Vidal and Paulo Mattos (Complexo Sul), Paulo Azevedo (Suacompanhia), Jacqueline de Castro and Wagner Tameirão (Horizontes Urbanos) for providing such fertile ground to thinking and practice.

Published in Portuguese on Questão de Crítica. Translated for The Theater Times by Sérgio Penna.

Guto Muniz is a performance photographer and a photography teacher. His collection is available at the Foco in Cena website: http://www.focoincena.com.br/

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Guto Muniz.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.